Gallery: Tiny Dino Embryos

Tiny Dinosaur Fossil

A tiny dinosaur embryo bone found in a bed in Yunnan Province, China. The bones, which probably belonged to the long-necked Lufengosaurus, are among the oldest embryonic dinosaur bones ever discovered.

Yunnan Fossil Site

Researchers survey a fossil site in Yunnan, China, where they discovered more than 200 embryonic dinosaur bones. They reported their discovery April 11, 2013 in the journal Nature.

Digging for Dino Babies

Scientists huddle around the 3-foot (1-meter) square bone bed that once represented a Lufengosaurus nesting site.

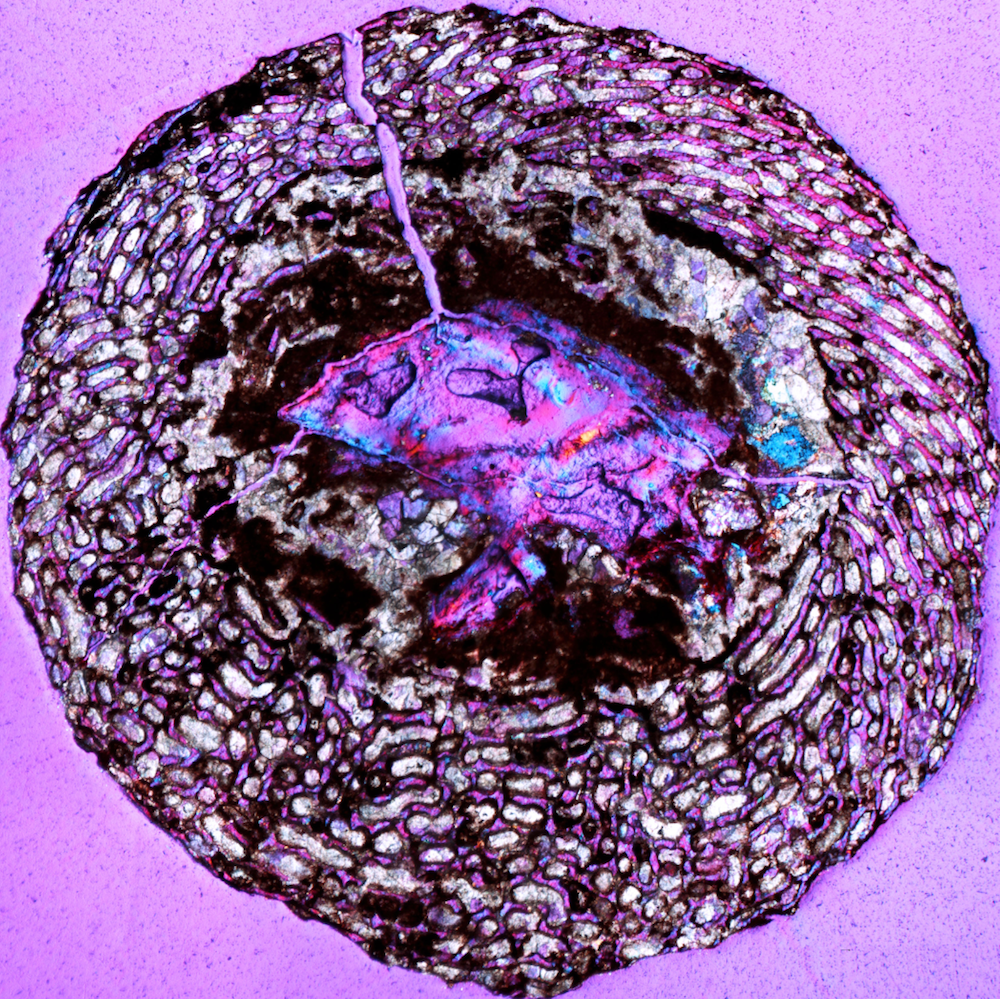

Leg Bone Section

A cross-section of an embryonic dinosaur femur found in Yunnan, China. The honeycomb-like area is bone tissue with large spaces for blood vessels, indicating rapid growth of the bone.

