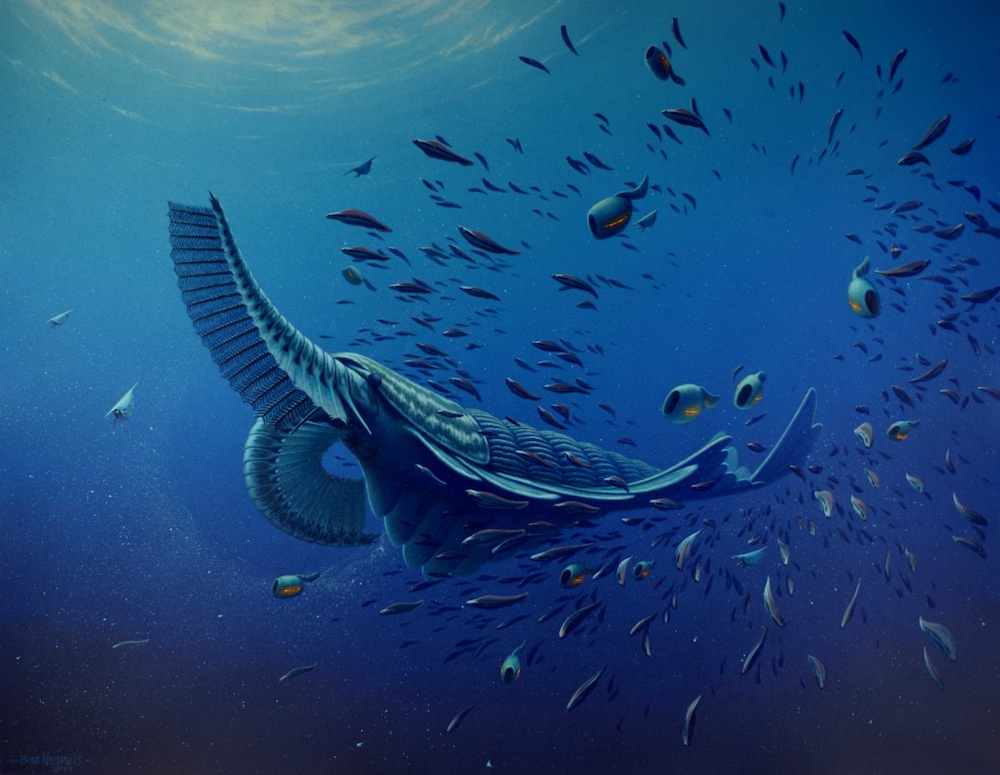

Shrimplike filter-feeder

The Cambrian explosion produced a host of bizarre and complex lifeforms, like this filter-feeding sea monster, dubbed Tamiscolaris borealis, that was unearthed in Greenland.

SpongeBob NoPants

A "nude" sponge-like animal with no organs and just one orifice that lived 500,000 years ago is offering compelling new clues about a bizarre group of ancient creatures.

Though it somewhat resembles a sponge, the newcomer — now called Allonnia nuda — belonged to the now-extinct chancelloriids. Like sponges, they lived attached to the ocean bottom, and their bodies were generally covered with spines. However, this newfound species of chancelloriid was "naked," with spines that were much smaller than is typical for the group.

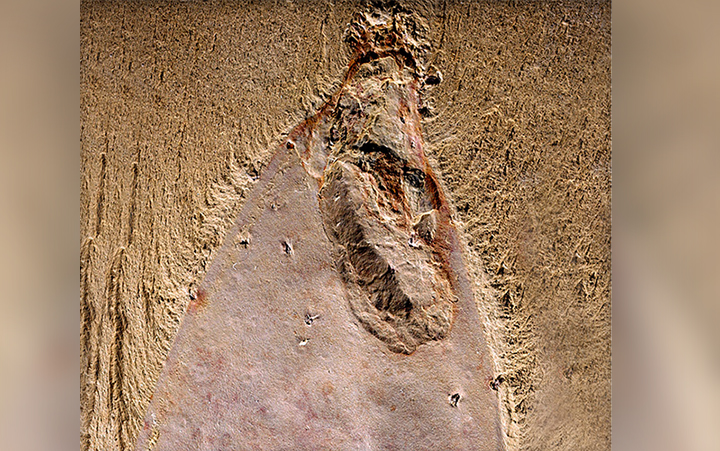

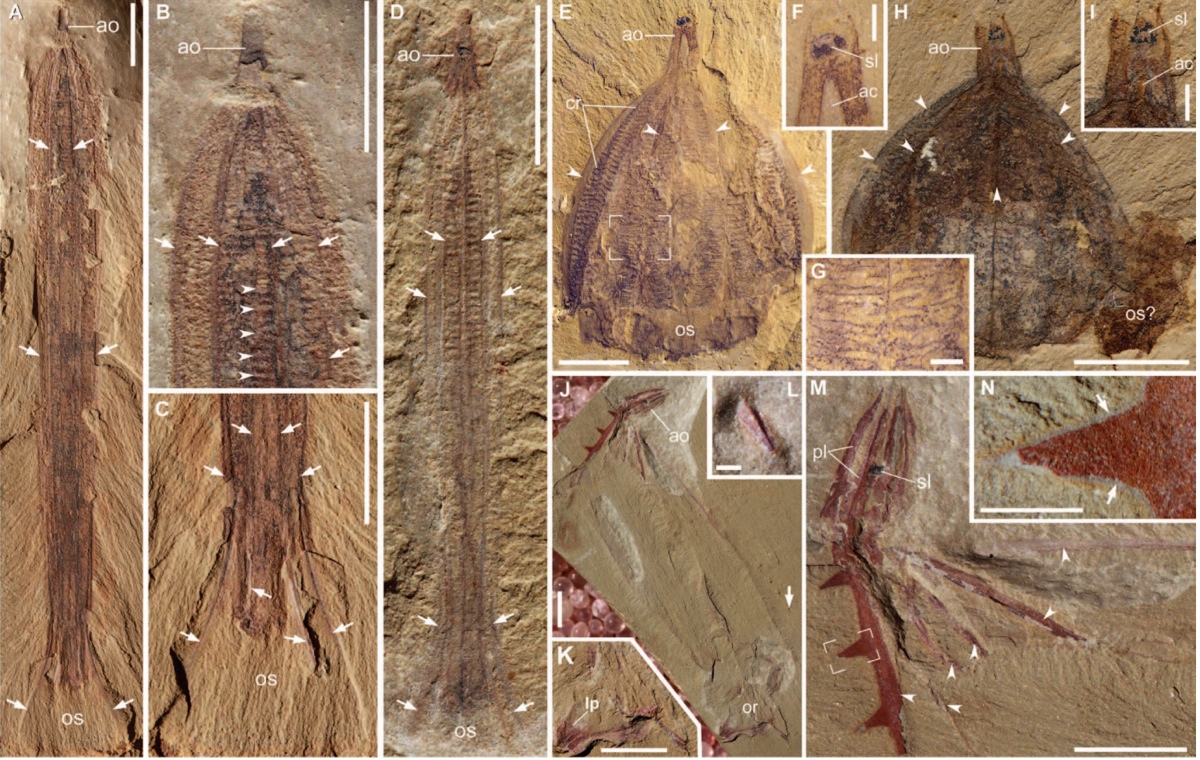

Are you jelly?

Scientists had assumed that comb jellies that lived during the Cambrian period were likely just as much of blobs as today's ctenophores, or members of the phylum Ctenophora. But new evidence from the fossil-rich site Chengjiang, in southwestern China, suggests otherwise. Here the fossil imprints of some of the comb jellies, which lived about 520 million years ago and showed the telltale cilia or hairlike structures on their bodies. The imprints belong to: Thaumactena ensis (A to D), Galeactena hemispherica (E to I), and Batofasciculus ramificans (J to N).

