Russia Meteor Explosion: How Powerful Was It?

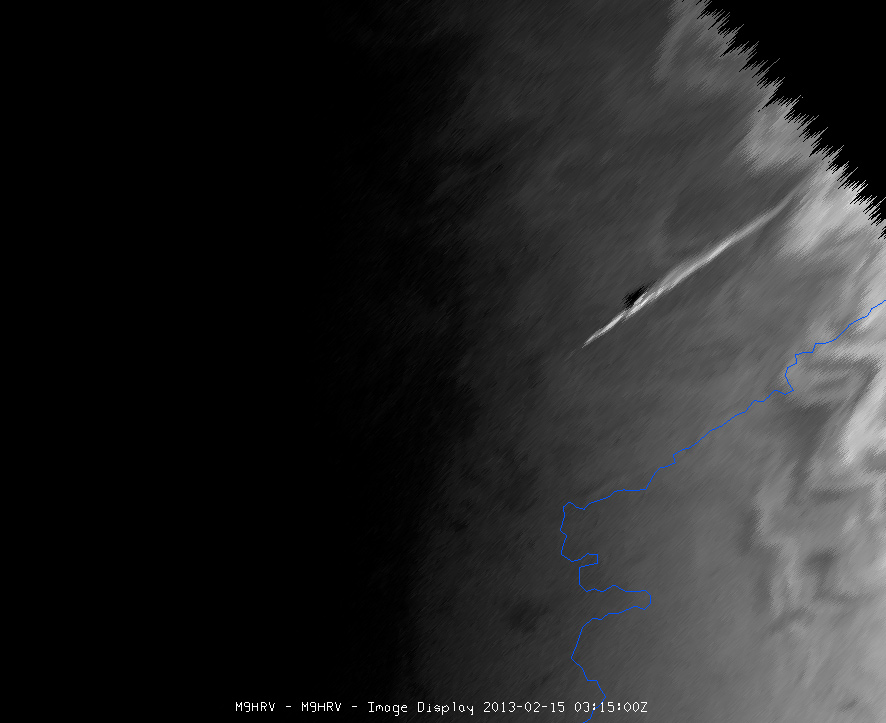

In a cosmic coincidence, a meteor exploded over Russia early Friday (Feb. 15) on the same day another hunk of space rock will whiz close by Earth.

NASA scientists say the two objects were on very different trajectories and are thus completely unrelated. But Russia has been bombarded before: In 1908, a piece of asteroid or comet exploded over Siberia. Had today's (Feb. 15) asteroid event been as large as that one, many more would be injured or killed.

"The phenomena are similar," said Mark Boslough, a physicist at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico. "It's just that this is much smaller, and it exploded much higher up."

Explosive power

Hundreds of people, possibly 1,000, are reportedly injured after today's blast in the Chelyabinsk region, about 930 miles (1,500 kilometers) east of Moscow. Most of the injuries were apparently caused by broken glass from windows that shattered in the shock wave from the fireball. [See Photos of the Russia Meteor Fireball]

Judging by the reports so far, the space rock was probably in the range of 16 feet to 33 feet (5 meters to 10 meters) in diameter, Boslough told LiveScience. That makes today's meteor a pipsqueak compared with the likely size of the 1908 event, dubbed the Tunguska event after a river near the impact site. That explosion flattened about 800 square miles (1,287 square km) of remote forest.

Both of these chunks came from the break up of asteroids and comets, which shed smaller, mostly rocky, called meteoroids that orbit the sun. Some of these fragments make their way toward Earth, burning up as they hurtle through the atmosphere, to form a meteor, or shooting star. Larger meteoroids form fireballs as they burn up and disintegrate. If a meteor survives to hit the ground, it's called a meteorite.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Tunguska object was an estimated 130 feet (40 m) in diameter, similar to the size of the unrelated asteroid, 2012 DA14, that will come about 17,200 miles (27,700 km) from Earth at 2:24 p.m. Eastern Standard Time (19:24 GMT) today. That makes a big difference in explosive potential, Boslough said.

"A 50-meter object is 1,000 times as big in terms of explosive energy than a 5-meter object," he said.

Scientists estimate that 2012 DA14 weighs about 140,000 tons, compared to 10 tons or so for the Russian object.

A boon for science

Though it may seem bizarre that the Russian explosion occurred on the same day as the 2012 DA14 flyby, events like the one over Russia are not extraordinarily rare, Boslough said. There were two similarly sized events in 2009, one over Indonesia and one in South Africa, and another in 1994 over the Marshall Islands, an island country in the northern Pacific Ocean, though all were above relatively remote spots.

"If it's the size I suspect, these things happen on average every few years to every decade or so," Boslough said.

Boslough and other researchers are currently basing their estimates of the size of Friday's meteor on damage reports and YouTube videos uploaded by eyewitnesses. But the proliferation of handheld technology is likely to provide a treasure trove of data for scientists looking to understand the event. Pinpointing the spots where videos are taken and comparing the footage will help nail down the trajectory and speed of the meteor. It's even possible that iPads or other handheld devices with accelerometers recorded the shock wave as it passed, Boslough said.

"There may be other sources of data we never had in the past," he said. "I think it's pretty exciting to think about mapping out the shock wave and getting more information about this than we've ever had from any past events."

Editor's Note: The article was updated at 1:06 p.m. EST to correct the date of the Marshall Islands meteor event. It was in 1994, not 1995.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.