Apollo Moon Rocks Challenge Lunar Water Theory

The discovery of "significant amounts" of water in moon rock samples collected by NASA's Apollo astronauts is challenging a longstanding theory about how the moon formed, scientists say.

Since the Apollo era, scientists have thought the moon came to be after a Mars-size object smashed into Earth early in the planet's history, generating a ring of debris that slowly coalesced over millions of years.

That process, scientists have said, should have flung away the water-forming element hydrogen into space.

But a new study suggests the accepted scenario is not possible given the amount of water found in moon rocks collected from the lunar surface in the early 1970s during the Apollo 15, 16 and 17 missions. By "water," the researchers don't mean liquid water, but hydroxyl, a chemical that includes the hydrogen and oxygen ingredients of water.

Those water-forming elements would have been on the moon all along, the scientist said. [Water on the Moon: The Search in Photos]

"I still think the impact scenario is the best formation scenario for the moon, but we need to reconcile the theory of hydrogen," study leader Hejiu Hui, an engineering researcher at the University of Notre Dame, told SPACE.com.

The results were published in Nature Geoscienceon Sunday (Feb. 17).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Water in moon's 'Genesis Rock'

Past studies have suggested water-forming elements came to the moon from outside sources long after the moon's crust cooled. The solar wind — a stream of particles emanating from the sun — as well as meteorites and comets were pegged as possible sources ofwater depositson the moon in recent studies.

But that explanation does not account for the amount of water found in the Apollo samples, the researchers stated in the new study.

Because they found hydroxyl deep inside each sampled rock, the scientists say they have eliminated the solar wind moon water explanation, because those particles can penetrate the surface only slightly. An impact from an asteroid or comet could push the hydrogen in further, but it would not be as pristine as the samples the researchers observed, because it would have melted from the heat of the asteroid collision.

