Students Get Satellite Time: Inside the Mars Student Imaging Project

A project that puts middle and high school students in charge of an instrument on NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter received a top prize from the journal Science today (Feb. 21).

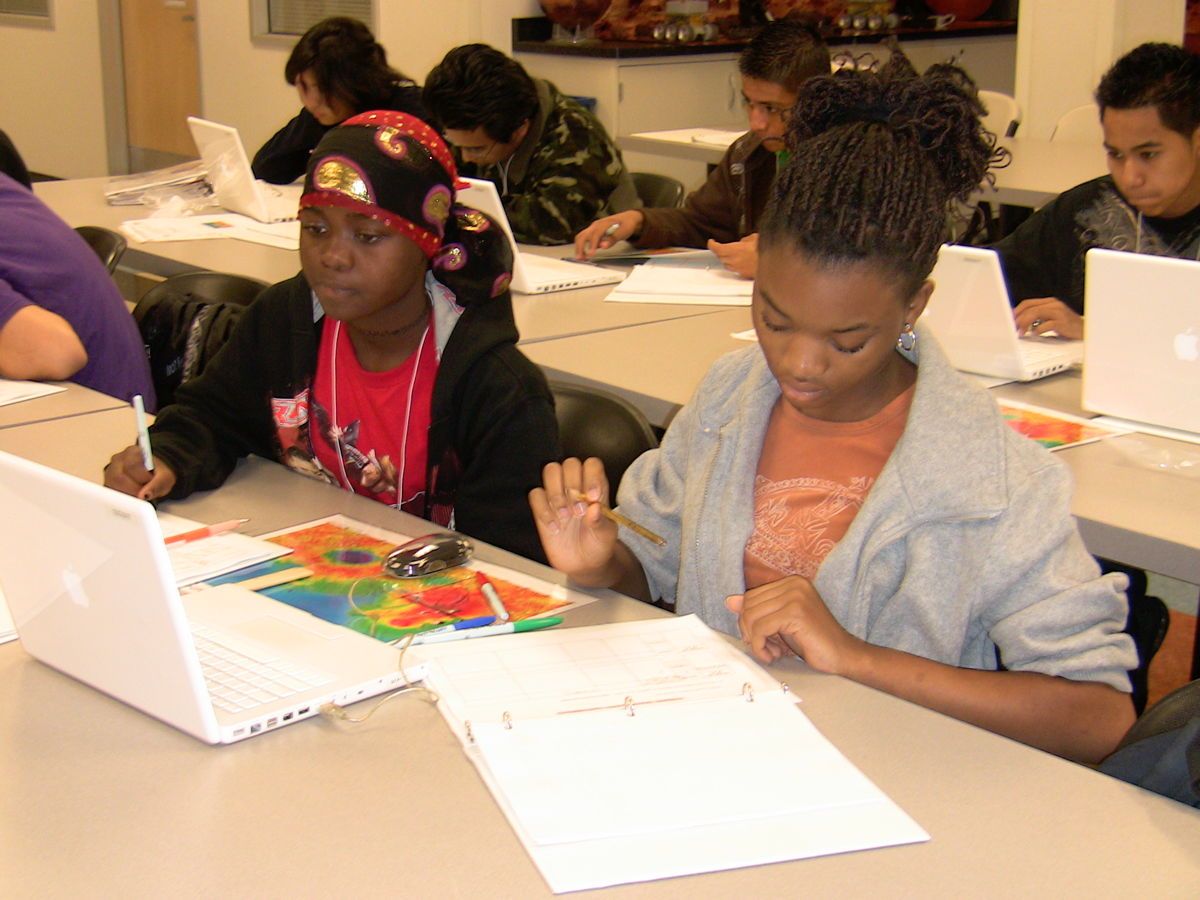

The journal recognized the Mars Student Imaging Project, which allows young scientists to request time on the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) instrument aboard the satellite after developing and proposing their own research. But the benefits go beyond learning about Mars.

"The underlying premise of what Mars Student Imaging is about is helping students to learn the process of science, the nature of science and how it works," Sheri Klug Boonstra, director of the Arizona State University Mars Education program in charge of the project, told SPACE.com.

