NASA's Voyager 1 probe is tantalizingly close to the edge of the solar system, but predicting when it will finally pop free into interstellar space is a challenging proposition, mission team members say.

Voyager 1 is plying new and exotic terrain at the limits of the sun's sphere of influence, and scientists simply don't know what to expect from these unexplored regions.

"We've never been there before," said Voyager project manager Suzanne Dodd of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "That's what makes it very hard. It's not unlike the first explorers sailing across the Atlantic Ocean to the New World. They thought they might know what they would see, but they saw things that were quite a bit different."

Knocking on the door

Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, launched a few weeks apart in 1977 to study the giant planets Saturn, Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune. After completing this unprecedented "grand tour," the two probes kept flying, streaking through unexplored realms on their way to interstellar space. [Voyager: Humanity's Farthest Journey (Video)]

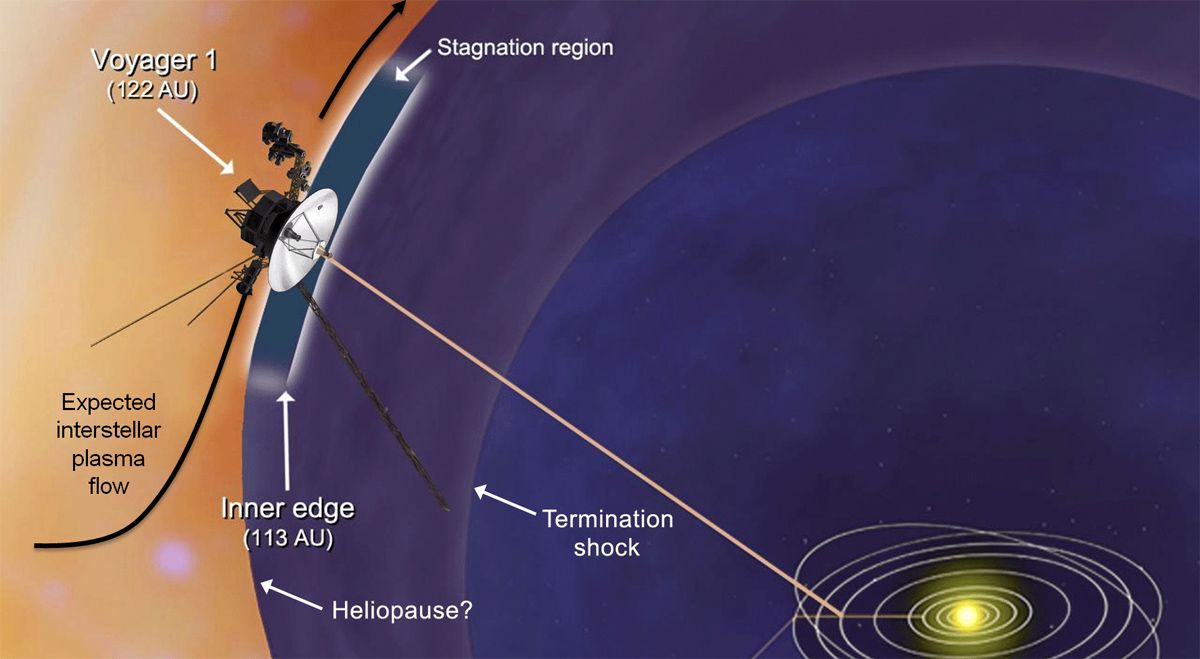

It looks like Voyager 1 will get there first. The probe is now more than 11.3 billion miles (18.2 billion kilometers) from Earth, making it the most farflung manmade object in the universe.

Voyager 1 has also encountered strange new conditions in the outer layers of the heliosphere — the huge bubble of charged particles and magnetic fields surrounding the sun — suggesting that the probe may be about to leave the solar system forever.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Specifically, Voyager 1 has seen a spike in the levels of ultrafast cosmic rays that originate in interstellar space, along with a big drop in the number of lower-energy particles coming from the sun. But the probe has yet to measure a shift in magnetic field orientation, another phenomenon that mission scientists expect to observe outside the solar system.

"The particle data very clearly state that we're in a new region of the heliosphere," Dodd told SPACE.com. "But the Voyager spacecraft still senses the same magnetic field that we've always sensed — in the same direction. It's increasing slightly in strength, but basically it's the same as it's been for several years."

Making the call

If and when Voyager 1 tells its handlers that the magnetic field has flipped from the solar system's roughly east-west orientation to a north-south one, then humanity will probably have reached beyond its own backyard for the first time ever.

But forecasting when that historic moment will come is difficult, Dodd and other mission team members have stressed, because scientists don't know for sure how far the heliosphere extends, or what conditions are like in its extreme outer reaches.

Voyager mission chief scientist Ed Stone, a physicist at Caltech in Pasadena, has estimated that the probe won't pop free for another two years or so, though he stressed that this is just an educated guess.

"That's not science — that's just saying scaling sort of suggests that," Stone told SPACE.com this past December.

The Voyager team is prepared for the unexpected, as both spacecraft have delivered plenty of surprises in their 35-year space journeys.

"Every discovery that we've made has really been things that were not predicted before we got there," Dodd said. "So this is just a continuation of Voyager's travels of discovery."

But Stone, Dodd and the rest of the Voyager team are doubtless hoping Voyager 1's big moment comes before 2020. A declining power supply will force engineers to shut down the first science instrument that year, and all of them will probably stop working by 2025.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.