Diary of a Dying Mom

"I will nurture them for as long as I can, and then trust that the world will take over from there." — Michelle Mayer

The hundreds of herbal and vitamin concoctions promising to boost immunity and fight disease may leave you thinking that there's no limit to how strong the immune system can be.

None of these pills do much of anything aside from enriching the purveyors of these products, perhaps so that they can upgrade their business plan and finally move their merchandise from the back of their garage into an insect-proof self-storage unit.

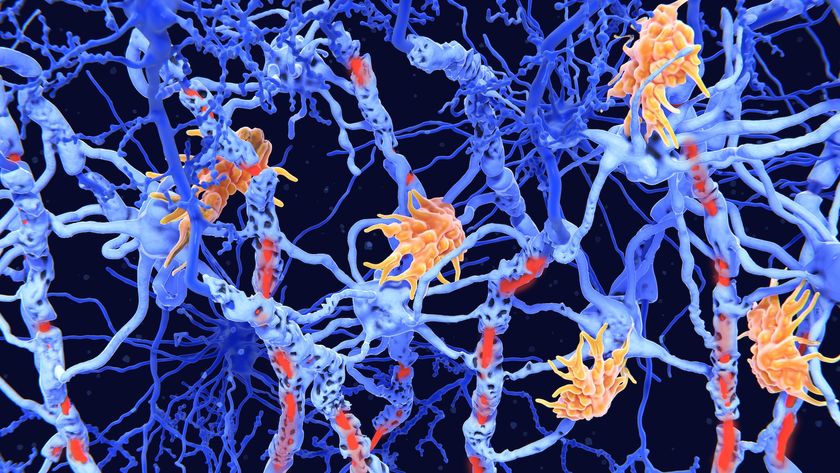

But maybe it is a good thing that the immune system can't be supercharged by wheatgrass, echinacea or other types of caterpillar food. The immune system is complicated, and it does have its limit. Millions of Americans, in fact, suffer from diseases brought on by the opposite of low immunity — a hyperactive immune system that attacks its host.

The phenomenon is called autoimmunity. One of the most common autoimmune diseases is rheumatoid arthritis, when the immune system attacks the joints. Another painful and potentially deadly autoimmune disease is scleroderma, in which the skin and lining of the organs turn brittle.

Sometimes autoimmune diseases are treated with (you guessed it) immunosuppressant drugs. Hold the wheatgrass.

The demand for immune-system boosters highlights a Western approach to so-called natural health care, which often has no sense of balance. If, for example, a little ginseng is healthy, then a greater dose of it must be healthier, the logic goes. We see this in megadoses of vitamins, containing far more nutrients than the body needs or likely wants.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Eastern medicine does have this sense of balance. Various types of ginseng are prescribed for specific diseases, not made into a sugary tea and sold in 24-ounce cans for anyone feeling a bit sluggish. Similarly, no respectable practitioner of Eastern medicinal arts would offer an immune booster to a healthy individual.

In the interest in restoring some balance — to highlight the fact that the body is far more complicated than what's captured in B-movie scripts peddled to consumers such as the battle between good antioxidants and bad free radicals — I would like to call your attention to a blog of someone dying from scleroderma.

The name of the blog sums it up: Diary of a Dying Mom. A recent entry about a conversation between mother and daughter is particularly poignant:

"I used to think I had made a mistake by having them, that I had been terribly unfair in sentencing them to this heartache. But I finally realized that came from a pretty egotistical view of motherhood: that life is only worth living if your mom is there to raise you. Amelia and Aidan do not belong to me; they belong to the world. I was merely a vessel for them. And I will nurture them for as long as I can, and then trust that the world will take over from there."

This woman, Michelle Mayer, is a friend of mine; I've known her for more than half my life. She's bright and health-conscious and was indeed healthy until scleroderma hit her for no known reason about 10 years ago. She's not sure whether she will live another month, let alone another year. Her blog is about dying but also about life and raising children while dealing with a chronic and likely terminal disease.

The blog also mirrors this Bad Medicine column, I think, in highlighting the fact that all this talk about health — about exercising, eating right, not smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, etc. — is to minimize the risk of disease. There are no guarantees. You can do everything right and still find yourself to be a dying mother at age 39.

Christopher Wanjek is the author of the books "Bad Medicine" and "Food At Work." Got a question about Bad Medicine? Email Wanjek. If it’s really bad, he just might answer it in a future column. Bad Medicine appears each Tuesday on LiveScience.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.