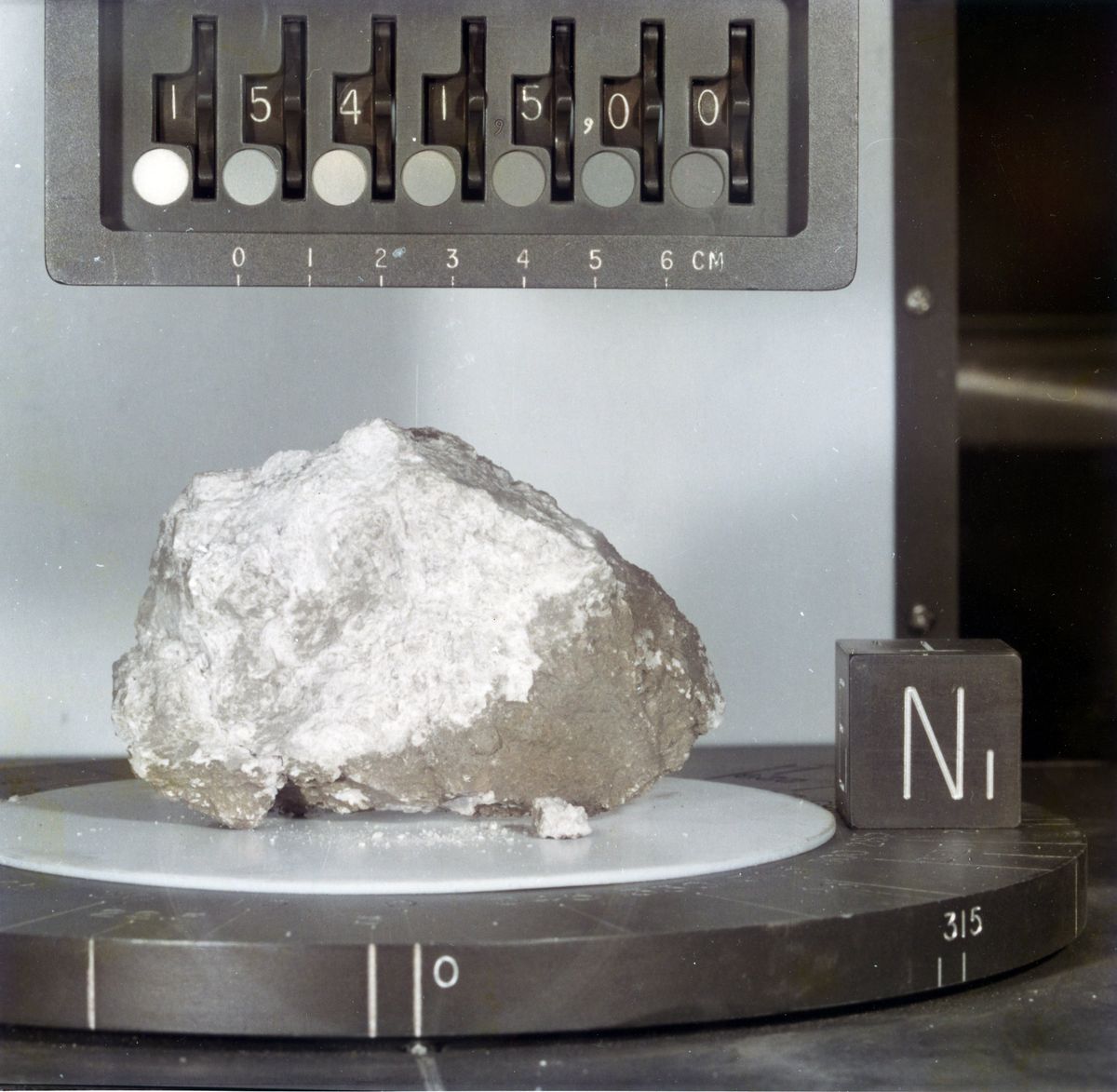

Researchers probed samples from the late Apollo missions, including the famous "Genesis Rock" that was named for its advanced age of 4.5 billion years, about the same time the moon is thought to have formed.

Using an infrared spectrometer, the researchers found water embedded in the Genesis Rock, as well as all the Apollo samples they studied. This implies that the various landing sites of Apollo 15, 16 and 17 each had water present.

Hui's research flies in the face of past analyses of Apollo rocks that found they were very dry, except for a small bit of water attributed to the rock containers leaking when they were returned to Earth.

Past instruments that analyzed these samples, however, were not very sensitive. Hui said those older spectrometers had a sensitivity of around 50 parts per million (ppm), while his instruments were able to detect water at concentrations of about 6 ppm in anorthosites and 2.7 ppm in troctolites, which are both igneous rocks found in the moon's crust.

Troctolites form in the highlands as part of the moon's highland upper crust, and anorthosites are believed to be a part of the moon's "primary" crust, which solidified around the same time as other bodies in the solar system.

Finding water in the moon's crust, the scientists say, implies that the moon's rocks could have taken longer to crystallize than previously thought. The exact amounts of water present in these rocks, however, could vary in future measurements, depending on how they are calibrated.

Past moon water finds

Hui decided to analyze the Apollo rocks again following a suite of research results in recent years suggesting the moon is much wetter than previously thought, he said.

NASA's Clementine spacecraft found evidence of water ice after scanning the surface with radar in 1996, but follow-up observations with the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico suggested the spots where it found ice were in areas with too much sun for ice to survive. Instead of ice, later researchers chalked up the observations to piles of rubble.

NASA's Lunar Prospector found possible water in 1998 at both of the moon's poles, but the instrument was only able to detect the presence of hydrogen, not other elements.

Then in 2008, new lab work on Apollo lunar samples found hydrogen in lunar volcanic glasses.

Starting in September 2009, however, three spacecraft orbiting the moon found "unambiguous evidence" of water on the lunar surface. India's Chandrayaan-1 and NASA's Cassini and Deep Impact missions detected a hydrogen-oxygen chemical link — an indication of water or hydroxyl — through wavelengths of light reflected off the moon.

These findings were believed to represent only small amounts of water. Just two months later, in November 2009, however, scientists for the Lunar CRater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) mission announced the spacecraft had found large deposits of ice at the moon's south pole.

Scientists then discovered a trove of ice in the south pole's Shackleton Crater in 2012. Based on the results, some groups say long-term human missions could live off the moon's water reserves while performing science, mining and other tasks on the moon.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.