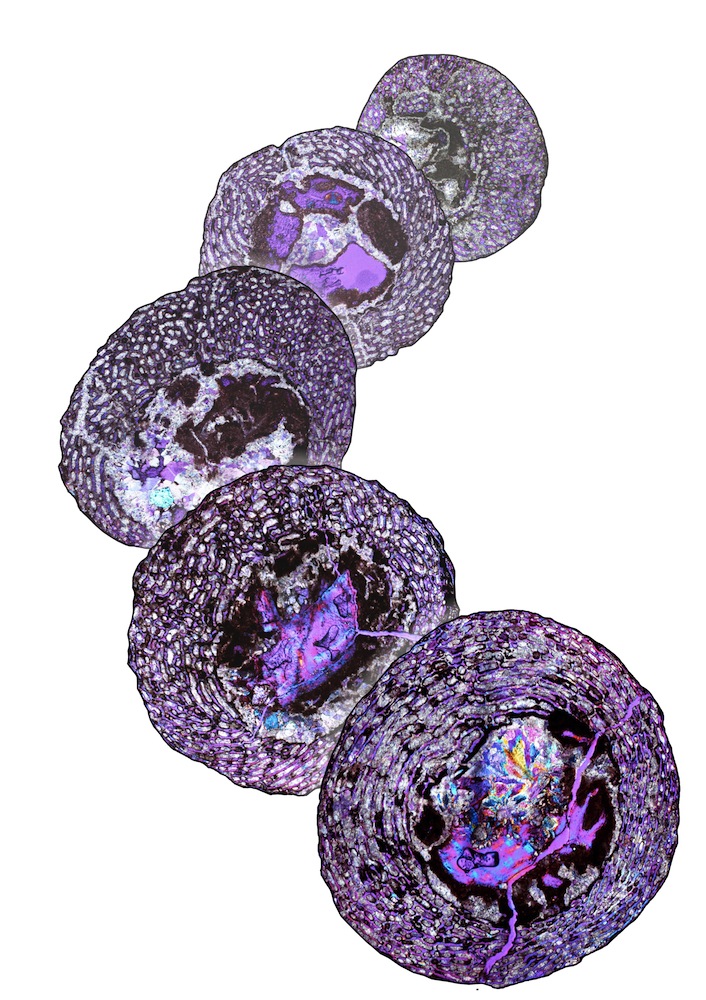

Dino Bone Growth

Cross-sections of the smallest to largest Lufengosaurus femur bones, showing how the bones changed throughout embryonic development.

