A single compound could stop several viruses, including rabies and Ebola, in their tracks, new research suggests.

The findings, published today (March 21) in the journal Cell Chemistry and Biology, could eventually lead to a broad-spectrum medicine for many viral diseases, similar to the way antibiotics work on bacterial infections.

"This new approach appears to work on multiple viruses rather than one," said study co-author John Connor, a virologist at Boston University.

Elusive parasites

With a bacterial infection, doctors prescribe antibiotics without knowing the specific bacteria involved. But such one-size-fits-all treatments for viruses have remained elusive.

Partly, that's because bacteria can live on their own outside cells and have many parts that can be targeted by drugs — some of which are common to several types of bacteria. By contrast, viruses are parasites that co-opt the body's machinery to do their work, so it's much more difficult to find drug targets that will disable multiple viruses without targeting the body's cells as well, Connor said.

"The best analogy is if you're shooting at a bacterium, you can actually shoot at it, whereas if you're trying to shoot at a virus there's a lot of host proteins in the way," Connor told LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stopping the viral machinery

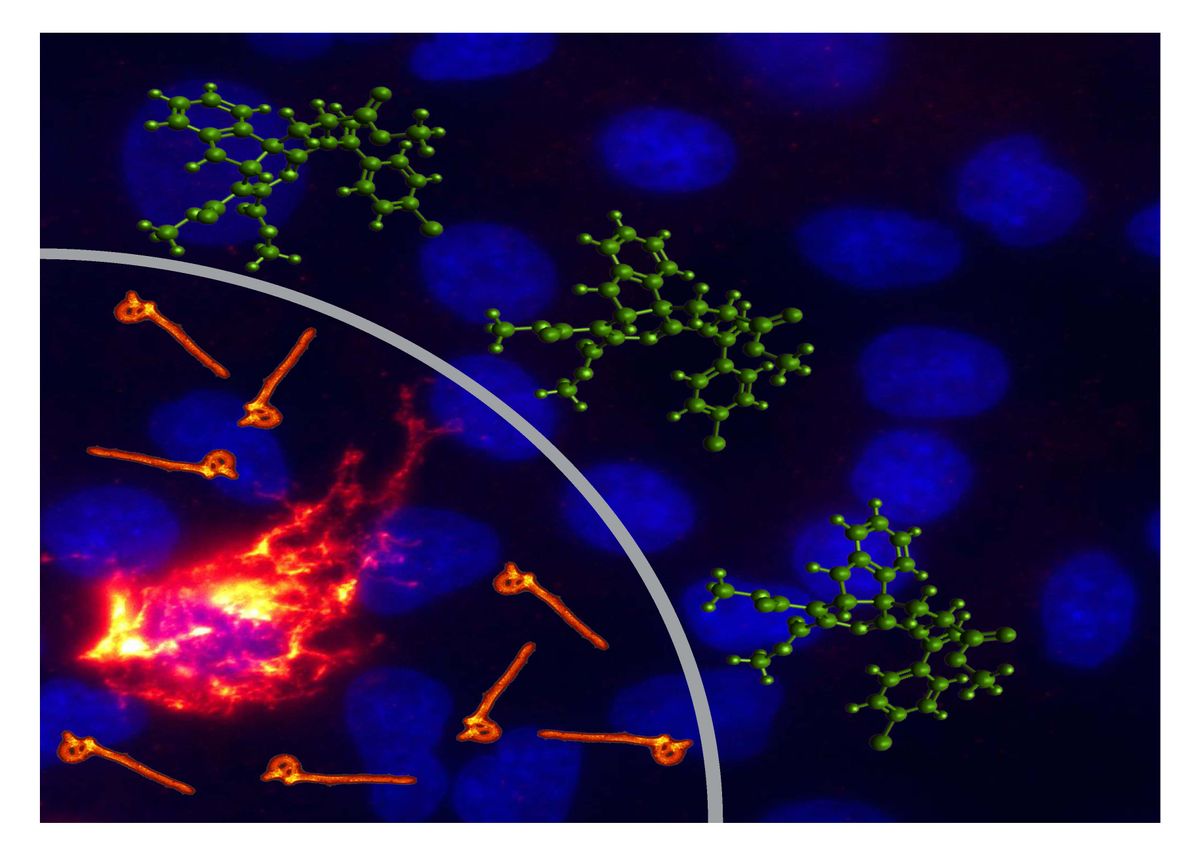

To remedy this problem, Connor and his colleagues studied a pathogen called vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), which replicates well in the lab and is related to Ebola, but isn't as deadly. They noticed that several viruses — including rabies, mumps and Nipah, a deadly virus carried by bats — used a similar method to make copies of themselves inside the body's cells.

They then searched for chemicals that would disable this copying process, finding a chemical that prevented VSV from replicating in a petri dish.

Because VSV makes copies in a similar way to other diseases, the team then tested the compound against Ebola and other related viruses, such as Rift Valley Fever, and found it also stopped them cold.

Through follow-up studies, the team determined that the new compound disables the machinery that the virus uses to copy its RNA, which is similar to DNA and carries the virus' genetic information.

Because viruses of this type use the same cellular machinery, the team believes that the compound could potentially treat a wide variety of viruses. To follow up, though, they need to prove that this compound is safe and can work in animals. They also need to test it against many other viruses.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter @tiaghose. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.