Mesa Verde: Cliff Dwellings of the Anasazi

The Mesa Verde archaeological region, located in the American Southwest, was the home of a pueblo people who, during the 13th century A.D., constructed entire villages in the sides of cliffs.

Mesa Verde is Spanish for "green table," and the people who lived there are often called the "Anasazi," a Navajo word that has been translated as "the ancient ones" or "enemy ancestors." While they did not develop a writing system, they left behind rich archaeological remains that, along with oral stories passed down through the ages, have allowed researchers to reconstruct their past.

Recently researchers found evidence that the people at Mesa Verde had sophisticated mathematical knowledge, using the golden ratio, a mathematical ratio also used at the Giza Pyramids, to help construct a Sun Temple.

The region the people of Mesa Verde lived in is defined by researchers at the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center. It encompassed almost 10,000 square miles (26,000 square km) of territory going across the states of Utah, Colorado and New Mexico, with part of the region in Colorado forming Mesa Verde National Park.

It was a tough place to make a living. "Cold, snowy winters give way to hot, dry summers, and periods of relatively abundant moisture are punctuated by sporadic — but sometimes prolonged — periods of drought," wrote a team of Crow Canyon researchers in a 2011 online article. "Living off the land has always been, and continues to be, a challenge, but one that people through the ages have met with extraordinary ingenuity and resilience."

Early history — The "Basketmakers"

The Crow Canyon researchers noted that after A.D. 500, a people whom archaeologists refer to as the "Basketmakers" (named from their finely woven baskets) moved from the peripheries of the Mesa Verde archaeological area into the center. They grew corn, squash and beans, supplementing these crops by hunting game and collecting wild plants.

In the time after they moved into the center of Mesa Verde, they developed pottery and the bow and arrow. The adoption of the bow appears to have increased their hunting proficiency, resulting in some game animals, like deer, eventually becoming overhunted and replaced with domesticated turkey.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They lived in simple pit houses with a hearth, fire hole and room for storage. Entered through the roof by way of a ladder, the house was cool in the summer and warm in the winter because it was partly underground.

These people came together in what we call "great kivas," which were also located partly underground. "These very large (more than 100 square meters, or 1,076 square feet), round structures are thought to have been used for public gatherings during which members of the community socialized, performed ceremonies, or discussed issues important to the group," the Crow Canyon researchers wrote.

Growth and first collapse

This way of life appears to have been quite successful, at least for a time. A team of researchers reported in a 2007 article in the journal American Antiquity that a portion of the Mesa Verde region, located in Colorado, more than doubled in population between roughly A.D. 700 and 850.

At this time, larger communities began to appear in Mesa Verde. These communities used a new type of above-ground structure known to archaeologists as "room blocks." Built in addition to pit houses, they contained fire hearths and places for storage. Crow Canyon archaeologists noted that these room blocks were made of adobe, stone and plant materials, with stone masonry becoming more important as time went on.

But, just as the population peaked, something happened and the people left in droves. The researchers in the American Antiquity article noted that the area of land they were studying, in Colorado, saw its population rapidly shrink between A.D. 850 and 930 to a level not much above zero. This appears to have happened across the Mesa Verde region, with the population moving south to places like Chaco Canyon in New Mexico.

Recent research suggests that a change in climate played a role in this emigration. In a 2008 article in the journal American Scientist, researchers noted that pollen remains indicate that the weather in at least part of the Mesa Verde region became colder.

"Presumably, the most productive portions of this area became cold enough in the 900s to make maize [farming] risky. Dry winters compounded this problem."

Moving back to Mesa Verde

This downturn in the climate did not last and evidence indicates that after A.D. 930 people moved back into the Mesa Verde region.

Their time at sites like Chaco Canyon, to the south, influenced them, and they brought back a type of building that archaeologists call a "great house." These buildings functioned as community centers, of sorts, that stood on high ground and contained multistory rooms.

