NASA's Mars rover Curiosity is back in action after being sidelined by a computer glitch for the second time in three weeks.

Curiosity went into a precautionary "safe mode" on Sunday (March 16), apparently because a file slated for deletion was connected to one still in use by the rover. But the mission team has now sorted things out and returned the robot to active status, NASA officials announced today (March 19).

The car-size Curiosity rover has not resumed science operations yet, however. It's still recovering from a separate memory glitch that knocked out its main, or A-side, computer in late February. Engineers swapped Curiosity over to its backup (B-side) computer at the time, spurring the rover to go into safe mode on Feb. 28.

Curiosity bounced back on March 2, only to stand down briefly once again a few days later to wait out a Mars-bound solar eruption. [Curiosity Rover's Latest Amazing Mars Photos]

Mission engineers continue to configure and check out the B-side computer, which remains the Curiosity rover's active computer. The A-side is now available as a backup if needed, officials said.

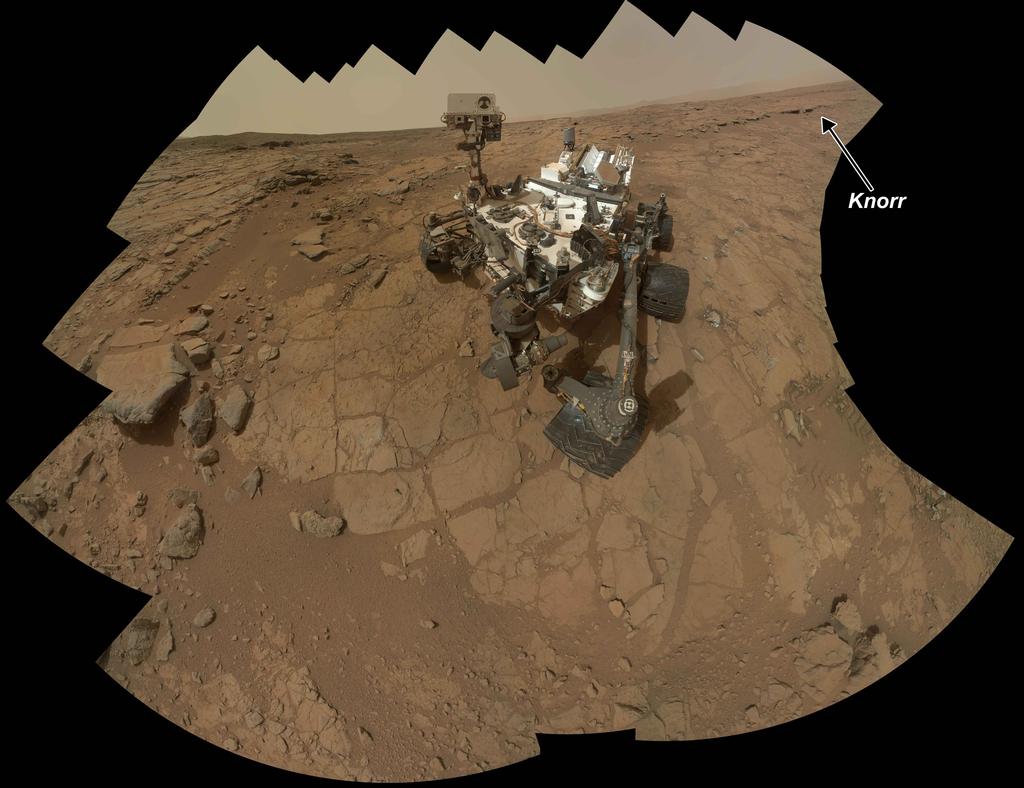

All of this drama has delayed Curiosity's activities at a Martian site called Yellowknife Bay, which mission scientists announced last week could have supported microbial life.

This discovery was based on Curiosity's study of material pulled out of a hole it drilled last month into a Yellowknife Bay rock. Further such analytical work should be possible soon, rover team members said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We expect to get back to sample-analysis science by the end of the week," Curiosity mission manager Jennifer Trosper, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement.

The rover team also wants to drill another hole in the Yellowknife Bay area to confirm and extend their previous observations. But this won't happen until May, partly because of an upcoming unfavorable planetary alignment.

Engineers won't send commands to the six-wheeled robot for most of April, because Mars and Earth will be on opposite sides of the sun during this time.

"The moratorium is a precaution against interference by the sun corrupting a command sent to the rover," NASA officials wrote in a mission update today.

Curiosity is the centerpiece of NASA's $2.5 billion Mars Science Laboratory mission. The huge robot touched down inside Mars' Gale Crater last August, kicking off a planned two-year surface mission to determine if the area ever could have supported microbial life.

While Curiosity has already achieved its main mission goal, the rover's handlers have no desire to rest on their laurels. They still plan to send Curiosity on to its main science destination — the base of 3-mile-high (5 kilometers) Mount Sharp — when it's done at Yellowknife.

Mount Sharp's foothills, which lie about 6 miles (10 km) from the rover at present, show signs of long-ago exposure to liquid water. The mountain's many layers also contain a record of how Mars' environmental conditions have changed over time, and researchers want Curiosity to read these layers like a book as it climbs up Mount Sharp's slopes.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to Live Science. Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.