Eww! Early Earth Smelled Like Rotten Eggs

Kids like to taunt each other with the cry, "Last one there is a rotten egg!" In Earth's case, that might be more true of the first ones there, according to a new study suggesting that millions of years ago, the planet emanated such a stench.

The research, published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, finds fossil evidence of microbes snacking on other microbes, a form of feeding called heterotrophy. Heterotrophs can't make their own organic nutrients, so they have to eat other life forms. This is in contrast with autotrophs (think plants), which can synthesize their own food from sunlight or inorganic chemicals.

Researchers suspected that organisms have been eating other organisms for a very long time — about 3.5 billion years, said study researcher Martin Brasier, a professor at Oxford University's department of earth sciences. The new study clarifies the process about 1.9 billion years ago. [Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures]

"In this study, for the first time, we identify how it was happening and 'who was eating who,'" Brasier said in a statement. "In fact, we've all experienced modern bacteria feeding this way, as that's where that 'rotten egg' whiff of hydrogen sulfide comes from in a blocked drain."

Early Earth may also have been purple, according to a 2007 study that found that ancient microbes may have shone a purplish hue.

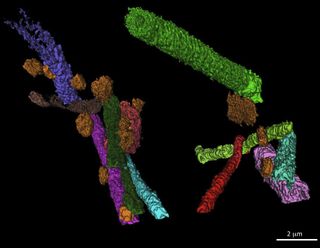

Brasier and his colleagues analyzed fossils of a bacterium called Gunflintia. These fossils measured just 3 to 15 microns in diameter; in comparison, the eye of a needle is about 1,230 microns across. Compared with other bacterial fossils, the tubular outer sheath of Gunflintia were more likely to show perforations, a sign that other bacteria had been snacking on them.

Another clue that early Earth was a bacteria-eat-bacteria world was the discovery of iron sulfide replacing some segments of the Gunflintia sheaths. Iron sulfide, the compound that makes up fool's gold, is a waste product of certain heterotrophic bacteria that breathe sulfate. These sulfate-reducing bacteria, which ultimately produce sulfides, date back 3.5 billion years, according to previously researched fossils.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Whilst the Gunflintia fossils are only about half as old, they confirm that such bacteria were indeed flourishing by 1,900 million years ago," researcher David Wacey, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Western Australia, said in a statement, referring to the fossils from this study. "And that they were also highly particular about what they chose to eat."

The sulfate-breathers may not have been the only ones chowing down. The researchers also found clusters of 1-micron-sized rod and sphere bacteria in the Gunflintia fossils that may have died while in the process of consuming the larger microbes.

Editor's Note: This article was updated at 6pm Eastern Time to correct a typo in the third paragraph. The fossil organisms are 1.9 billion years old, not million.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.