Freaky Fungi Glow in the Dark

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Late in the afternoon on a new moon day, we gear up: hiking boots, long pants, long-sleeved shirts, belts with knives and GPS units attached, hats with headlamps, and backpacks filled with water, snacks and plastic collecting boxes. Our expedition of nine members climbs into a 4x4 and drives 30 minutes over dirt roads into the jungle. Arriving at the trailhead near dusk, our local guide (we call him the human GPS) leads us on a six kilometer hike deep into the heart of the forest.

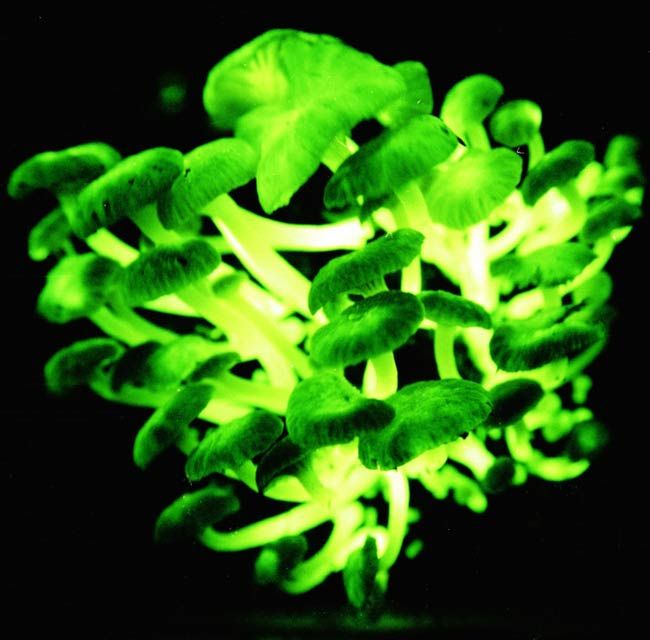

We are mycologists in search of bioluminescent mushrooms, fungi that emit light 24 hours per day but are best observed at night.

Our collecting site is a special place, one of the few remaining remnants of old growth Atlantic Forest habitat in southern Brazil. At night this forest is filled with the sounds of thousands of species of buzzing and clicking insects, creeping necrotic spiders, scurrying small mammals, rustling venomous snakes and deadly, silent jaguar. A wondrous place to behold even if we can no longer see it!

Stars at our feet

Nocturnal collecting as a pack of nine, we do stick close together – but less out of a fear of jaguar that prefer solitary prey than out of fear of getting lost!

By the time we stop hiking, it is so dark that I cannot even see my hand in front of my face. After using our headlamps to guide our way to the site, we turn them off and stumble through the darkness looking for tiny points of yellowish green light, what we hope will be luminescent mushrooms.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Soon, looking down appears as if we are looking up into a star-filled sky. We see dozens of what look like fireflies, except they don't blink off and they don't move. They turn out to be very small mushroom caps belonging to a new species that we named Mycena asterina (tiny stars).

Further into the forest we encounter a moss-covered Eugenia tree aglow with mushrooms of Gerronema viridilucens, another new species. And next to it on a fallen log is a luminescent Mycena fera. In total, this night we discover 8 different species of luminescent mushrooms, more than is known from any single site anywhere in the world.

How and why?

There are about 85,000 species in the Fungi Kingdom, of which around 9,000 are mushroom-forming species belonging to a lineage called the Agaricales (Basidiomycota, Agaricomycetidae). The focus of our NSF-funded research is in documenting the diversity of Agaricales in understudied tropical forests and in studying the evolutionary relationships amongst them.

One component of our research is to understand more about bioluminescent fungi. Interestingly, only 65 species in the entire K. Fungi are known to be luminescent. Cassius Stevani Institute of Chemistry, University of Sao Paulo also contributed to the research.

Questions that we are trying to answer include: Why are there so few luminescent fungi? What is the mechanism of luminescence? When and how many times did luminescence evolve in the fungi? Why do they glow?

Here is what we know so far: All 65 known luminescent species are mushrooms that form thin-walled white spores for dispersal, and all are white rot fungi capable of digesting both the cellulose and lignin in plant debris. The greatest diversity occurs in the tropics, although a few species grow in temperate habitats. They glow constantly, emitting a yellowish green light at a wavelength of 520-530 nanometers. Not all parts of the mushroom glow – in some species it is only the cap or the gills that glow, in others, only the stem. In some species the mushrooms do not glow at all but the fine, thread-like filaments (called mycelium)—from which the mushrooms develop—glow brightly.

Our Brazilian host, Cassius Stevani, is the chemist on the project and together we are studying the mechanism of bioluminescence. It is a luciferin-luciferase mediated reaction that emits light when water and oxygen are present. It is similar to but different from that functioning in luminescent bacteria, dinoflagellates and animals. Currently, the exact compounds that serve as substrate (luciferin) and enzyme (luciferase) are unknown, but we are close to characterizing them.

A few answers

In my lab, post-doctoral fellow Brian Perry has been obtaining DNA sequences from a number of genes from as many of the 65 luminescent species as possible to address the evolution of luminescence in fungi. We know that there are four distinct lineages of mushrooms that glow. Commonly known glowing fungi from North America like the Jack-o-Lantern Mushroom (Omphalotus spp.) and the Honey Mushroom (Armillaria spp.) belong to two different lineages.

The most diverse of the four lineages are the mycenoid fungi (Mycena and allies) with 46 of the 65 known species (70 percent). All eight species we found at the single site in Brasil belong to this group. What is most exciting is when we look at the relationships of all 500 mycenoid fungi and see that the 46 luminescent species belong to 16 different lineages.

Does that mean that the ability to emit light evolved 16 different times? Not necessarily. Our data suggest a single, early origin of luminescence in the fungi with multiple losses of the ability to emit light.

Why do they glow? Data suggest that some glow to attract nocturnal animals to aid in spore dispersal. This is especially adaptive in closed-canopy forests where wind dispersal in hindered. Others glow to attract the predators of insects that eat the mushrooms…befriend the enemy of your enemy! And some glow for unexplained reasons. We are trying to find out why.

- Top 10 New Species

Editor's Note: This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. See the Behind the Scenes Archive.