Exoplanet Atmospheres Reveal 'Peculiar' Fingerprints

The chemical fingerprints of four alien planets have revealed unexpected patterns, new research finds.

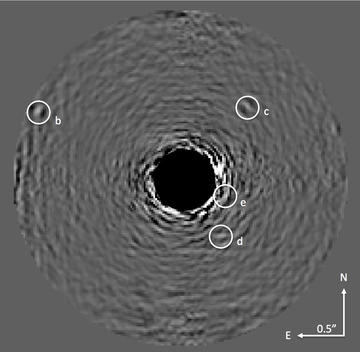

According to SPACE.com, scientists were surprised to find that the chemical compositions of four massive planets 128 light-years away weren't as mixed as expected. At the temperatures of these planets — 1340 degrees Fahrenheit (727 degrees Celsius) — researchers would expect to see atmospheric mixes of ammonia and methane. Instead, each of the four worlds exhibited either ammonia or methane, but not both.

"These warm, red planets are unlike any other known object in our universe," astronomer Ben Oppenheimer, chair of the astrophysics department at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, said in a statement. "All four planets have different spectra, and all four are peculiar. The theorists have a lot of work to do now."

To fingerprint the atmosphere of planets orbiting a distant star, the researchers had to filter out the light of that star, known as HR 8799. They did so using advanced imaging at the Palomar Observatory in California.

The remaining light spectra from the planets showed light-absorption patterns that researchers could translate into ratios of gases in the atmosphere. Chemicals and gases absorb light differently, leaving unique signatures on the spectra.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.