Vicious Shark-Tooth Weapons Reveal 2 Lost Species

A collection of vicious weapons made of shark teeth reveals that two species of sharks vanished from the reefs of Kiribati before scientists even noticed the species were there.

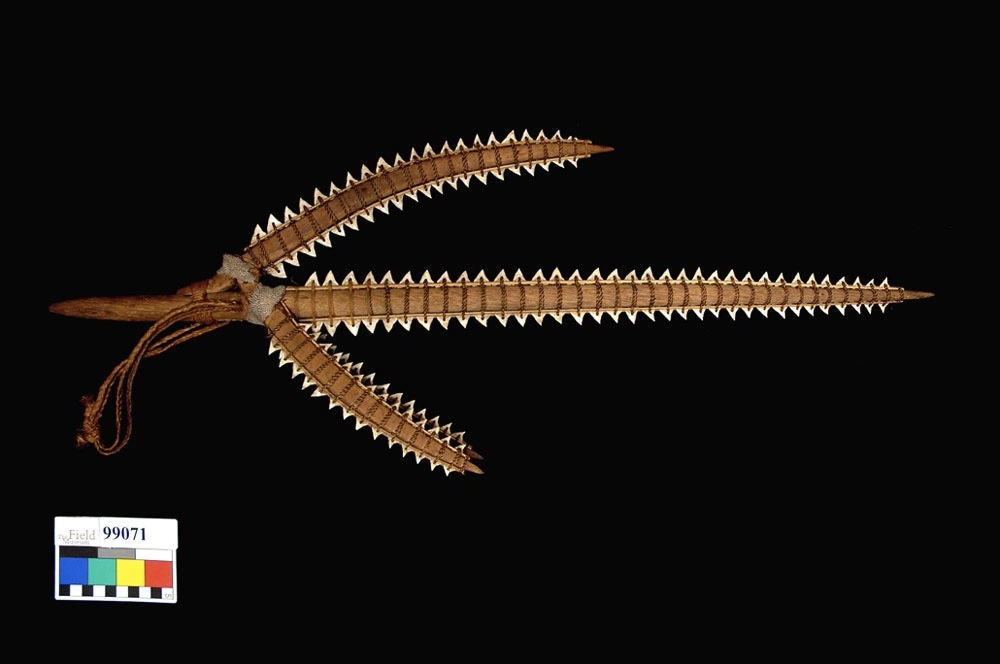

Until about 130 years ago, residents of the Gilbert Islands, which make up much of the Republic of Kiribati in the Pacific Ocean, used teeth from dusky sharks (Carcharhinus obscrus) and spotfin sharks (Carcharhinus sorrah) to make swords, spears, daggers and other fearsome weapons. Today, spotfin sharks can be found near Australia and Indonesia, and dusky sharks can be spotted near Fiji ― but neither plies the waters around Kiribati.

"We're losing species before we even know that they existed," said study researcher Joshua Drew, an ichthyologist at Columbia University. "That just resonates with me as fundamentally tragic."

Toothy weapons

Sharks have long been a major part of the Gilbert Islands’ culture, as the animals played a role in Kiribati myths and rituals, Drew told LiveScience. The first European visitors to the islands in the late 1700s noted the native inhabitants’ craftsmanship of weapons made of shark teeth. Weapon-makers would drill tiny holes in the teeth and secure them to wooden handles using coconut fibers and human hair. The results were daunting: all sharp points and serrated sides. [Image Gallery: Amazing Great White Sharks]

Drew and his colleagues were looking for ways to tie sharks into their culture in order to get people excited about conservation. They were "poking around" in the anthropology collections of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, when museum anthropologist Christopher Philipp, also one of the study authors, asked if they'd like to see some shark-tooth weapons.

"Anytime anybody asks you that question, your natural response is 'Yeah!'" Drew said. "They're cool."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The weapons were scientifically cool, too. Shape, serration patterns and other features of shark teeth were enough for researchers to identify the species. That meant Drew and his colleagues could figure out what kind of sharks the people of the Gilbert Islands were catching before scientific expeditions to the atolls were ever launched.

Vanished species

Using field guides and the museum's collections of shark jaws, the researchers identified teeth from eight species of shark on 122 weapons and teeth collections from the Gilbert Islands. The most common of those species was the silvertip shark (C. albimarginatus), whose teeth graced 34 weapons. Gilbert Islands weapon-makers also used teeth from silky sharks, oceanic whitetip sharks, tiger sharks, blue sharks and hammerheads.

Most surprising to scientists, however, was the discovery of dusky and spotfin sharks' teeth, as no scientist has ever recorded those sharks in Gilbert Islands reefs. It's unlikely that these two commercially valuable species would have been overlooked, the researchers wrote in a study published today (April 3) in the journal PLOS ONE, so it seems that the sharks simply vanished before anyone started taking a census.

"Probably, they were fished out," Drew said. Extensive shark-finning operations started in the region by the early 1900s, and in 1950 alone, fisherman pulled almost 7,716 pounds (3,500 kilograms) of shark fins (and only fins) from Gilbert Island waters. (Scientists now estimate that 100 million sharks are killed worldwide each year.)

The findings underscore the connection between Gilbert Islanders and sharks, Drew said. Kiribati has been a world leader in marine conservation, he said, adding that he hopes the findings will encourage more of that work. The discovery of previously unknown sharks in the area also pushes conservationists not to "set the bar too low" for Gilbert Islands reefs, Drew said, given that at one point, they supported more biodiversity than they do today.

"We shouldn't pack up and call it a day because we have two species of sharks there," Drew said. "We can do better."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.