Volcanoes: Facts about geology's fieriest features

Discover interesting facts about volcanoes, including why and where they form and history's deadliest eruption.

The world's largest volcano: Mauna Loa, which rises 30,000 feet (9,000 meters) above the seafloor

Number of active volcanoes in the U.S.: 165

Deadliest volcanic eruption: The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, which killed up to 100,000 people

From lava fountains to towering ash clouds, volcanoes produce some of the most dramatic geological events on the planet. Volcanoes are cracks in Earth's crust that allow molten rock and hot gases to escape. According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), there are about 1,350 volcanoes worldwide that have the potential to erupt. That doesn't count undersea volcanoes, which would add another several thousand to the list.

Volcanoes are considered active if they have erupted sometime in the past 11,700 years, a time period called the Holocene epoch. If they haven't erupted during the Holocene, they are considered extinct. Sometimes people refer to volcanoes that haven't erupted in a long time as "dormant," but there's no scientific definition of that word. It could mean a volcano that erupts regularly but is currently quiet, or it could refer to a volcano that probably won't ever erupt again.

5 fast facts about volcanoes

- Volcanic ash is made of fragments of rocks, minerals and volcanic glass. These pieces are the size of a grain of sand or smaller.

- The lava that erupts at Hawaii's volcanoes comes out of the ground at about 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit (1,250 degrees Celsius) — hot enough to melt gold.

- Volcanic "bombs" are chunks of semimolten lava that fly out of a volcano and solidify as they land. They're often flung miles from the volcanic crater.

- In 1883, the explosion of the Indonesian volcano Krakatoa made the loudest sound ever recorded - 310 decibels.

- When Mount St. Helens erupted in 1980, it blew away the top 1,300 feet (400 m) of the mountain — about the height of the Empire State Building. ts can use their trunk like a snorkel in the water.

Everything you need to know about volcanoes

How do volcanoes form?

Earth's top layer, the crust, is made of cool, hardened rock. But in some places, geological processes cause parts of the crust to melt. Or the crust can crack open enough to let melted rock from the next layer of Earth, the mantle, rise to the surface.

One place this happens is at the boundaries of tectonic plates, which are the huge pieces of crust that fit together like puzzle pieces and cover the surface of the planet. At places where two tectonic plates are pulling away from each other, magma — hot, molten rock — can rise from the mantle to the surface, forming volcanoes.

Volcanoes can also form where plates crash into each other. When one tectonic plate pushes beneath another, it's called subduction. The plate diving into Earth pulls down rocks and minerals full of water. When that water-rich rock gets put under pressure by the weight of the crust pressing down on top of it, it can melt. This melting forms volcanoes.

Volcanoes can also form at hotspots, which are places where a really hot plume of rock in the mantle bubbles up, weakening the crust.

Where are volcanoes found?

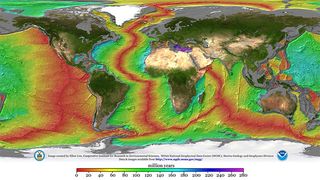

The volcanoes that form where tectonic plates are pulling apart are now seen at midocean ridges, which are places under the ocean where two pieces of crust move away from each other. Two major midocean ridges are the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which runs down the center of the Atlantic Ocean like a zipper, and the East Pacific Rise, which runs along the west coast of North America and then out to sea in the southern Pacific.

The volcanoes that form where tectonic plates are pushing together happen anywhere that ocean crust goes under ocean crust, or anywhere that ocean crust goes under the crust that makes up the continents. The main place to find these types of volcanoes is the "Ring of Fire" that circles the Pacific Ocean. There are more than 450 volcanoes in the Ring of Fire, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Volcanic hotspots, on the other hand, occur in the middle of continents. Hot mantle plumes sit in one place for long periods of time while the crust slowly creeps over them. Yellowstone National Park, the Hawaiian Islands, and American Samoa are all landscapes formed by hotspot volcanoes. Hotspots are also found in Iceland, in the Afar region of Africa, and under the ocean worldwide.

