Fish Fingers: Your Digits Used to Be Fins

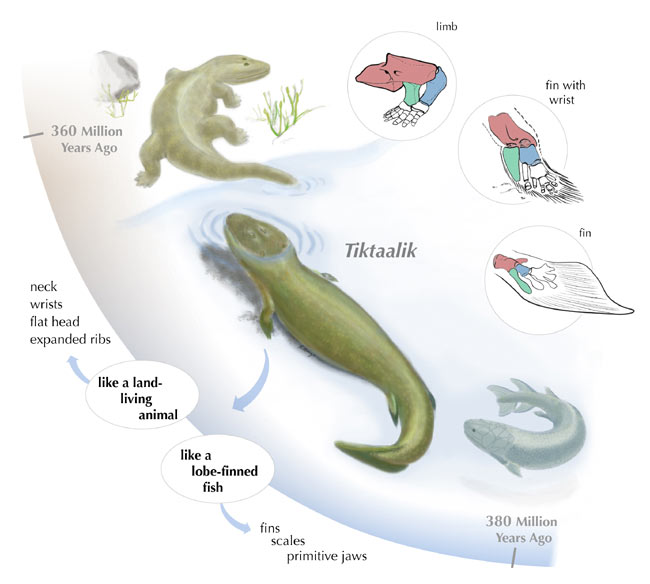

An ancient fish sported something like fingers that were the precursors to our own digits, according to an analysis of a new fossil skeleton. "It's really the last piece of evidence to say fingers are not new. They were really present in fish," said lead researcher Catherine Boisvert, an evolutionary biologist at Uppsala University in Sweden. The fossilized skeleton belonged to Panderichthys, a predatory fish that spanned up to 4 feet (130 cm) and likely dwelled in shallow waters where it inched along the muddy bottom about 385 million years ago. While the fossil was discovered in the 1990s by chance in a brick quarry in Latvia in northern Europe, scientists only recently analyzed the fins with computed tomography (CT) and found that the right paddle is tipped with four bony extensions. If you were to turn back the clocks to the Devonian period when Panderichthys lived and spied the fish, you would not have noticed its "fingers," Boisvert explained. That's because the bony digit precursors were tucked beneath the fin's skin and bony scales and rays. The fan-like array of fingers, however, would have made Panderichthys' paddles broader at the ends. The broad fins would have made for stronger supports for the fish to lean on rather than for all-out swimming. "It was probably using its front fins as supports to be able to look up, kind of doing push-ups at the bottom of the river looking outside with its eyes," Boisvert said, adding that the fish's eyes were on the top of its skull and thus probably good for looking above the mud for fish food. Though Panderichthys was not made for landlubbing, if the need to hop from the water arose, the fish had the means. "So if it was stuck in a pool and it was drying out, [the fish] would have been able to get itself out to the next water body," Boisvert told LiveScience. "It's doing push-ups on land with its big fins and then its pelvic fins (hind fins) are used for an anchor in the mud." Basically, Panderichthys would have dragged its body along land. "It wouldn't have been pretty," she added. The fossil finding, detailed in the Sept. 21 issue of the journal Nature, fills in a gap in the evolution of tetrapods, or four-legged animals. About 380 million years ago, our fishy ancestors crept onto land. Fossil evidence has continued to refine scientists' understanding of this transition, though they still have many questions regarding the fin-to-limb transition and development of other locomotion features. For instance, one such transitional fish called Tiktaalik roseae lived about 375 million years ago and showed signs of both water living and land trekking. However, Boisvert said, even though Tiktaalik is closer evolutionarily to tetrapods, its specimens lack the distinct finger precursors seen on Panderichthys.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.