Instead of just killing off cancer cells directly, chemotherapy works because it prompts the body's own defenses to destroy tumor cells, new research in mice suggests.

The findings, published April 4 in the journal Immunity, suggest the immune system plays a critical role in fighting cancer.

"You need the host immune system — the reaction against the tumor — to work," said study co-author Guido Kroemer, an immunologist at the National Institute of Health and Medical Research in France.

If follow-up studies in people show a similar effect, doctors could boost the immune response to increase chemotherapy's effectiveness or measure a patient's immune response to specific drugs to predict chemotherapy's success, Kroemer told LiveScience.

Killer drugs

Until now, scientists had a limited understanding of how chemotherapy works. They assumed that the treatment worked by selectivelykilling more tumor cells than healthy cells, Kroemer said.

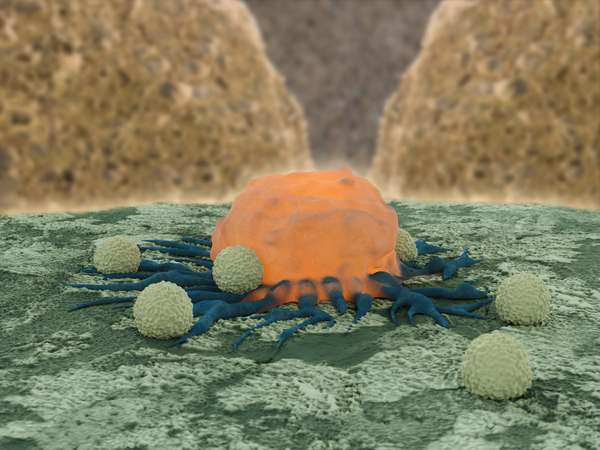

But the immune system also seemed to play a role. For instance, past work showed that chemotherapy required a particular immune cell type — called T-lymphocytes, or T-cells — in order to work against breast cancer.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Immune response

To understand how T-lymphocytes identified tumor cells, Kroemer and his colleagues marked cancer cells in mice with a protein that glowed green. They then watched what happened to those cells after they gave the mice an anthracycline, a specific type of chemotherapy. Anthracyclines are used to treat breast cancer, as well as prostate and lung cancer.

The researchers found that specific immune cells were drawn to a chemical signal from the tumor cells and then presented them to the T-lymphocyte immune cells.

To show that this cell played a key role in chemo's effectiveness, the team showed that mice lacking these presenting molecules had a marked reduction in chemotherapy response.

The research suggests that the immune system may play a wider role in fighting cancer than previously thought, Kroemer said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter @tiaghose. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.