Physicists at an underground laboratory have caught an ultra-rare particle in the act of reappearing.

For only the third time, scientists have detected elementary particles called neutrinos in the act of changing from one type, called muon, to another, called tau, on the several-hundred-mile trip between two laboratories.

"It proves that the muon neutrinos are some kind of Superman-type particle: They get into a phone booth somewhere in between and change into something else," said Pauline Gagnon, a particle physicist at Indiana University, who was not involved in the experiment.

The new discovery bolsters the theory that the sneaky neutrinos oscillate from one type to another, which is why physicists detect fewer coming from the sun than predicted. [Wacky Physics: The Coolest Little Particles In Nature]

Sun particles

The nuclear reaction that powers the sun also produces massive numbers of solar neutrinos, tiny, uncharged particles that reach Earth and pass virtually undetected through ordinary matter, said researcher Antonio Ereditato, a physicist at the University of Bern in Switzerland and a member of the team that conducted the experiment, called OPERA (Oscillation Project with Emulsion-tRacking Apparatus).

"Each square centimeter of your body is touched every second by 60 billion neutrinos from the sun," Ereditato told LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But for the last two decades, scientists have detected fewer neutrinos from the sun than they expected.

The dominant explanation for this neutrino shortage, proposed in 1957 by Italian physicist Bruno Pontecorvo, argued that neutrinos oscillate between three flavors, or types: electron, muon and tau.

As a result, neutrinos seem to disappear, because detectors try to measure them in one flavor when they have oscillated to another one.

Scientists have caught many neutrinos in the act of disappearing. But catching neutrinos as they appear has been far more elusive — since 2010, only two other tau neutrinos have been discovered.

Reappearing particles

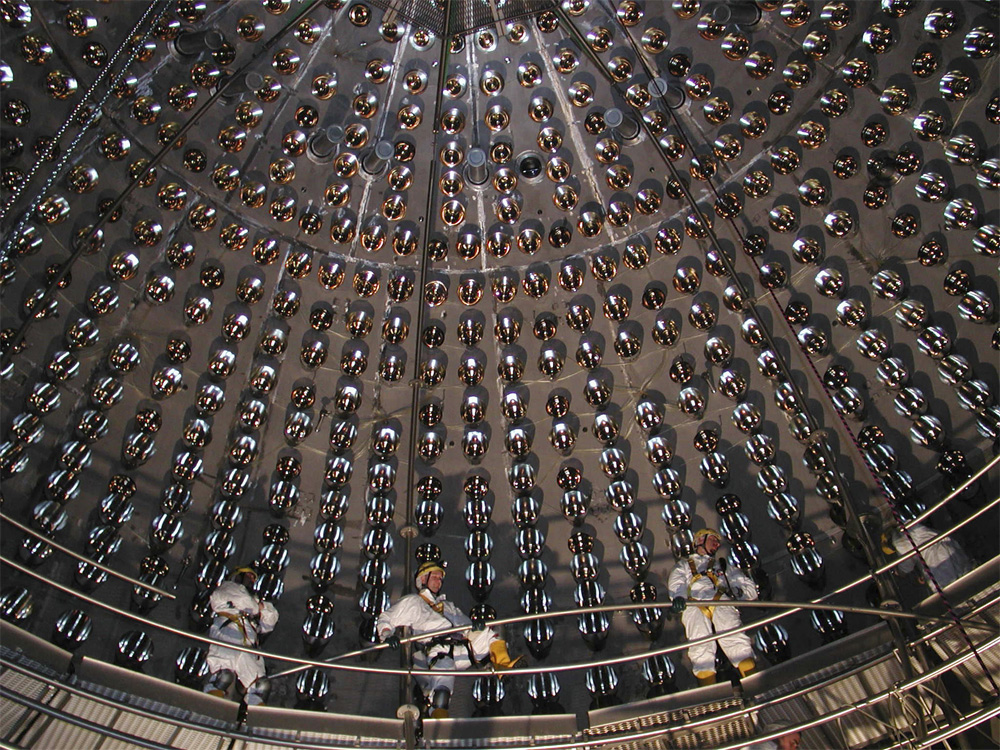

To find these rare events, physicists with the OPERA project shot a beam of muon neutrinos from the physics lab CERN in Switzerland 454 miles (730 kilometers) through the Earth's crust to Gran Sasso Laboratory, buried underneath a mountain in Italy.

During the travel, a very small fraction of the neutrinos naturally changed flavor, and when they reached the laboratory some tiny fraction of them were detected by a 4,000-ton "camera," transforming into a similar flavored particle and then decaying after a short distance. These fleeting events produce a faint blip of light recorded by one of 9 million photographic plates, Gagnon told LiveScience.

Because neutrinos have no charge, they only interact with matter through the weak force, which doesn't happen very often, Gagnon said.

Tau neutrinos morph into tau particles that travel for such just a few millimeters before decaying into hadrons, so they are even harder to detect.

The newly discovered tau neutrino bolsters the notion that the discovery of two others, in 2010 and 2012, were real.

This detection is statistically quite strong: The chance that the researchers are mistaken is about one in a million, Ereditato said.

The findings could provide other insights into tau neutrinos.

"Neutrinos have a mass and measuring this mass is quite difficult, because it's extremely small," Gagnon said.

But because neutrinos' mass determines how quickly they oscillate, and in turn how frequently they should be detected, finding tau neutrinos could help physicists nail down these elusive particles' mass, she said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter @tiaghose. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.