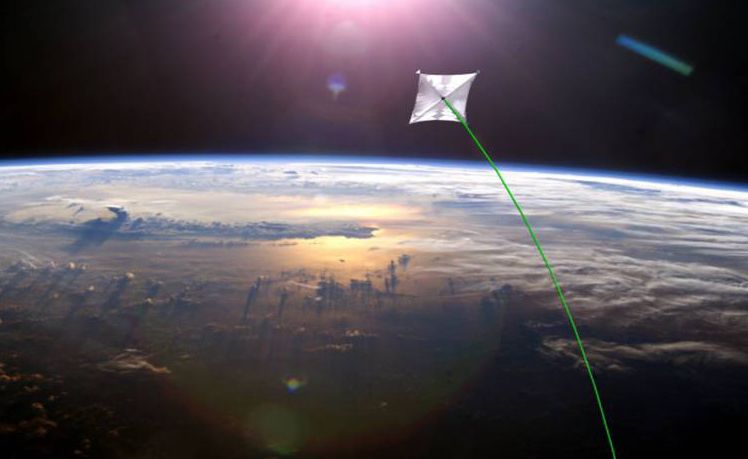

The first-ever interstellar probe may cruise through space like a boat through the ocean, propelled by super-focused light beamed onto a sail the size of Texas.

Solar sailing is perhaps humanity's best bet for reaching star systems beyond our own in the foreseeable future, some scientists say, though they caution that the first robotic interstellar flight is not exactly around the corner.

"I think it's 300 to 500 years [away], personally," said Les Johnson, deputy manager of the Advanced Concepts Office at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. "I think before we ever really undertake sending something to another star, we will probably have to be masters of our own solar system."

The vastness of space

Humanity will need to employ new propulsion technology if it hopes to launch spacecraft to other stars, because the distances involved are just too huge for traditional chemical rockets to handle. [Gallery: Visions of Interstellar Flight]

For example, the closest star system to our own is the three-star Alpha Centauri, which lies 4.3 light-years away, or more than 25 trillion miles (40 trillion kilometers). It would take a traditionally powered spacecraft about 40,000 years to reach Alpha Centauri if it blasted off today, scientists say.

Engineers are currently researching a number of different alternative-propulsion technologies, including space-bending "warp drives" and engines that harness the power of matter-antimatter reactions. But Johnson thinks the most attractive options at the moment are nuclear fusion drives and gigantic solar sails.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A fusion-powered probe is a long way off, since researchers are still trying to figure out how to build fusion reactors here on Earth that produce more energy than they take in.

"Not only do we have to solve that problem, but we've got to get a lot more out than we put in, and we've got to miniaturize it all dramatically so you can even consider launching it on a spacecraft," Johnson told SPACE.com.

Solar sailing has its own mix of promise and problems, which researchers are still trying to work through.

A light breeze

Solar sails take advantage of the curious fact that light particles, called photons, have momentum even though they possess no rest mass.

When photons hit the sail's reflective surface, they impart their momentum to the sail and the spacecraft, providing a slight push. The effect builds up over time, potentially accelerating a sail-equipped probe to tremendous speeds without the need for propellant. [Photos: Solar Sail Evolution for Space Travel]

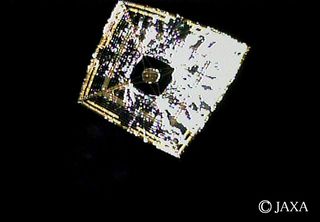

The technology has already been tested in space, with Japan's Ikaros probe deploying a 46-foot-wide (14 meters) sail in June 2010 and NASA launching an even smaller craft called NanoSail-D five months later.

These demonstrators may be first steps toward an interstellar mission, but they're halting and tiny ones. A solar sail would have to be far bigger to capture enough photons to reach another star system within a reasonable time frame — a few centuries, say.

"The physics tells us it's going to be the size of Texas," Johnson said.

The sail material would also need to be much thinner than a human hair, posing serious manufacturing, handling and deployment challenges, he added.

Beaming energy from afar

A spacecraft on an interstellar journey would ideally deploy its enormous sail relatively close to the sun — perhaps near the orbit of Mercury — to get the biggest photon push possible at the outset, Johnson said.

That push will drop off as the probe gets farther and farther from the sun, of course. So humanity will have to pick up the slack if the vehicle is to make good time, shining a space-based laser on the sail as it recedes into the dark depths.

But that's easier said than done, to put it mildly.

"You'd have to point [the laser] more accurately than we can point anything today to keep it focused on the sail," Johnson said. "And you'd have to put a lot of energy into it, so that the beam doesn't spread out and lose all that energy. The estimates I've seen are that you'd have lasers that have a power output basically comparable to the whole of humanity today."

The energy beam could be pretty much any type of electromagnetic radiation, including microwaves, said Richard Obousy, president of Icarus Interstellar, a nonprofit group devoted to pursuing interstellar spaceflight.

"You can actually reach reasonable fractions of the speed of light, a few percent of the speed of light," Obousy told SPACE.com.

Aim high

The challenges posed by insterstellar flight may seem insurmountable to us now. But Johnson is hopeful that humanity will overcome them someday, after we've expanded our footprint to cover a broad swath of the solar system.

Once we've become an interplanetary species that has mastered the ability to get raw materials and energy from space, then it'll be natural to turn our gaze to other stars, Johnson said.

"We're going to run into the problem of the limitations of the solar system eventually," he said. "So the next step will be, there's a whole galaxy out there. It's too big a step for us to take now, but I would like to think that several generations in the future, that'll just be the next logical step."

Obousy agrees that tapping the vast resources of the solar system will be a key step toward mastering interstellar flight. But he's more optimistic than Johnson about the timeline, saying that humanity has a good shot at launching its first interstellar mission by the end of the century.

"I think a lot of people tend to overestimate what we can accomplish in the short term, in the next five to 10 years," Obousy said. "But they also vastly underestimate what we can accomplish in the long term, decades or a century from now."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.