The Crow Canyon Archaeological Center archaeologists noted that "like great kivas, great houses were public structures, probably used for community-wide ceremonies and meetings," they wrote. "In addition, great houses — with their large storage capacity — may have served as central storage and distribution facilities for both food and trade items."

A sun temple was constructed at Mesa Verde using the golden ratio and its design used a variety geometric shapes that were constructed with great precision. In addition, the people of Mesa Verde also constructed unroofed circular structures for outdoor ceremonies. Recent research reveals that a circular structure sometimes called "Mummy Lake" (which, despite its name, has no mummies) did not actually hold water but was likely used for some form of outdoor ritual.

Mesa Verde also took part in a vast trade network. "The presence of Chaco-style pottery vessels, macaw-feather sashes, and copper bells at some sites indicates that the Pueblo people of the Mesa Verde region were part of a vast trading network that included not only Chaco Canyon but much more distant locations in Mexico as well," write the Crow Canyon archaeologists.

Cliff dwellings

During the 12th century there were periods of drought and violence that drove some people to leave Mesa Verde, wrote Donna Glowacki, an anthropology professor at the University of Notre Dame, in her book "Living and Leaving: A Social History of Regional Depopulation in Thirteenth Century Mesa Verde" (University of Arizona Press, 2015). When environmental conditions stabilized in the early 13th century, the population increased in the Mesa Verde region, in some areas quite dramatically, wrote Glowacki.

