Circumcision Alters Penis Bacteria

Circumcision changes the bacteria ecosystem of the penis, perhaps explaining why the foreskin-snipping procedure reduces the risk of HIV infection, a new study finds.

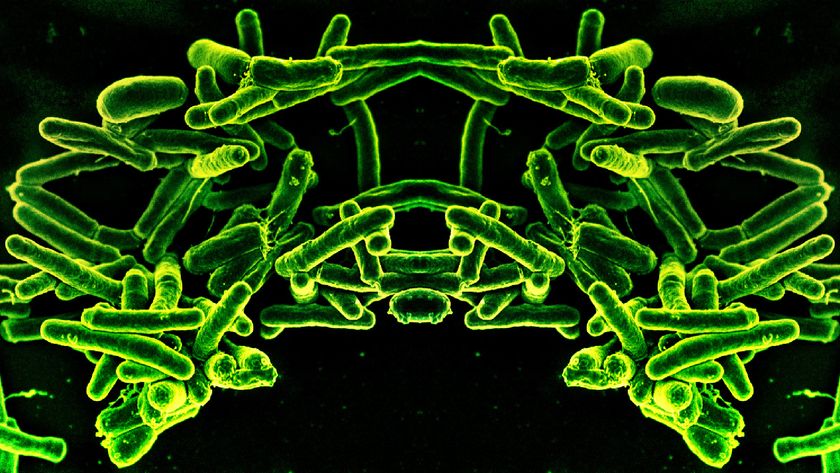

A year after men received circumcisions, the total bacterial load in the area that used to be under the foreskin dropped significantly, researchers report today (April 16) in the journal mBio. Anaerobic bacteria, which thrive in limited oxygen, declined most dramatically. Some aerobic bacteria, which need oxygen to live, increased.

"It's dramatic," study researcher Lance Price, a genetic epidemiologist at George Washington University in Washington, D.C, said in a statement. "From an ecological perspective, it's like rolling back a rock and seeing the ecosystem change." [5 Things You Didn't Know About Circumcision]

Circumcision's effects

Circumcision in the United States is usually done within the first few days of life. It's a controversial procedure, with some scientists and anti-circumcision advocates arguing that the removal of the foreskin reduces sexual sensitivity. Studies on adults who are circumcised later in life have found little to no difference, but many of those men are circumcised for medical reasons, confusing the issue.

Circumcision does carry some health benefits, leading the American Academy of Pediatrics to conclude in 2012 that the benefits outweigh the risks. The organization recommends parents making the decision for their children after discussing it with their pediatricians.

Among the most intriguing benefits of circumcision is the finding that circumcised men are less likely to contract HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. A 2005 study of South African men found that circumcised men who had sex with an HIV-positive woman were 63 percent less likely than uncircumcised men to contract the virus. Circumcision has also been shown to reduce the risk of contracting HPV, or human papillomavirus, which can cause cervical cancer if a man infects his female partners with the virus, and herpes simplex virus type 2, better known as genital herpes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new study of men circumcised as adults in Uganda, Price and his colleagues found less biodiversity in the microbes, or microbiome, living in the now foreskin-free area of the penis. The bacterial die-off may be a good thing, Price said, because some of the species that decline are known to cause inflammation.

Cellular changes

It's possible that the pre-circumcision bacteria activate immune cells in the skin called Langerhans cells, which then respond to HIV by presenting them to the immune system's helper T cells; these helper cells typically coordinate a defensive immune response. Unfortunately, HIV has evolved to thrive and reproduce inside helper T cells, so Langerhans cells that present the virus to the immune system make infection more likely, not less. However, it's still unknown whether Langerhans cells are the culprit behind HIV infection in uncircumcised men. The researchers plan to follow up to explore this possibility.

If they succeed, it won't necessarily mean that every man should get circumcised.

"The work that we're doing, by potentially revealing the underlying biological mechanisms, could reveal alternatives to circumcision that would have the same biological impact," Price said. "In other words, if we find that it's a group of anaerobes that are increasing the risk for HIV, we can find alternative ways to bring down those anaerobes."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.