The Bittersweet Truth About How Taste Works

Scientists have created mice that can't taste sweet, bitter or savory flavors, revealing how these tastes are processed in the brain.

The ability to taste these flavors relies on the passage of signaling molecules from taste bud cells to neurons, but exactly how this happened was unknown. Scientists have now discovered the protein channel that releases these molecules, triggering nerves that tell the brain what is being tasted.

Mice that don't have this channel lack the ability to taste anything sweet, bitter or umami (the flavor of MSG), researchers report today (Mar. 6) in the journal Nature.

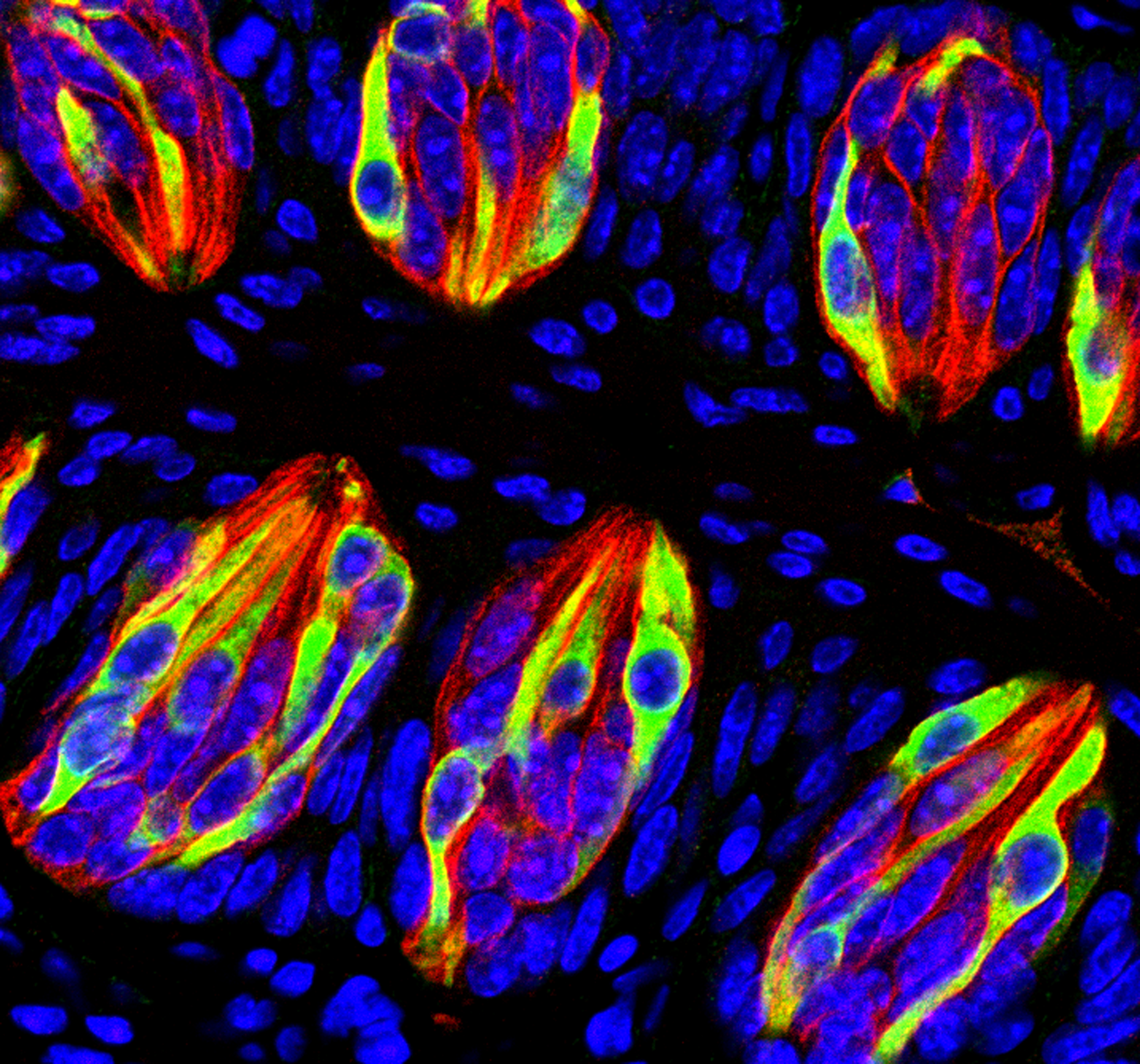

Taste buds have cells that detect sweet, bitter and umami flavors. The cells communicate these tastes to the brain by releasing a signaling molecule called ATP. Normally, brain cells communicate by special junctions called synapses, but these taste cells don't have them. [The 7 Other Flavors Humans May Taste]

"The question was, how does ATP get out to the cells of the nerve fibers to taste something sweet, bitter or umami?" study co-author J. Kevin Foskett, a neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania, told LiveScience.

Foskett and his colleaguesfound that an ion channel on the surfaces of cells called CALHM1 had a giant pore that could allow large molecules to pass through.

After a report came out suggesting CALHM1 was present in taste cells, Foskett wondered if this channel might be the missing piece that allowed sweet, bitter and umami tastes to send signals to the brain. First, the researchers tested whether ATP could fit through the channel, and found that it could. Next, they bred mice that were genetically engineered to lack the channel. When those mice were given a taste test, they could not taste anything sweet, bitter or umami.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"That was a eureka moment for us," Foskett said. "This ion channel is absolutely essential for releasing the ATP. If you don't have that channel, you can't taste sweet, bitter or umami."

The finding bolsters scientists' understanding of ATP's role in taste. "It's certainly an important piece of the puzzle," neuroscientist Sue Kinnamon of the University of Colorado, Denver School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study, told LiveScience. But Kinnamon is not convinced the new channel is the only player involved. The study's authors don't rule out other mechanisms.

The molecule ATP has important signaling roles throughout the body, not just in taste cells. The findings of this study could be extended to explain how other kinds of cells release ATP, too, Foskett said.

While the research is in its early stages, potential applications include developing drugs that interact with the channel to modify taste. For example, it might be possible to create a drug that would make taste cells more sensitive to sweet things, so a person could get the same sensation from eating less sugar. Another possibility would be blocking the channel to prevent the bad taste of medicine.

Follow Tanya Lewis @tanyalewis314. Follow us @livescience, Facebook or Google+. This article was first published on LiveScience.com.