Men and Women Both from Earth After All

Men are from Mars and women are from Venus? Think again. New research suggests that black-and-white thinking about what makes a man and what makes a woman is off-base.

In fact, while real gender differences (whether biologically based or cultural) do exist, men and women overlap psychologically more than they differ, according to a new study published in February in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. In other words, cute book titles aside, both genders are from Earth.

"Sex is not nearly as confining a category as stereotypes and even some academic studies would have us believe," study researcher Bobbi Carothers, a senior data analyst at Washington University in St. Louis, said in a statement.

Men vs. women

Carothers, who completed the research as part of her doctoral dissertation at the University of Rochester, and her colleagues are not denying that men and women often do differ from one another. Women, for example, are known to have higher levels of anxiety than men, on average, and to react to bad news with more stress. Studies also turn up gender differences in aggression, sexuality, frequency of smiling, and body image, Carothers and her colleagues wrote.

But researchers haven't spent much time examining the structure of these differences, Carothers wrote. It's possible, for example, that men and women usually fall into distinct groups. In this categorical world, knowing someone is a man would automatically tell you that he's aggressive, interested in short-term sex over long-term relationships, good at math and bad verbally. Alternatively, gender differences could occur more often on a continuum. You might know someone is a man, but it would tell you little about his skills with math. [Busted! 6 Gender Myths in the Bedroom and Beyond]

Which possibility is more likely might seem clear to anyone who has ever known a guy who can't figure out a tip to save his life. But humans tend toward categorical thinking, the researchers wrote, and gender is about as basic a category as you can get. That may explain self-help books, such as "Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus" (HarperCollins, 1992), which posit the genders as so different that they can barely communicate — at least not without the help of a guidebook.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"'Boy or girl?' is the first question parents are asked about their newborn, and sex persists through life as the most pervasive characteristic used to distinguish categories among humans," the researchers wrote.

Gender gray areas

To look at the question statistically, Carothers and her colleagues contacted researchers who had done gender-difference studies and asked for their raw data. They gathered data on 13,301 individuals who had participated in 13 different studies looking at 122 behavioral and personality factors that might differ between genders.

The researchers then crunched all the numbers to find out if differences fell into categorical patterns or on a continuum.

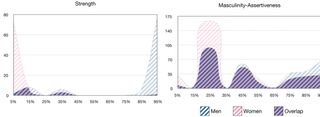

They found some categorical differences. There was little overlap between male and female physical strength, for example. Likewise, weight, height and arm circumference fell into largely distinct groups for men and women. So did activities specifically chosen as sex-stereotypical. Turns out that it's true that men aren't that crazy about scrapbooking, and not that many gals get into boxing.

But on psychological measures, gender is a gray area. Men and women fell along a continuum on such measures as interest in casual sex, frequency of thoughts about sex, and the appeal of certain traits such as virginity, looks and wealth in a mate. The same was true of attitudes toward close relationships, empathy and other interpersonal factors.

In other words, if told that a person is more than 6 feet tall, you would be pretty safe in guessing that they were a guy. If told that a person is very empathic, you'd be much harder-pressed to correctly guess their gender.

Personality traits such as extroversion and openness to new experience also fell along a continuum, as did stereotypically masculine and feminine personality traits such as caregiving, self-sacrifice and desire for justice. Interest and talent in science also fell along a continuum, despite stereotypes that men are better.

Nor did the supposed "masculine" and "feminine" traits stick together, the authors wrote. A man high in aggression is no more likely to be better at math than a man low in aggression.

The effect of gender stereotypes

The data from the studies used reaches back years, when gender roles were not as fluid as they are today, the authors wrote. That strengthens the argument for a gender continuum, they said, because gender differences show up as flexible even when gender stereotypes were stronger.

Whether gender differs on a discrete or a continual scale may seem an academic question. But how people think of the opposite sex can directly influence human relationships, said Harry Reis, a University of Rochester psychologist and a co-researcher on the study. [6 Scientific Tips for a Successful Marriage]

"When something goes wrong between partners, people often blame the other partner's gender immediately," Reis said in a statement. "Having gender stereotypes hinders people from looking at their partner as an individual. They may also discourage people from pursuing certain kinds of goals. When psychological and intellectual tendencies are seen as defining characteristics, they are more likely to be assumed to be innate and immutable. Why bother to try to change?"

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.