How the New Bird Flu Virus Evolved

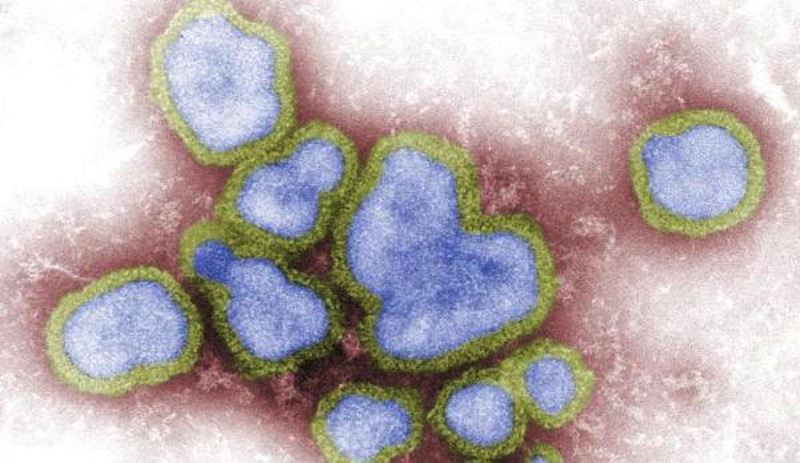

The new bird flu virus evolved from three other influenza viruses, researchers say.

Genes from the three viruses combined in a new way to form the new H7N9 virus, which has so far sickened 60 people in China, 13 of whom have died, according to the latest update from the World Health Organization. There is no evidence that the virus can spread from person to person, but authorities are continuing to monitor people who have been in close contact with those who have become sick.

The details of how the three viruses came together to give rise to the new strain, which has never been seen before in humans, were published by Chinese researchers in a report Thursday (April 11) in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Experts say flu viruses are known to evolve at a particularly fast pace.

"When an organism is infected with more than one flu virus, it's a wild free-for-all, in terms of which chromosomes will combine" into a single new virus, said Dr. Bruce Hirsch, an infectious disease specialist at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, N.Y., who was not involved in the report.

As two viruses reproduce within a single host cell, new viruses are made that contain genes from both of the original viruses, Hirsch explained. Scientists call this process "reassortment."

"It's like shuffling a deck of cards," Hirsch said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Influenza viruses have eight genes. In the new H7N9 virus, only one of those genes came from a previously known H7N9 virus that is commonly found in wild birds. That gene codes for a protein called neuraminidase (which is represented by the "N" in H7N9).

A second gene in the new virus comes from an H7N3 virus often found in ducks, the researchers wrote. This gene codes for a protein called hemagglutinin (the "H" in H7N9). This protein is found on the surface of the virus, and it’s the part of the virus that people infected with the virus make antibodies against, Hirsch said.

Hemagglutinin also explains why people, but not birds, get sick from the new virus — the gene encoding has a mutation that lets the hemagglutinin bind to a sugar molecule found in the lower respiratory tracts of people, but not of birds, Hirsch said.

The remaining six genes of the new strain came from an H9N2 virus commonly found in birds called bramblings, according to the report.

Influenza viruses tend to evolve at a particularly fast pace, Hirsch said. "It's like Darwinian evolution on steroids."

The reassortment that took place and led to the new virus is a little unusual, Hirsch said. Flu viruses usually infect humans only after infecting an intermediate host that is also a mammal, such as a pig. The authors of the new report say the new virus moved directly from birds to humans.

Flu viruses tend to evolve along two different time scales, Hirsch said. There is "genetic drift," which involves the slow accumulation of less-impactful genetic changes, and "genetic shift," which is a sweeping change that results in a virus that is completely different. The reassortment that gave rise to the new virus is an example of genetic shift, he said.

In earlier times, genetic shifts in flu viruses have been linked with large-scale outbreaks. The Spanish flu outbreak of 1918 occurred when a virus shifted from an H3N8 virus to an H1N1 virus. "That was also a reassortment event," Hirsch said. In addition, a shift to an H2N2 virus caused an outbreak in 1957, and a shift to an H3N2 virus caused an outbreak in 1968, he said.

"It has happened again and again. Most of the time, genes reassort into a virus that is not great, but there is no epidemic," Hirsch said. "But when there's a strong, fit virus — and there is no native immunity — that's when outbreaks happen."

He continued, "In a world with more crowding, with lots of activity, there is more potential for viruses to get together, to reassert, to evolve and emerge."

Pass it on: The new bird flu virus evolved from three existing bird-flu viruses.

This story was provided by MyHealthNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Karen Rowan @karenjrowan. Follow MyHealthNewsDaily @MyHealth_MHND, Facebook & Google+.