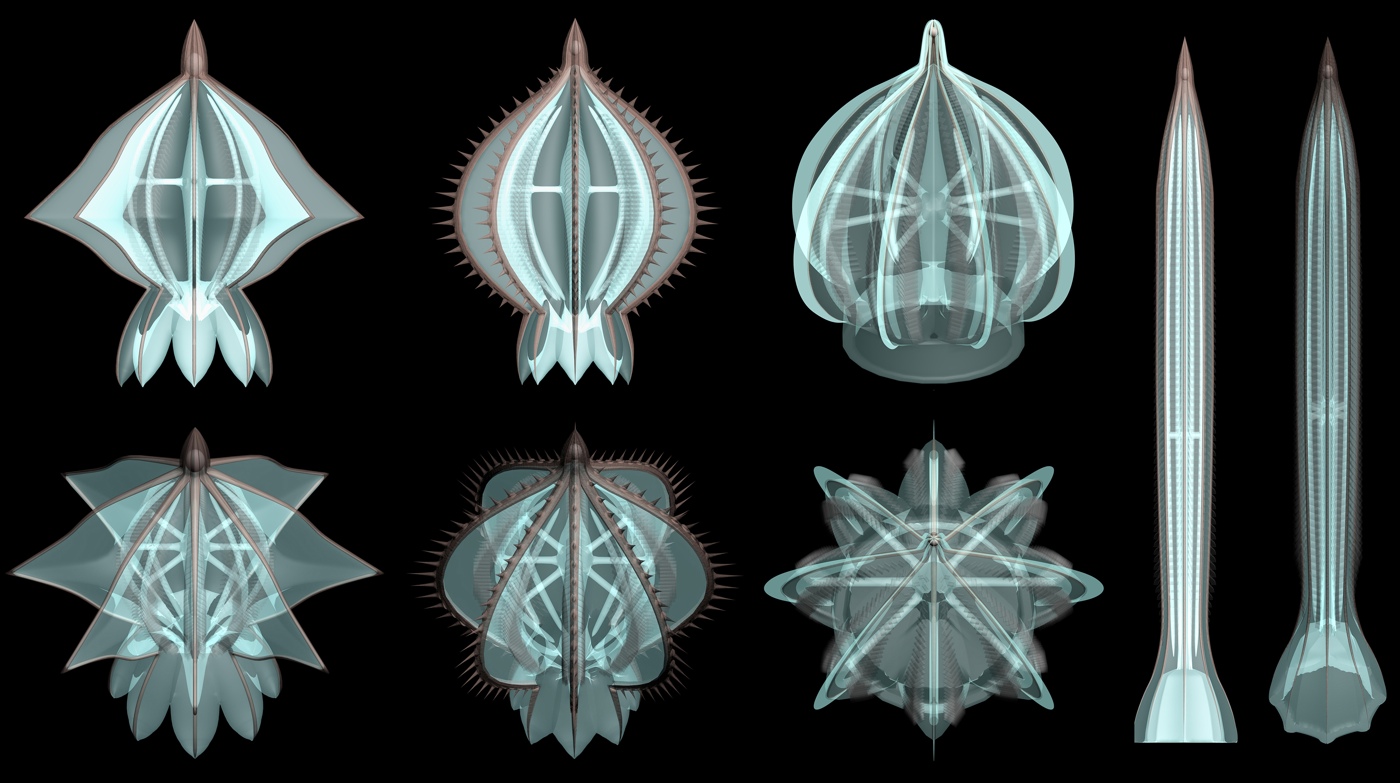

Delicate "ornaments"

The comb jellies, which are not true jellyfish and did not have stinging cells nor did they sport tentacles, were protected with hard, spiny skeletons. The little creatures may have resembled Christmas ornaments, as shown in this illustration. The research, which you can read more about in the full news article, was detailed on July 10, 2015, in the journal Science Advances.

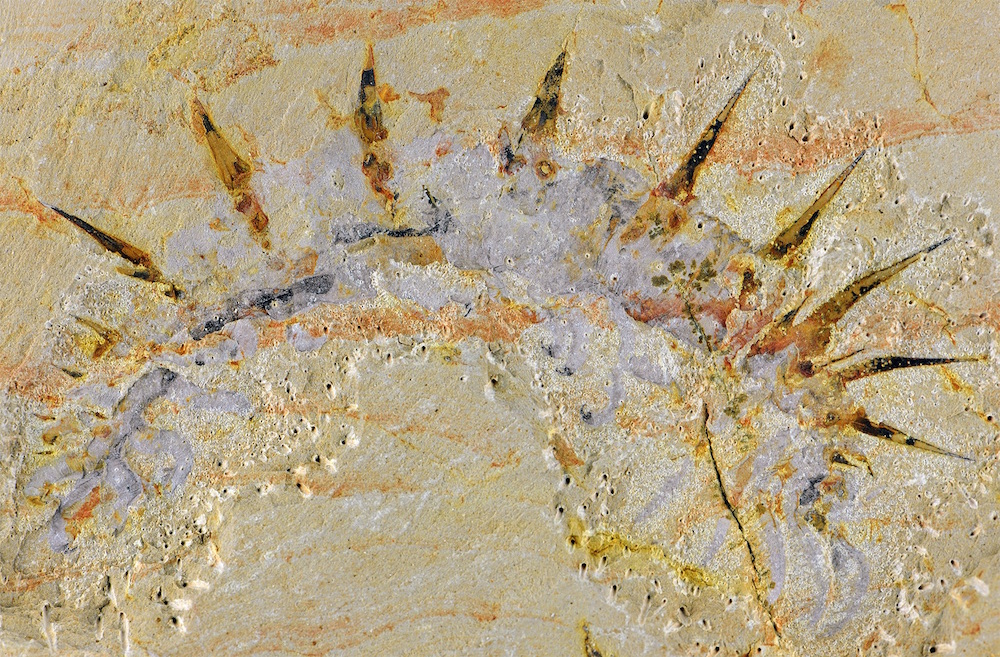

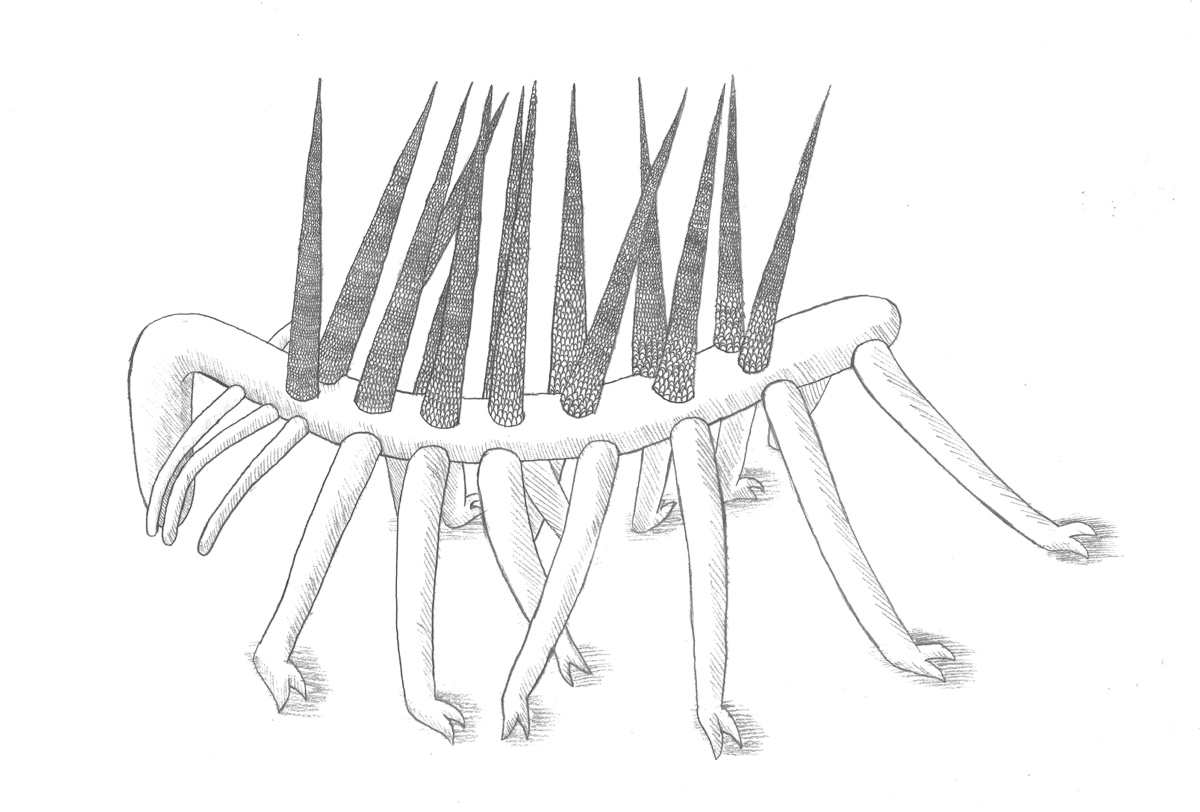

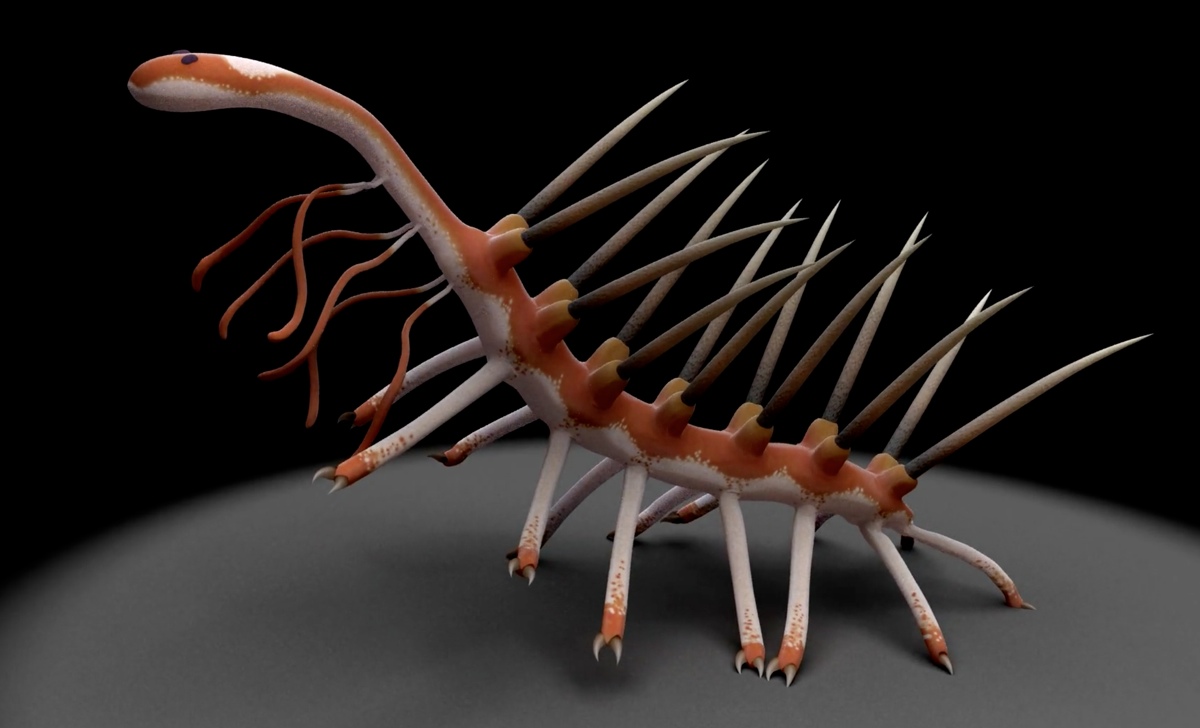

Spiky Worm

A "super-armored" worm fossil discovered in what is now southern China was rather leggy. Called Collinsium ciliosum, or Hairy Collins' Monster (after paleontologist Desmond Collins who discovered a fossil in this family in Canada in the 1980s), the creature would've sported 30 legs — 18 of which were tipped with claws to anchor the animal to penetrable surfaces and 12 feathery limbs would have waved back and forth in order to catch nutrients in the water.

Feathery limbs

Collinsium ciliosum was one the world's first armored animals, the researchers said. It used its spiky covering to protect itself from predators some 518 million years ago during the Cambrian explosion, when an array of diverse creatures of all shapes burst onto Earth starting about 540 million years ago. [Read the full story on the Cambrian worm]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fossilized remains

Researchers found 29 fossils of Collinsium ciliosum, a wormlike animal with legs, in the early Cambrian Xiaoshiba biota of China.

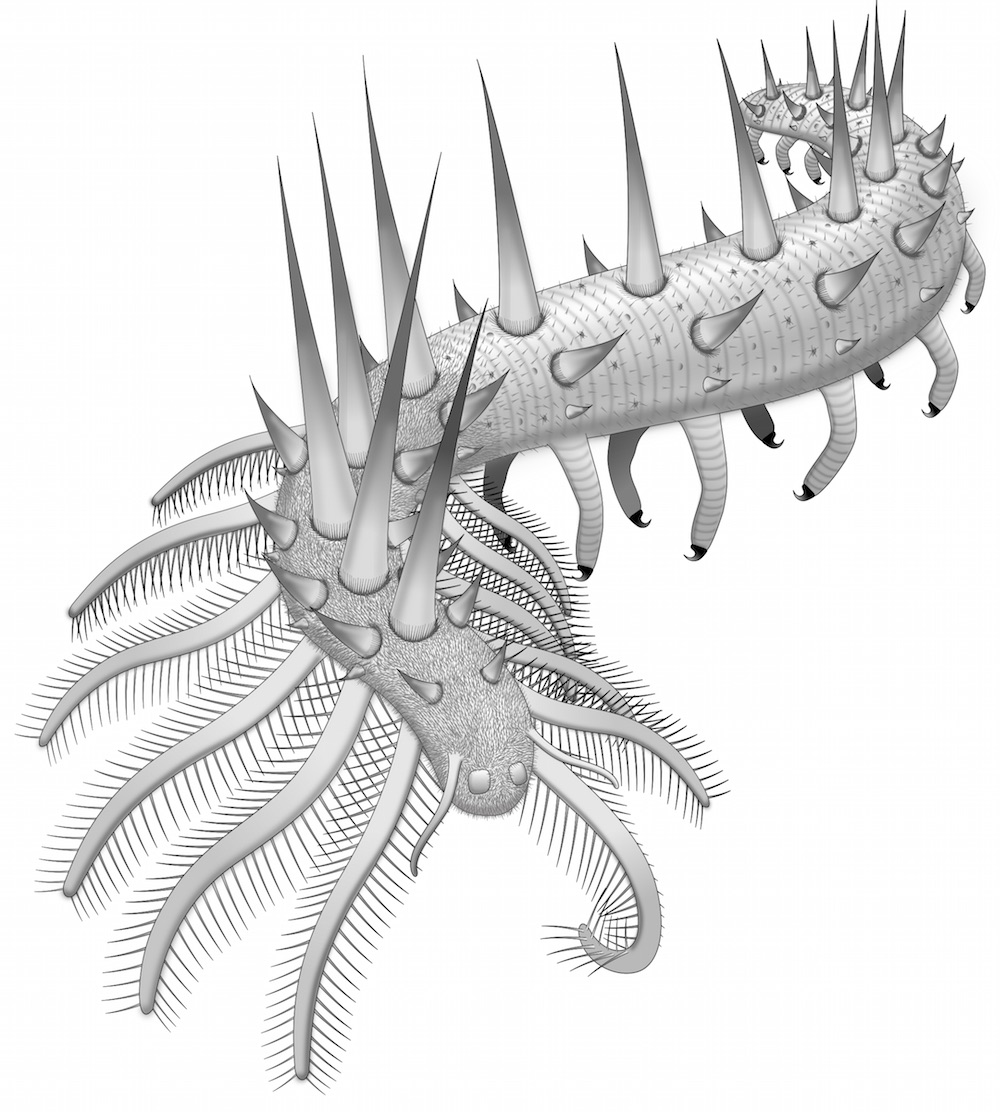

Tentacles and spikes

The fossil of a 505-million-year-old worm, now dubbed Hallucigenia sparsa, was discovered in the 1970s. At the time researchers thought its head was its tail and its legs were spines. Now in addition to righting its head and backside, scientists have found the bizarre creature is the ancestor of today's velvet worms, a group that includes sluglike animals with centipede-type legs.

