It's Fall on Titan: Icy Cloud Marks Saturn Moon's Season

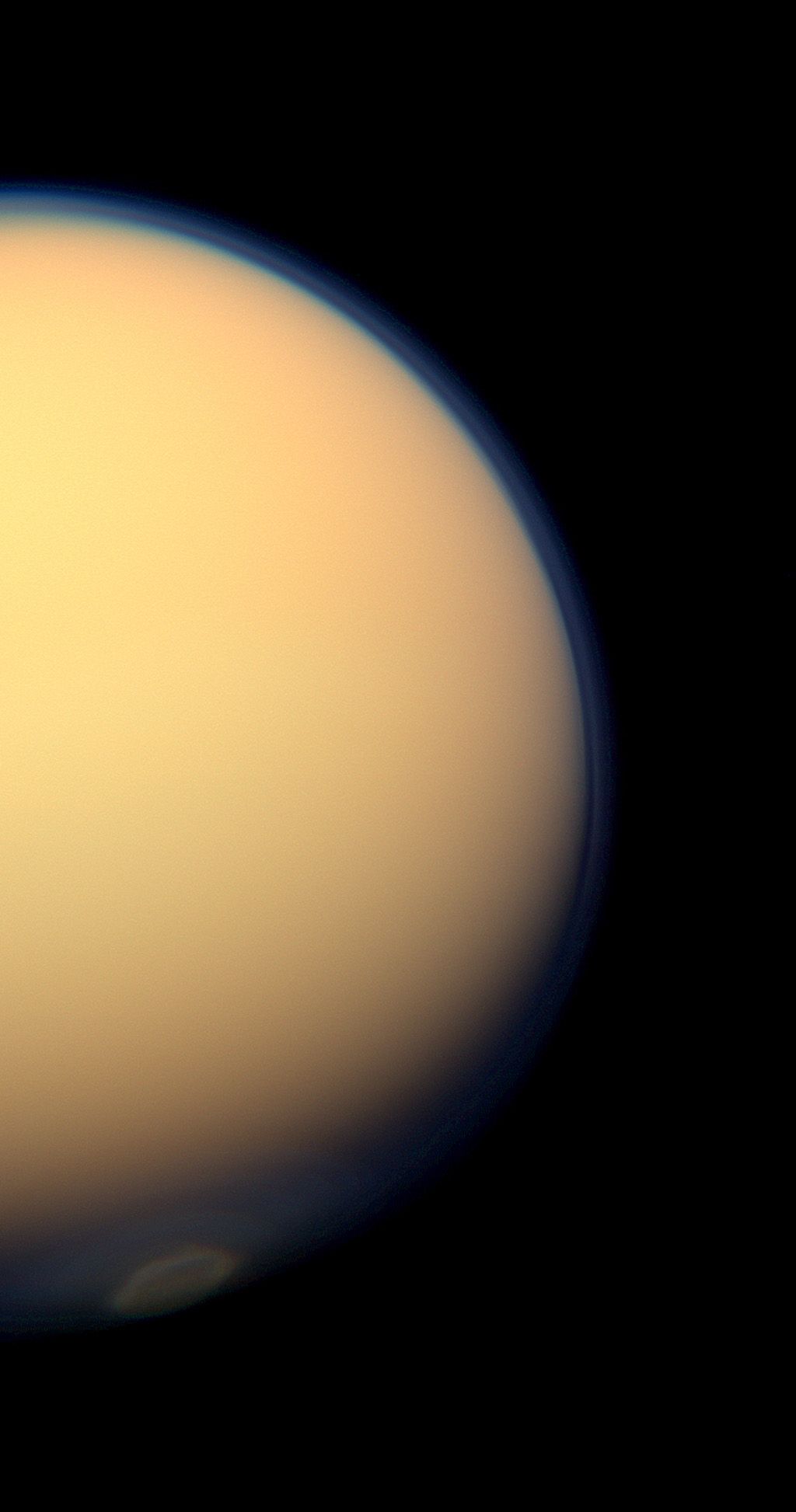

Images and data from NASA's Cassini spacecraft show that an icy cloud is growing over the south pole of Saturn's largest moon, Titan, hinting that a seven-year fall has taken hold on the celestial body's southern hemisphere.

Researchers don't know what the budding cloud is made of, but the same icy haze has been clearing over Titan's north pole, where it is springtime.

"We associate this particular kind of ice cloud with winter weather on Titan, and this is the first time we have detected it anywhere but the north pole," Donald E. Jennings, of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., said in a statement. The research by Jennings and his colleagues is based on observations with the composite infrared spectrometer (CIRS) on the Cassini probe, which has been studying Saturn for nearly a decade.

Titan is the second-largest moon in the solar system and the only one with clouds and a dense, planet-like atmosphere. Earlier observations by Cassini showed that warm air from Titan's southern hemisphere was rising high in its atmosphere and then being dumped over the moon's north pole, where it cooled and descended, forming an icy cloud. (The pattern is similar to the Hadley cell on Earth, which transports heat from the tropics to the subtropics.)

The new Cassini observations suggest this large-scale pattern of air flow over Titan has reversed direction, and winter is coming for the moon's southern hemisphere.

Titan's north pole officially began its transition from winter to spring in August 2009, and the researchers now believe that the circulation shift occurred that year. But the southern ice cloud wasn't spotted until July 2012, and scientists only saw the first hints of the change over the south pole in early 2012, when Cassini detected a high-altitude "haze hood," a swirling polar vortex and other features linked to cold weather.

"This lag makes sense because first the new circulation pattern has to bring loads and loads of gases to the south pole," Carrie Anderson, a CIRS team member and Cassini participating scientist at Goddard, said in a statement from NASA. "Then, the air has to sink. The ices have to condense. And the pole has to be under enough shadow to protect the vapors that condense to form those ices."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As for the ice clouds' composition, scientists say they have ruled out some chemicals, including methane, ethane and hydrogen cyanide. Whatever the makeup, the clouds could play a role in the complex chemistry of Titan's atmosphere.

"What's happening at Titan's poles has some analogy to Earth and to our ozone holes," Goddard's F. Michael Flasar, CIRS principal investigator, said. "And on Earth, the ices in the high polar clouds aren't just window dressing: They play a role in releasing the chlorine that destroys ozone. How this affects Titan chemistry is still unknown. So it's important to learn as much as we can about this phenomenon, wherever we find it."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.