Tongue Erections Help Bats Sop Up Nectar

Bats use erectile tissue to drink. But don't worry — the tissue is on their tongues.

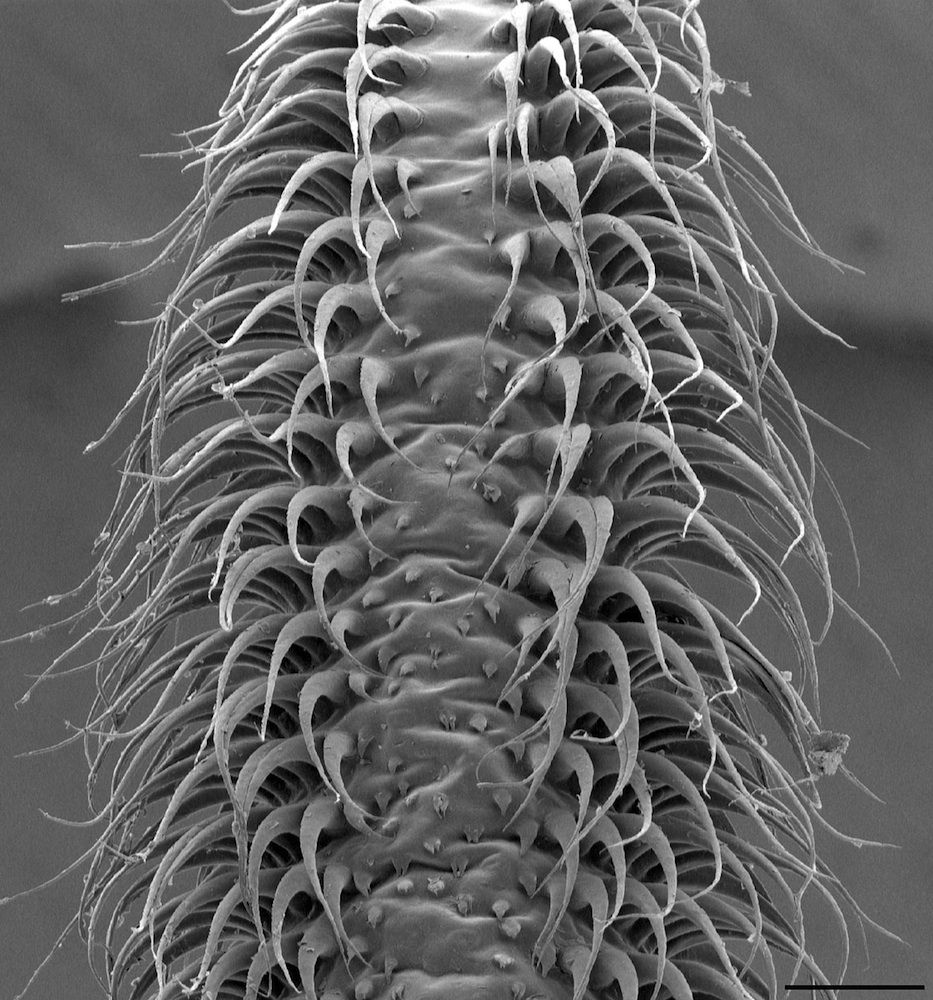

Nectar-eating bats lap up the sweet liquid by engorging their tongues with blood, which, in turn, makes hairlike projections on the tongue stand at attention, new research finds. Together, the erect hairs, called papillae, act like a mop that grabs more liquid than a smooth surface could alone.

Video of the process shows that as the bat reaches out to grab the nectar, its tongue turns bright red as blood automatically rushes in. The discovery is more than simply weird animal trivia, though; researchers think the tongues could be good models for developing kinder, gentler surgical tools. [See Video of the Amazing Erect Bat Tongues]

"These bat tongues are very flexible, and they're soft," said study researcher Cally Harper, a doctoral student at Brown University. "They could be really useful [inspiration] in bending around the curves of blood vessels and intestines, but also, they may minimize damage to some of those soft tissue structures."

Hairy tongues

Scientists have long known that nectar-feeding bats have hairy-looking tongues, as do hummingbirds and other species that rely on flowers for food. These hair projections are called papillae, which are specialized versions of the bumps that dot the tongues of humans and other mammals. Many human papillae host taste buds, but the hairlike papillae on bats show no signs of sensory tissues. (Bats’ taste buds are further back on their tongues.)

Anatomists also have noticed large blood vessels in these bats' tongues, Harper told LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I thought, 'Oh, that's really interesting that there are these enlarged blood vessels and these really specialized papillae,'" Harper said. "There's the possibility that maybe blood flow was used to move these papillae during feeding."

Dissections of bat tongues revealed that there were sinuses, or spaces, along the sides of the tongues that extended into the papillae, suggesting blood flowed through the millimeter-long hairs. Harper and her colleagues just had to find out whether the papillae moved during feeding.

To do so, they set up high-speed video cameras around feeding stations and let the nectar-eating bat Glossophaga soricina have at the sweet spots. Nectar-feeding bats have keen spatial memory and return to the same spots to feed again and again, Harper said.

"All I had to do was make sure my feeder full of sugar water was set up in the same location, and then all I had to do was sit and wait," she said.

Mopping up nectar

At 500 frames per second, the videos showed that as the bats extended their tongues, at first, the papillae were flat against the tongue surface. But then, as the tongue hit its maximum elongation, the hairs became erect. Color video revealed that this change in position occurred as the tongue tip flushed bright red.

"The hairs separate from each other, and that creates a little space between each of the rows of hairs on the tongue," Harper said. "Each one of those spaces becomes filled with nectar."

The process is automatic, and likely driven by muscular tension in the tongue, Harper said. She and her colleagues report their findings today (May 6) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Mammalian penile erections also use blood to create stiffness, with arteries dilating to fill the penis with blood as contracting muscles prevent that blood from draining back to the body.

Bat tongues are just one of many animal features with promise for human engineering. Scientists have studied snail shells to develop stronger body armor, sticky gecko feet to inspire better adhesives, and insects to engineer miniature flying robots.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular