Top 5 Discoveries by Mars Rover Curiosity (So Far)

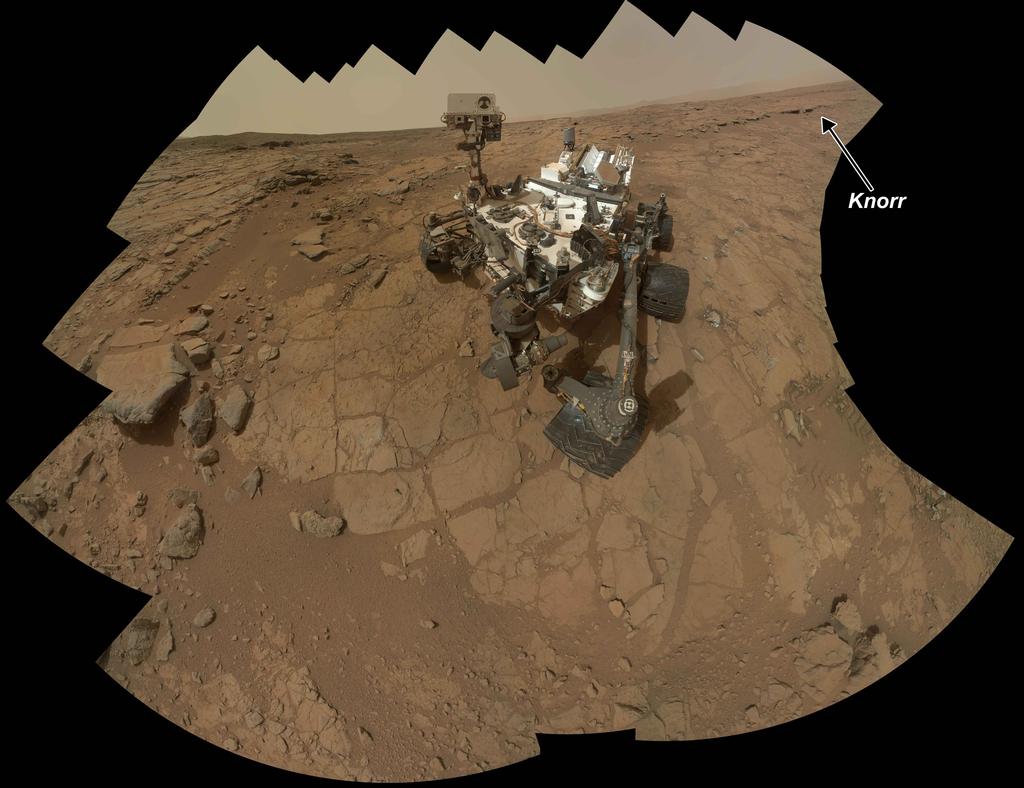

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has only been exploring the Red Planet since last August, but the robot has already racked up quite a string of accomplishments.

For starters, the rover's dramatic "seven minutes of terror" touchdown successfully demonstrated a new technique that can land big payloads with unprecedented precision, potentially helping pave the way for human outposts on the Red Planet.

And then there's the science. Curiosity was tasked with determining if its Gale Crater landing site has ever been capable of supporting microbial life, and the car-size robot managed to answer that question just seven months into a planned two-year surface mission.

Here's a brief rundown of Curiosity's biggest scientific and engineering achievements to date, a list that will surely grow as the car-sized robot journeys deeper into its planned two-year surface mission on the Red Planet. [Countdown: Curiosity's Top Accomplishments]

Sticking the landing

In a move that had never been tried before on another planet, a rocket-powered sky crane lowered Curiosity to the Martian surface on cables, then flew off and crash-landed intentionally a safe distance away.

Curiosity also touched down within a target ellipse that measured merely 12 miles long by 4 miles wide (20 by 7 kilometers), a huge improvement from the 2004 landing of NASA's twin Spirit and Opportunity rovers, whose ellipses spanned 93 miles by 12 miles (150 by 20 km).

This new landing system, which combines power and precision, should aid both manned and unmanned Mars missions in the future, NASA officials have said.

Finding an ancient streambed

Seven weeks after Curiosity touched down, mission scientists announced that the rover had found an ancient streambed where water once flowed at roughly knee-deep levels for thousands of years at a time.

The discovery suggests that at least some parts of Mars may have been habitable billions of years ago, since life here on Earth thrives pretty much anywhere liquid water is found.

Measuring Red Planet radiation

Curiosity has been assessing the Martian radiation environment, helping scientists better understand the hazards radiation may pose both to potential indigenous microbes and to human visitors on the Red Planet.

The news so far is encouraging, at least on the colonization front. Curiosity's measurements, the first of their kind ever taken on the surface of another planet, suggest that Martian radiation levels are comparable to those experienced by astronauts aboard the International Space Station.

Curiosity observed substantially higher radiation levels during its eight-month cruise through deep space. But overall, rover scientists say, the early numbers suggest that astronauts could endure a long-term, roundtrip Mars mission without accumulating a worryingly high dose (though a few big solar eruptions directed toward Mars could complicate things considerably).

Drilling into a Martian rock

In February, Curiosity used its hammering drill to bore 2.5 inches (6.4 centimeters) into a Red Planet outcrop called "John Klein," marking the first time any rover had ever drilled into a rock to collect samples on another world.

Going so deep beneath the Martian surface allowed Curiosity to study the planet's environment as it existed billions of years ago, leading to perhaps the expedition's biggest scientific discovery to date (see below).

A habitable environment

Curiosity spotted some of the key chemical ingredients for life in the gray powder it drilled out of the John Klein rock, including sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and carbon. The fine-grained rock also contained clay minerals, suggesting a long-ago aqueous environment, perhaps a lake, that was neutral in pH and not too salty, researchers said.

With this evidence in hand, the Curiosity team announced in early March that the rover's landing site could have supported microbial life billions of years ago.

"We have found a habitable environment that is so benign and supportive of life that probably, if this water was around and you had been on the planet, you would have been able to drink it," Curiosity chief scientist John Grotzinger, of Caltech in Pasadena, said at the time.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.