What types of volcanoes are there?

Cinder cones are simple volcanoes that form where vents, or openings, spit out ash and lava. They can be cone- or oval-shaped, usually with a bowl-like crater at their summits.

When a cinder cone erupts over and over, it can evolve into a stratovolcano. Stratovolcanoes are cone-shaped volcanoes that build up from layer after layer of lava and ash, one eruption at a time. They're also called composite volcanoes. Mount Rainier in Washington is a famous stratovolcano.

Shield volcanoes are big, broad volcanoes made up of oozy lava flows that erupt from multiple vents. Hawaii's Mauna Loa and Kilauea are both shield volcanoes. Though they don't form a classic cone shape, shield volcanoes can be massive: Mauna Loa has an estimated volume of 18,000 cubic miles (75,000 cubic kilometers). The biggest shield volcano is Tamu Massif, and it sits on a seamount east of Japan, its summit 6,500 feet (1,980 m) below the ocean surface.

One final type of volcanic system is the Large Igneous Province, a massive outpouring of lava made from rocks called basalts. These eruptions can flood millions of square miles with lava that's over a mile thick. Luckily, there are no large igneous provinces active today. But scientists think that in the past, these huge eruptions caused some of the planet's biggest mass extinctions.

How do volcanoes erupt?

The first hint that a volcano might erupt is usually a lot of tiny earthquakes. Some of these might be big enough that humans can feel them; others can be detected only by sensitive instruments. Either way, the quakes hint that magma is moving beneath the surface, pushing through breaks in the rock and causing the ground to tremble.

The ground may swell as unseen magma flows toward the surface. Often, the volcano starts belching out more volcanic gas. Sometimes, new vents open in the ground so this gas can escape. The ground may even get hot as magma warms it from below. On some snow-covered volcanoes, scientists watch for new lakes forming near volcanic vents. These snowmelt lakes can reveal hotspots of magma below.

In a non-explosive eruption, like those that happen at Hawaii's volcanoes, lava fountains or oozes from cracks in the ground. The lava in these types of volcanoes doesn't contain much dissolved gas, so it doesn't erupt with a lot of force. It's more like gooey syrup than a shaken-up soft drink.

Explosive eruptions, though, can blast huge amounts of rock and ash thousands of feet into the air. The May 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens sent ash 12 miles (19 kilometers) into the sky in the first 10 minutes of the explosion. Volcanoes like Mount St. Helens also often release pyroclastic flows, which are avalanches of hot rock, gas and ash that spill down the slopes at more than 200 mph (320 km/h). Pyroclastic flows can be as hot as 1,300 F (700 C).

Explosive eruptions might also release molten lava flows and lava bombs, which are chunks of partially melted rock that can fly for miles. Some icy volcanoes produce huge mudslides called lahars when hot rock and hot gas melt ice and snow on their slopes.

Volcano pictures

Hawaii's fire

Lava fountains from Halema'uma‘'u at the summit of Kilauea the evening of Feb. 11, 2025. Some fountains reached 200 feet (60 meters) high.

A quiet volcano

Mount St. Helens in June 2024. Spirit Lake, to the left of the mountain, became a natural laboratory for scientists to study the recovery of an ecosystem after an eruption. Although it was full of ash and had no oxygen at first, tiny creatures called phytoplankton started living in the lake again the same year, reestablishing the food web.

After the eruption

USGS geologist Don Swanson and his colleague Jim Moore examine a car buried in ash by the May 18, 1980, eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington.

The Yellowstone supervolcano

Yellowstone National Park sits on a volcanic hotspot that erupted dramatically 640,000 years ago. There's no sign that the supervolcano will erupt so catastrophically in the near future, but the park's geothermal features are a reminder of the heat beneath. Abyss Pool contains 181F (83 C) water that occasionally erupts without warning, spewing steam and hot water 100 feet (30 m) into the air.

Discover more about volcanoes

—The Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Project

—Cascades Volcanoes Observatory (USGS)

—Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park

US volcano quiz: How many can you name in 10 minutes?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.