Bureaucracy, Meat Production Crucial To Building Egypt's Pyramids

(ISNS) -- Of the Seven Wonders of the World only one remains standing: the 4,500-year-old pyramids of Giza in Egypt. How an ancient civilization organized the people, the supplies and the infrastructure to put up something that huge and long-lasting remains mostly a mystery and the topic of considerable controversy. Some cable television programs even credit aliens

Archeologist Richard Redding of the Kelsey Museum at the University of Michigan thinks he has worked it out. The effort required industrial farming, cattle drives, and tens of thousands of workers. No Martians.

The best estimates are that some 8,000-10,000 workers at a time labored over 20 years, Redding said. The pyramids were built during the 3rd and 4th dynasties of what archeologists call the Old Kingdom, from 2600-2100 B.C.

They were not slaves, and they were not Hebrews. Hebrews, if they ever were slaves in Egypt -- and there is no archeological evidence they were -- would have come much later.

"They were young males, who ate exceptionally good food and had good medical care and were working for the good of society," Redding said.

It was believed that when a king died (the word "pharaoh" came 1,000 years later) he went to sit alongside the gods and would intervene on behalf of his people, discouraging the gods from sending plagues or skipping the life-giving Nile floods. The pyramids were built to properly prepare the king for that journey, Redding said.

The workers organized themselves into gangs, something like labor unions. Officials would go into the provinces, called nomes, and tell the leaders of the nomes how many workers were needed. Each nome would send a gang.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The gangs were named, Redding said, such as the Drunkards of Menkaure.

Feeding and tending the mass of workers required a bureaucracy of amazing efficiency.

The Egyptians were almost obsessed with keeping records so there is considerable evidence on papyrus on how much bread they ate, but there is very little information that survived on the quantities of meat and the infrastructure that provided the food, which is where Redding's research comes in.

Redding started by calculating the calories or grams of protein the workers would need to do hard labor, using modern statistics. He adjusted for body size -- ancient Egyptians were smaller than modern humans. They needed to eat 67 grams of protein each day, slightly more than what is found in two McDonald's quarter pounders with cheese. If half the workers' protein came from meat, each worker probably ate almost six pounds of meat each week.

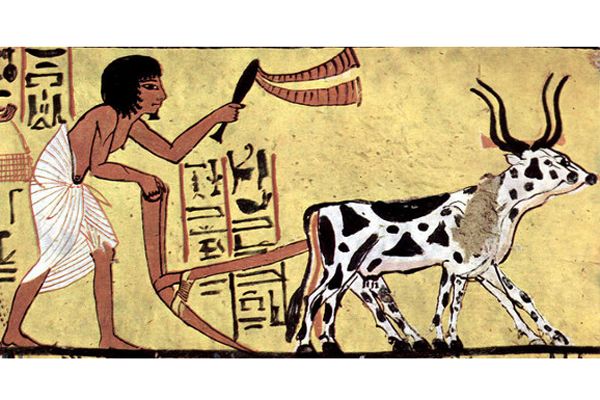

He assumed half the protein came from meat, some from Nile fish. Then, he looked at the breeds of cattle found in ancient Egypt and how much meat one could get from each animal to figure out how many animals would be required to provide the protein.

He said the 10,000 workers at the site he studied in Giza consumed 105 cattle and 368 sheep or goats every 10 days. Herds big enough to supply that many animals would contain an estimated 21,900 cattle and 54,750 sheep or goats, which would have required 640 square miles, about 5 percent of the Nile Delta. It would have required almost 19,000 people to raise that many animals, almost 2 percent of the kingdom's population.

He came to those figures partly by inspecting the bones found at the site--construction gang garbage. He and his colleagues studied 175,000 bones. Half came from cattle, most of the rest from sheep and goats.

How the animals got to Giza is controversial; Redding thinks they came in long cattle drives. Other think they were shipped in on the river.

Every two years, representatives of the central government went into the field and took a census of the cattle, goats and sheep and they reported back to the king's office so the bureaucrats knew exactly what was available and where to provide the food the workers needed, a complex system modern societies need computers to organize.

The workers lived in construction camps, laid out like a city, which included barracks housing 20-40 men and a large administrative center. Food was prepared in central kitchens and distributed. The higher up the administrative chain a person was, the better the food.

"They started off from the very beginning as bureaucratic society and it was very hierarchical," said Egyptologist Jennifer Hellum of the University of Auckland in New Zealand. She thinks Redding's assessment may be correct.

"They had to have that level of sophisticated bureaucracy to build those pyramids. They had a census, taxation, a centralized government that was necessary," she said.

They paid a heavy price. They stopped building pyramids after the 4th dynasty, Hellum said. "They ran out of money."

Redding presented a portion of this research in early April at a meeting of the Society of American Archaeology.

Joel Shurkin is a freelance writer based in Baltimore. He is the author of nine books on science and the history of science, and has taught science journalism at Stanford University, UC Santa Cruz and the University of Alaska Fairbanks

Inside Science News Service is supported by the American Institute of Physics.