Simple Visual Illusion Dupes Computer

Even computers can get tricked by optical illusions, a new study finds.

Such research may help shed light on how vision works in the brain, and lead to better computer recognition of images, scientists added.

Optical illusions, more properly known as visual illusions, take advantage of how the brain perceives what the eyes tell it in a way that plays a variety of tricks on the mind. For instance, these illusions may cause people to see something that is not there, or not see something that is there, or see an unrealistic portrayal of object, or see one thing as two or more completely different things. By investigating how illusions fool the brain, researchers can learn more about the brain's inner workings

"In most cases, illusions can be really useful," said researcher Astrid Zeman, a cognitive neuroscientist at Macquarie University in Australia. "For example, we watch television and see continuous movement instead of a flickering set of still images."

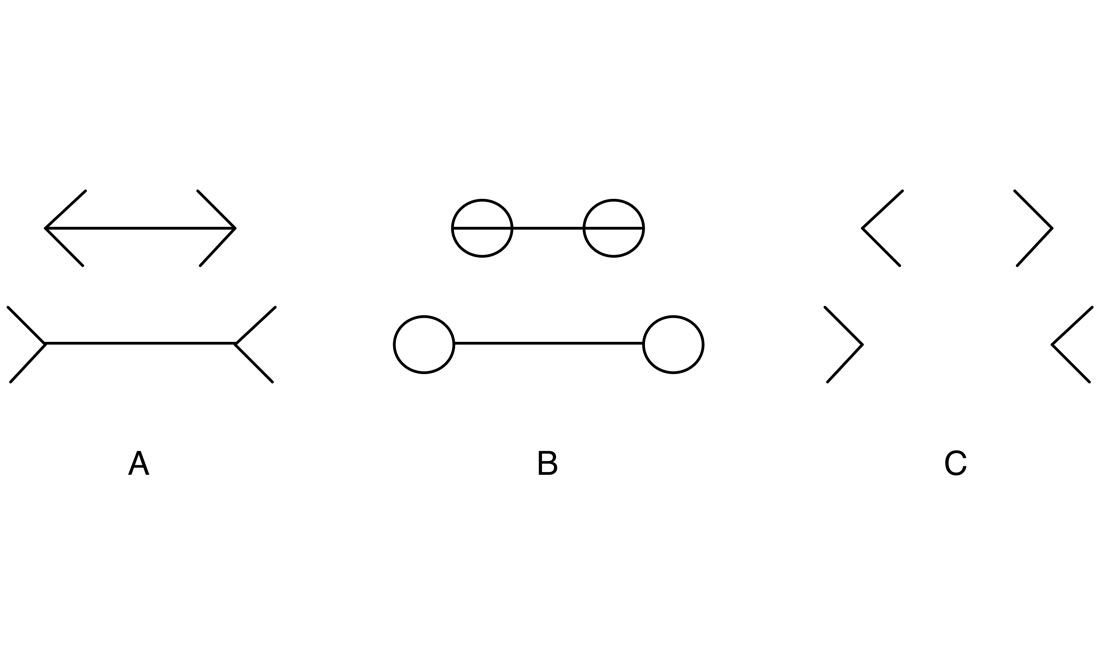

One classic visual illusion is the Müller-Lyer illusion, where arrowheads and arrow tails can influence the perceived length of a line. When arrowheads are placed at both ends of a line, they can make it look shorter than a line of equal length; when these are replaced by arrow tails, they can make it look longer. [Eye Tricks: Gallery of Visual Illusions]

There is ongoing debate as to what causes the Müller-Lyer illusion in the brain. To learn more, scientists experimented with a computer image-recognition model designed to mimic the brain's vision centers to see which might generate specific patterns of errors similar to ones expected from the illusion.

"Recently, many computer models have tried to imitate how the brain processes visual information because it is so good at it," Zeman said. "We are able to handle all sorts of changes in lighting and background, and we still recognize objects when they have been moved, rotated or deformed. I was curious to see whether copying all of the good aspects of object recognition also has the potential to copy aspects of visual processing that could produce misjudgments."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists discovered these artificial mimics of the brain could get duped by the illusion.

"What is exciting about these results is imagining what would happen in the future," Zeman told LiveScience. "If we build robots with artificial brains that are modeled off our brains, the implication is that these robots would also see illusions much like we do. By imitating the amazing accuracy, flexibility and robustness that we have in recognizing objects, we could also be copying potential errors in computation that manifest in visual illusions."

Tricking a computer

The researchers first showed pairs of lines to a computer model of human vision. Each pair had one line that was longer than the other. Each line either had both an arrowhead and an arrow tail or an "X" at both ends. The computer model, named HMAX, had to guess which line was longer, and it was told when it was correct and when it was wrong. In this way, the investigators trained the system to correctly identify what long and short lines look like with 90 percent accuracy.

"We train a biologically plausible model and look at the influence of the images it is exposed to," Zeman said. "If we think of this visual system as something we implant in a robot, this means that we can grow whole bunch of robots up in different environments. Then, once our robots have matured and have learnt to see things, we can then smash their brains open to see what they are thinking. This is something that we can't quite do with humans."

The scientists then tested the system with pairs of lines. Again, each pair had one line that was longer than the other. However, this time the top line always had two arrow tails and the bottom line always had two arrowheads. In humans, if both lines are actually the same length, the top line will look longer.

The researchers found the model was indeed mildly vulnerable to the illusion, losing about 0.8 percent to 1.6 percent accuracy. Also, the effect on the model was stronger when the angle of fins of the arrowheads and arrow tails was more acute, just as with humans.

"I got really excited when we first saw an illusory effect — we hadn't expected that to happen at all," Zeman said.

How illusions trick the mind

These findings may eliminate a number of potential explanations for the illusion. For example, in the past, scientists had speculated this illusion was caused by human brains misinterpreting arrowheads and arrow tails as depth cues — in modern-day environments, rooms, buildings and roads present boxy scenes with many edges, and so might lead people to unknowingly make predictions regarding depth whenever they run across angles and corners. However, since this computer model was not trained with 3D images, these findings may rule out that idea. [The 10 Greatest Mysteries of the Mind]

Previously, researchers had also conjectured this illusion resulted from human brains focusing more on overall information about shapes instead of on their constituent parts. However, that seems not to be true with the model either.

All in all, these findings suggest the illusion doesn't necessarily depend on the environment or any rules people learn about the world. Rather, it may result from an inherent property of how the visual system processes information that requires further elucidation.

Future research could help computers recognize illusions, so they can reject impossibilities and paradoxes. "This can be very important, for example, when judging the distances and sizes of objects in target-tracking systems," Zeman said.

The researchers now aim to model a range of different visual illusions, especially ones where there is ongoing debate as to what causes them.

"There are so many visual illusions that exist out there, and new ones are coming out all the time," Zeman said. "These illusions bring to light new questions about how we perceive the world and the assumptions we make about the world. Currently there is no existing formal and comprehensive catalog of illusions, so one direction for future development would be to pool together all of this knowledge."

The scientists detailed their findings online Feb. 15 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.