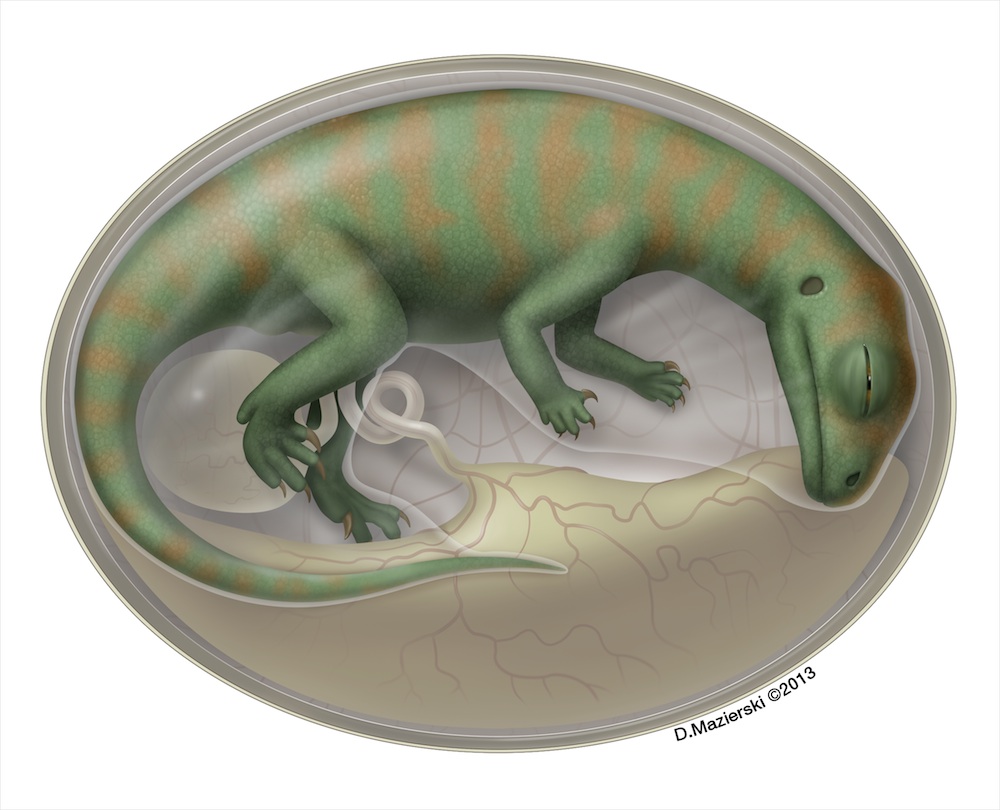

Dinosaur embryo

An artist's impression of Lufengosauarus inside the egg.

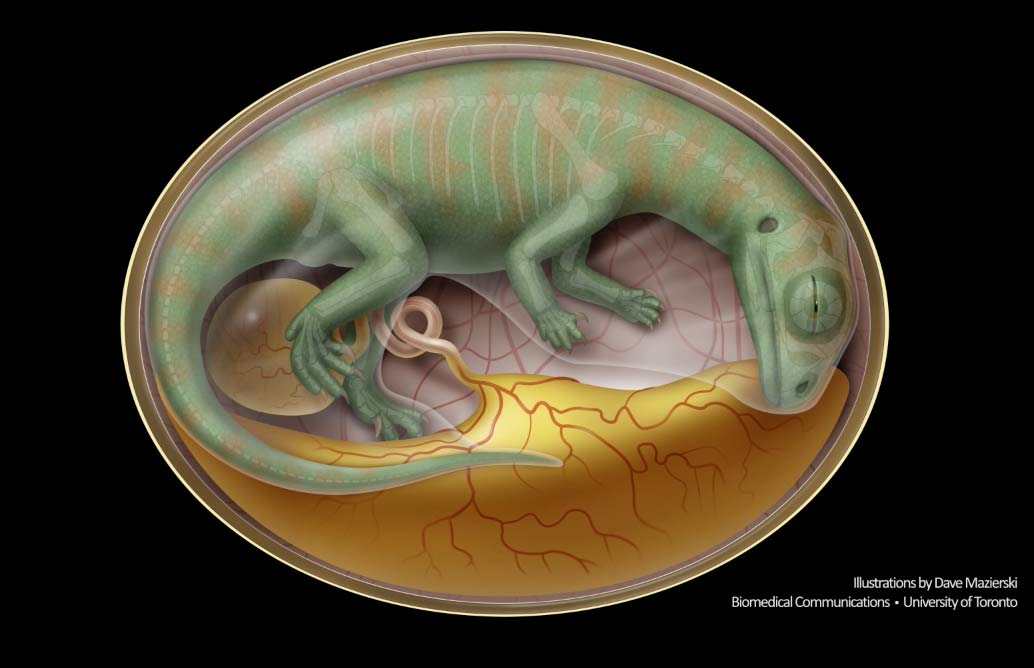

Embryo Bones

An artist's impression of an embryonic Lufengosaurus, showing the dinosaur's growing skeleton.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lufengosaurus

Lufengosaurus grew to be about 20 feet (6 meters) in length.

Same-Aged Embryo

This is a close-up of an embryonic skeleton of the dinosaur Massospondylus from a clutch of eggs at the 190-million-year-old nesting site found in the Golden Gate Highlands National Park in South Africa. The Yunnan find and the South Africa find are about equal in age as the oldest known dinosaur embryos.

Crowded Nest

Another baby dinosaur find, this one from Mongolia. This nest contains the remains of 15 infant Protoceratops andrewsi, a sheep-sized plant-eater related to Triceratops.

Big Mama

The fossil remains of a nesting Oviraptor, dubbed "Big Mama," complete with eggs. When this fossil was originally discovered in the 1920s, paleontologists believed the oviraptor mama was preying on the eggs of another species. Turns out, they were hers.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.