Beyond Higgs: 5 elusive particles that may lurk in the universe

More to find

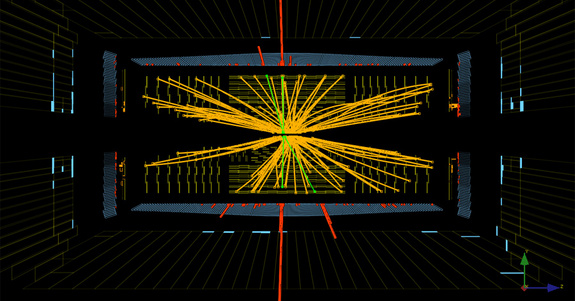

With the recent confirmation of a Higgs Boson discovery, many physicists were at least a little disappointed. That's because all signs point to it confirming the Standard Model, the decades-old theory that explains the tiny bits of matter that make up the universe.

But some physicists still hold out hope for results that could provide a bigger shake-up, looking for the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and physics experiments at other facilities to reveal other hidden particles lurking in the universe. From gravitons to winos, here are five bizarre things that may exist beyond the Higgs.

Gluinos, winos and photinos

If a theory called supersymmetry is true, there could be more than a dozen particles out there awaiting discovery. The theory holds that every particle discovered so far has a hidden counterpart.

In the Standard Model, there are two types of particles: bosons, which carry force and include gluons and gravitons; and fermions, which make up matter and include quarks, electrons and neutrinos, according to Indiana University physicist Pauline Gagnon's blog Quantum Diaries.

In supersymmetry, each fermion would be paired with a boson, and vice versa. So gluons (a type of boson) would have gluinos (a type of fermion), W particles would have winos, photons would have photinos, and the Higgs would have a counterpart called the Higgsino. [Wacky Physics: The Coolest Little Particles in Nature]

Unfortunately for advocates of supersymmetry, the LHC has so far found no traces of these elusive particles, suggesting that it is unlikely they exist, said Peter Woit, a mathematical physicist at Columbia University in New York.

In 2012, for instance, physicists discovered ultra-rare particles called B_s ("B-sub-S") mesons, which are not normally found on Earth, but which can sometimes exist fleetingly after two protons collide at near the speed of light. The rate at which they were observed fits with the Standard Model, meaning that any supersymmetric particles that do exist would have to be much heavier than initially hoped.

Another weakness of the theory: there are around 105 "free parameters," meaning that physicists don't have very good limits on the size and energy ranges within which the particles would be found. So scientists don't have a good idea of where to look for these particles.

Neutralinos

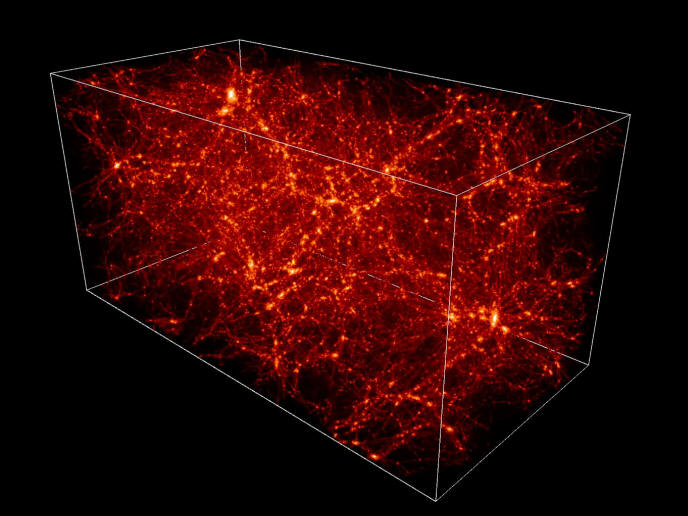

Supersymmetry also predicts that special particles called neutralinos, which carry no charge, could explain dark matter, the mysterious substance that makes up most of the universe's matter density, but is only detected by its gravitational pull. In supersymmetric theory, a mixture of all the force-carrier particles except gluinos would create neutralinos, according to Gagnon's blog.

Neutralinos would have formed in the scorching early universe and left enough traces to explain the presence of dark matter whose gravitational pull is felt today.

Gamma-ray and neutrino telescopes could hunt for these elusive particles in areas chock full of dark matter, such as the solar or galactic cores. In fact, physicists recently announced big news: a particle collector on the International Space Station may have found evidence of dark matter, though details aren't out yet.

Gravitons

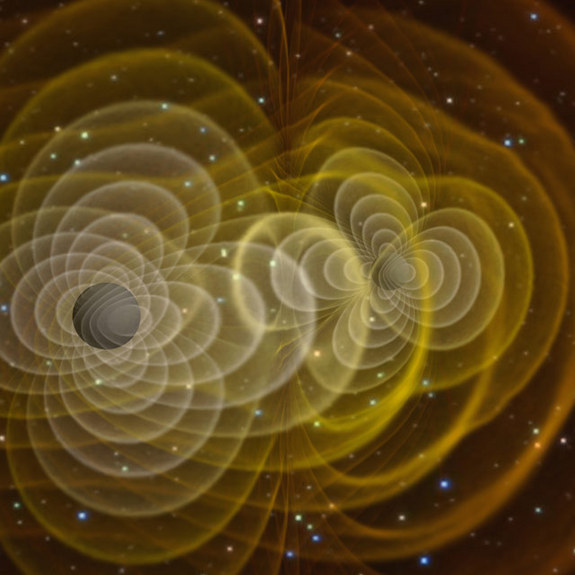

It stumped Albert Einstein, and it's puzzled physicists ever since: How to create a single theory that captures all the fundamental forces, such as gravity, and the behavior of quantum particles. For instance, the reigning theory of particle physics doesn't encompass gravity.

That question has led physicists to propose quantum gravity particles known as gravitons, which are tiny, massless particles that emit gravitational waves. In theory, each graviton would exert a pull on the matter in the universe, but the particles would be difficult to detect because they interact weakly with matter. [6 Weird Facts About Gravity]

Unfortunately, directly detecting these shadow particles would be physically impossible with current technology. The hunt for gravitational waves using tools such as LIGO could reveal the existence of gravitons indirectly, however.

The unparticle

Recently, scientists found traces of another bizarre particle, called the unparticle. It could carry a fifth force of nature, that of long-range spin-spin interactions. On smaller scales, a short-range spin interaction is common: it's the force that aligns the direction of electron spin in magnets and metals. But longer interactions are much more elusive. If this force exists at all, it would have to be a million times smaller than that found between an electron and a neutron.

To find the unparticle, physicists are searching inside Earth's mantle, where tons of electrons are packed together, aligned with Earth's magnetic field. Any small perturbation in that alignment could reveal a hint of the unparticle.

Chameleon particle

Physicists have proposed an even more elusive particle, the chameleon particle, which would have a variable mass. If it exists, this shape-shifter could help explain both dark matter and dark energy.

In 2004, physicists described a hypothetical force that could change depending on its environment: in places with tightly packed particles such as Earth or the sun, the chameleon would exert only a weak force, whereas in sparsely packed areas it would exert a strong force. That would mean it would start out weak in the densely packed early universe, but would get stronger as galaxies flew outwards from the center of the universe over time.

To find the elusive force, physicists would need to discover evidence of a chameleon particle when a photon decays in the presence of a strong magnetic field. So far, the search hasn't yielded anything, but experiments are ongoing.

Follow Tia Ghose @tiaghose. Follow us @livescience, Facebook or Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.