Worm Fossil

The odd worm Hallucigenia sparsa gets its moniker from the word "hallucination," due to the animal's bizarre body — its head looks like its tail, it sports multiple leg pairs and strange back spines. The 1.3-inch-long (35 millimeters) worm lived on the seafloor during the Cambrian explosion.

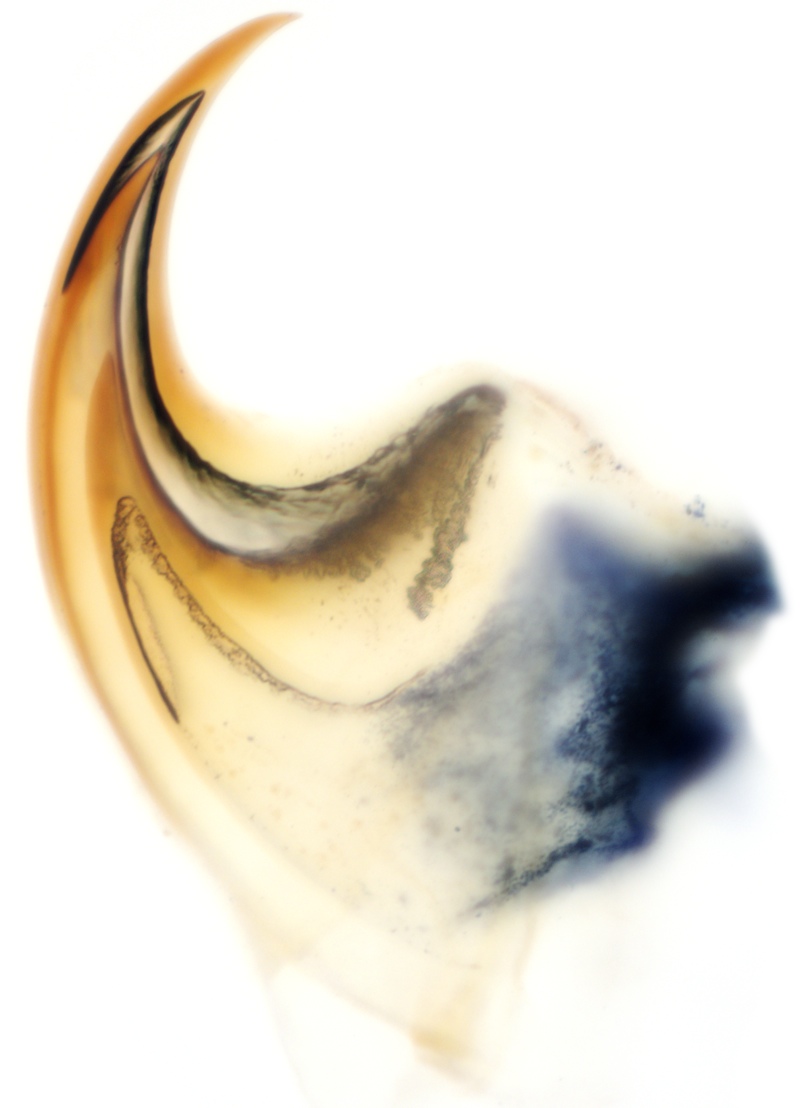

Velvet worm claw

The ancient worm had a row of spines along its back and seven or eight pairs of clawed legs. It was these leg claws that revealed the worm's family relationships. Its claws are made up of a fingernail-like material that was stacked like cups; its structure matched that found in the modified chewing claws (shown here) of modern-day velvet worms.

Hallucigenia Worm Illustration

The Hallucigenia sparsa worm was uncovered in Canada's Burgess Shale, one of the world's richest fossil sites. The ancient creature, which lived during the Cambrian period some 508 million years ago, had a 0.6-inch-long (15 millimeters) wormy body covered in spines on top and 10 pairs of spindly legs down below. And because of the animal's odd body plan and specimens available, only recently were researchers able to decipher where its face was. Turns out, it has a doozy of a mouth: a circular opening lined with teeth. The inside of its mouth and throat were also lined with teeth pointed toward the gut.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.