"They're going to be able to apply that understanding in every other class they take."

Science announced today that the project is the recipient of its Prize for Inquiry-Based Instruction, which seeks to recognize programs that promote active learning, where students are engaged in collecting data through resources or experiments. [Gallery: Students Use NASA Satellite to Study Mars]

"We're very humbled by it," Boonstra said. "It's been a great honor."

A growing project

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After Odyssey launched in 2001, THEMIS principal investigator Philip Christensen, also at Arizona State University, began to think about a novel and innovative way to utilize the instrument. Christensen, a major proponent of education, met with Boonstra to determine how the camera could be used to engage people in the learning process.

"We thought, as a kid, I would have loved to participate in this kind of exploration, but it just wasn't available," Boonstra said.

They pitched the concept of adding students to the Mars team to NASA, where officials "loved it," Boonstra said.

"It's a collaboration between working scientists and education," she added.

When the Mars Student Imaging Project (MSIP) started in 2002, around 500 students were helping to beta test it. Today, more than 5,000 students a year are involved. In the last decade, more than 35,000 students in 33 states have participated, ranging from fifth-graders to undergraduate college students.

"We expect it to grow even more," Boonstra said.

While classrooms make up most groups, Boonstra emphasized that the opportunity was open to all sorts of teams. Home-schoolers, museums and after-school groups have all participated in the project. MSIP offers online training, virtual office hours and recorded seminars to adult leaders who will guide students in the program.

Studying the red planet

Participants in the project start off with a basic introduction to Mars. They become familiar with the surface of the Red Planet, and study orbital images of it. The students then develop a research question that can be tested by THEMIS, and figure out where and how to collect the appropriate data.

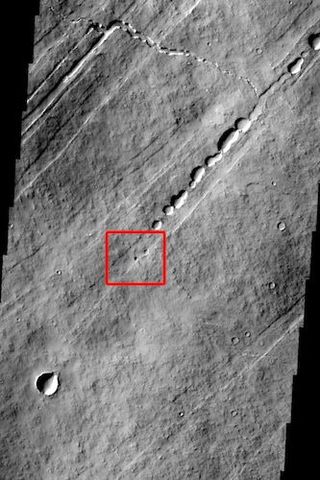

After the ASU Mars Education Program, which manages MSIP, accepts a proposal, the students use the Java Mission-planning and Analysis for Remote Sensing (JMARS) tool to study the planet's surface. Comprised of data sets of the surface taken by other researchers, JMARS is used by professional scientists as well as the student groups to take a closer look at the features in the planned target region.

The next step is in the hands of NASA, which uses Odyssey to capture the requested image of the Martian surface and sends them to the students. The teams, ranging from eight to 200 students, analyze the data they receive, creating graphs and collecting additional data. Finally, the teams present their findings to Mars scientists at Arizona State, either in person or over the Internet.

Occasionally, the student discoveries make headlines. In 2010, a group of middle school students discovered a never-before-seen Martian cave.

"These are seventh-graders that made that kind of contribution, that kind of discovery," Boonstra said. "That's where the kids get that this is real."

Other students may go on to present their findings at professional conferences or in scientific journals.

"These kids are stepping it up to be able to stand toe-to-toe with real researchers in presenting their findings at real conferences," Boonstra said.

"The nature of science"

As students follow the same route that professional scientists follow, from making proposals to analyzing data to presentations, they learn how the scientific process works.

"The kids know this is not a canned project," Boonstra said. "We don't have the answers. They're the ones with the answers at the end."

That kind of authentic science resonates with them, she said. Teachers have reported students wanting to stay later, skipping recess and going the extra mile.

"This project really does capture the imagination of these kids because it's so outside of the classroom worksheets and the regular stuff that you find in the classroom," she said.

And while Martian science may not be a large part of the curriculum, the lessons learned from the program transfer readily across science classes. A growing understanding of planetary science directly relates to Earth's formation and features.

Even more importantly, the students realize that science isn't always cut-and-dry.

"It's not a linear process," Boonstra said. "It's much more inquisitive."

She said questions often lead to more questions, and random-seeming tangents can grow into a whole new project.

"The nature of science is the nature of science," she said. "It works that way no matter what you're studying."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.