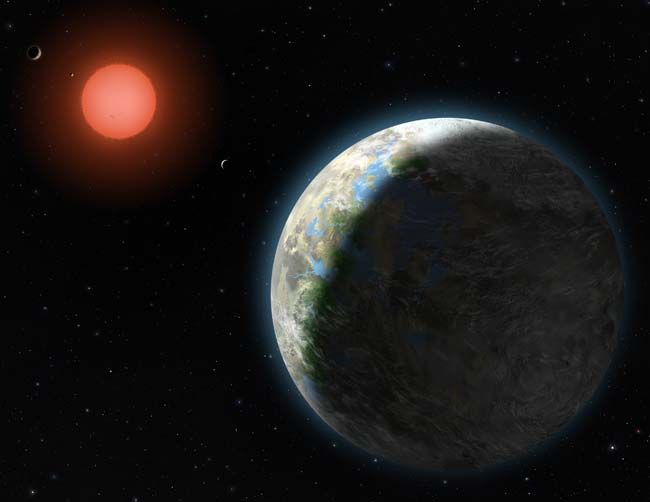

Every rocky planet likely develops a liquid-water ocean shortly after forming, suggesting that potentially habitable alien worlds may be common throughout the universe, a prominent scientist says.

The building blocks of rocky planets contain more than enough water to seed oceans, and computer models and Earth's own history suggest such seas should slosh around soon after these worlds' surfaces have cooled down and solidified, said Lindy Elkins-Tanton of the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C.

"Habitability is going to be much more common than we had previously thought," Elkins-Tanton said today (March 18) during a talk at the 44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas.

Making an early ocean

Analysis of ancient Earth rocks shows that our own planet hosted an ocean of liquid water at least 4.4 billion years ago, Elkins-Tanton said — just 160 million years or so after our solar system's birth. [9 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

This water came primarily from the planetesimals that glommed together to form Earth long ago rather than from comet impacts, as some researchers had previously believed, she added.

While comet-delivered water probably made a contribution later on, "it's not required," Elkins-Tanton said, citing studies that model planetary building blocks and how they come together. "You can make a water ocean without it."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For example, even if the pieces that built Earth contained just 0.01 percent water by weight, our planet still would have harbored an early global ocean hundreds of meters deep, she said.

Such primitive oceans form in a multistep process, Elkins-Tanton explained. Water first boils out of the molten rock covering a newborn terrestrial planet heated up by accretionary impacts, creating a steamy atmosphere. This atmosphere then collapses as the planet cools, returning the water to the surface and generating an ocean.

"The ramifications of this are that, in any exoplanet system anywhere in our universe, if it's made of rocky materials with similar water contents to ours, every rocky planet would be expected to start with a water ocean," Elkins-Tanton said.

Further, models developed by Elkins-Tanton and others "all indicate that this cooling and collapse process happens on the order of 10 million years or less," she added.

That's an exciting prospect for astrobiologists, as life on Earth is found nearly anywhere liquid water exists.

Holding on to the water

Of course, forming an ocean and holding onto it are two different matters. After all, Earth's solar system hosts rocky planets — Mercury, Venus and Mars — whose surface oceans have long since disappeared, if they ever existed at all.

Indeed, how some rocky worlds manage to retain their water is an area ripe for future research, Elkins-Tanton said, specifically citing the case of Venus, Earth's hellishly hot "sister planet" that veered down a very different road after its formation.

It may be tempting to ascribe the apparent dessication of rocky worlds like Venus to the giant impacts that pummeled them in our solar system's early days. But Earth held onto much of its water despite a massive collision with a Mars-size body (which is thought to have led to the formation of the moon), and data from NASA's Messenger spacecraft show that Mercury still harbors many volatile compounds, Elkins-Tanton said.

"Now if there would be a poster child for the body that should be depleted by giant impacts, that would be Mercury," Elkins-Tanton said. "Giant impacts do not dry bodies."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to Live Science. Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.