Roman Ruins Yield Clues to Ancient Earthquakes

The way the massive stone blocks making up a Roman mausoleum in Turkey were knocked off-kilter reveals clues to the power of the earthquake that rocked the structure.

Analyzing other ancient ruins for such damage could help shed light on the history of earthquakes in a region, which could yield insights on what risks that area faces in the future, the scientists who examined the mausoleum said.

The ruins of the city of Pınara date back at least 2,500 years to the ancient realm of Lycia in what is now southwest Turkey. It eventually became part of the Roman Empire.

"Pinara is a very exciting place because it has not been excavated yet," said Klaus-G. Hinzen, a seismologist at the University of Cologne in Germany. "You feel closer to ancient times than you would strolling through a museum with great artifacts."

Hinzen and his colleagues analyzed a Roman mausoleum in Pinara. Built under a sheer cliff nearly 330 feet (110 meters) high, it has a commanding view of the nearby forum and castle and the mountain range to the east.

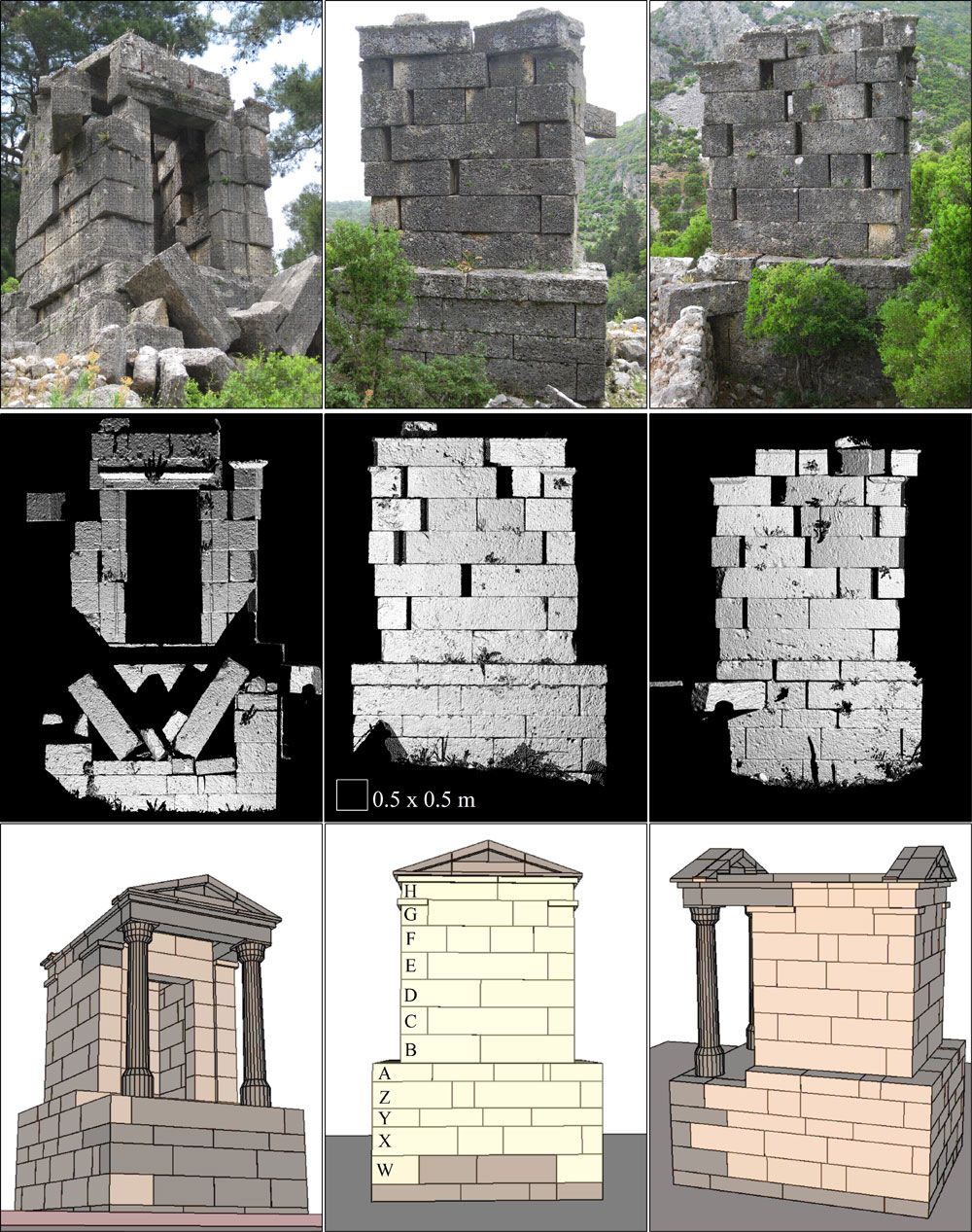

The mausoleum is mostly intact, but shows signs of damage. Most of its blocks have shifted heavily; some have fallen off its walls, and the front section of the mausoleum is collapsed, including its pillars.

Scientists were uncertain how the mausoleum was damaged. An earthquake seemed a likely culprit, but the cliff the mausoleum is built under is honeycombed with numerous other tombs, and damage from falling rock also seemed a plausible cause.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To help solve the mystery, researchers constructed a 3D model of the mausoleum based on 90 million data points from nine laser scans of the structure.

"Some objects we laser-scanned in Pinara caused more gardening work than geophysical work — we had to remove vegetation to get the laser beam a straight view to the targets," Hinzen said.

The scientists deduced the mausoleum was once made of about 180 stone blocks. Computer simulations analyzing the way it warped revealed that rockfall was not the likely major cause of its damage. Instead, it was likely an earthquake, and based on the level of damage the structure experienced, the simulations suggest the quake was potentially a magnitude 6.3 temblor. [Video: What Earthquake 'Magnitude' Means]

"I was astonished by the sensitivity with which the model of the building reacts to small changes in the ground motion," Hinzen told OurAmazingPlanet. "It is fascinating to watch the movements of the blocks during the calculations. Sometimes when you watch a block or column, you think, now it must topple, but at the end it doesn't."

These findings could help inform seismologists about the likely earthquake hazard this southwestern region of Turkey faces. Such work could also provide information on the effects of ancient earthquakes elsewhere in the world.

"Currently we are testing the hypothesis that the Mycenaean culture was brought to an end, at least in part, by strong earthquakes on the Peloponnese in Greece," Hinzen said. "We're concentrating our work on the Mycenaean citadels of Tiryns and Midea, a project in cooperation with archaeologists from Heidelberg University and Greece."

Hinzen and his colleagues Helen Kehmeier and Stephan Schreiber detailed their findings in the April issue of the journal Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

Follow OurAmazingPlanet @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.