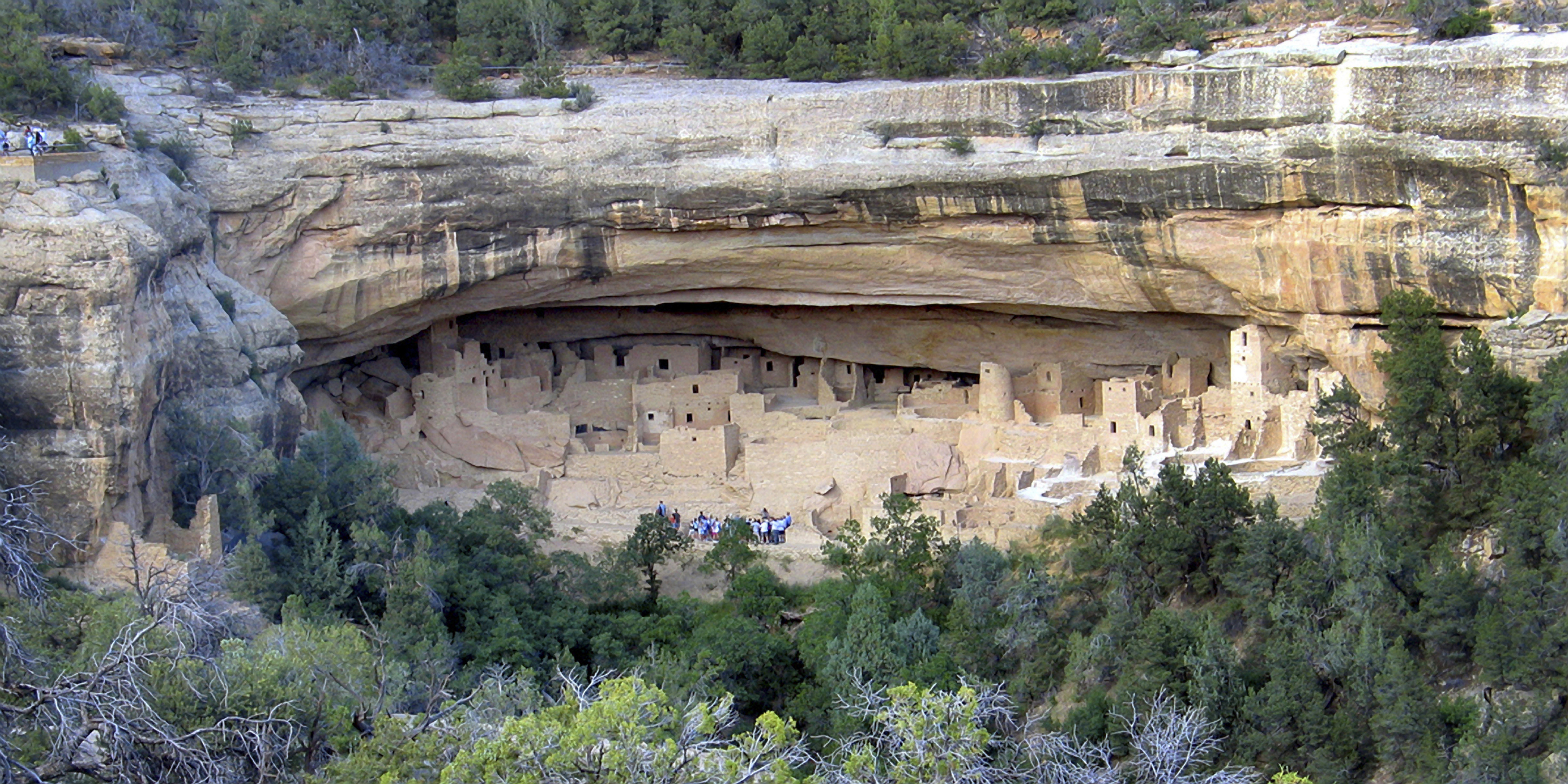

During this time of population increase, in the early 13th century, people began creating what are called "cliff dwellings," which are houses, and in some cases entire villages, built into cliff edges. The National Park Service estimates that there are about 600 of these preserved at Mesa Verde National Park. Built near springs, the naturally enclosed sites offered protection against both the elements and intruders.

"Many of the cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde are small, only one or two rooms built in alcoves or shallow caves," wrote archaeologist Larry Nordby in a chapter of the book "The Conservation of Decorated Surfaces on Earthen Architecture" (J. Paul Getty Trust, 2006). He noted that one of the largest cliff-dwelling sites is a place we call "Cliff Palace." It contains about 150 rooms and nearly two dozen kivas that were used, presumably, as a gathering place for rituals.

Cliff Palace also had many decorations that are not well preserved. "Fairly typical examples of embellishments are a panel of numerous stamped handprints above doorways and a series of zoomorphic (animal) figures painted onto plasters," Nordby writes.

Final collapse

The cliff settlements were not to last. Another population collapse occurred, this time at the end of the 13th century, leaving sites like Cliff Palace abandoned and falling into ruin. The people appear to have migrated south again to sites in Arizona and New Mexico.

In the American Scientist article, researchers noted that a mix of factors seemed to be involved in this collapse. "A combination of factors — including climate change, population growth, competition for resources and conflict — seem to have sparked the move," they wrote.

At one Mesa Verde site called "Sand Canyon," people late in the 13th century were depending more on wild plants and were eating less domesticated turkey. With the population shrinking, the site fell into ruin and "refuse was being deposited in once-important civic or ceremonial structures, such as the great kiva," the researchers wrote.

There were also signs of a battle. "Excavators found 23 complete or fairly complete human bodies, as well as scattered bones from at least 11 other individuals, indicating that at least 34 people died at or near the end of the village occupation," the researchers wrote, noting that "none of these bodies was formally buried, and at least eight exhibit direct evidence of violent death."

The people who left Sand Canyon, before the final fall, likely joined the other people of the Mesa Verde region in migrating south to new lands.

Modern-day threat

A recent study reveals that a "megadrought" even worse than the drought that wiped at Mesa Verde, may hit the American Southwest by the end of the 21st century. The effects on the people living in the American Southwest could be severe, leaving future inhabitants to grapple with water shortages amidst a hotter, more arid, environment.

Aside from leaving future inhabitants struggling for water the changing environment also poses threats to the Mesa Verde ruins. In 2014, the Union of Concerned Scientists published a report noting that Mesa Verde National Park has already suffered the loss of much of its forest due to wildfires. These wildfires, as well as flash flooding caused by the loss of vegetation, have already caused damage to the ruins at Mesa Verde and could get worse in the future.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.