Bones Reveal Oldest Case of TB

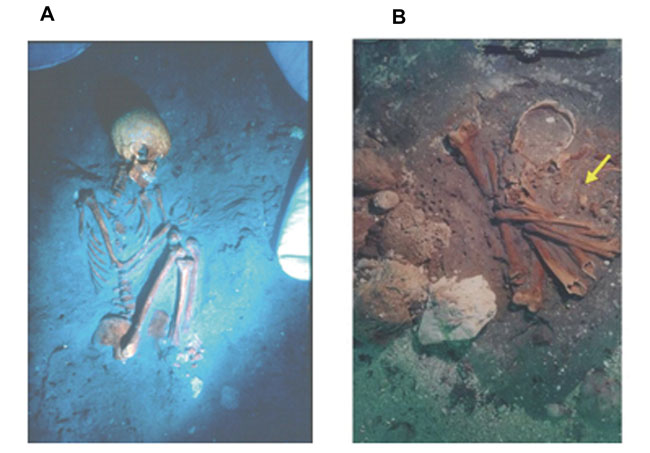

An excavated skeleton of a Neolithic woman and an infant buried with her show signs of tuberculosis, making them the oldest known TB cases confirmed with DNA, researchers announced today.

The 9,000-year-old bones were found submerged about six miles off the coast of Haifa, Israel, in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, where the ancient village of Atlit-Yam once existed. If accurate, the discovery shows that the infectious disease is 3,000 years older than previously thought.

Tuberculosis is and has been a major cause of human death and disease worldwide, although only about 10 percent of all those infected become ill. This high latent infection rate suggests a close relationship between humans and TB throughout history.

TB in humans is caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria and is spread in the air, but another bacteria called Mycobacterium bovis also caused some death by TB in a small subset of humans who caught it from milk, milk products or meat from infected cattle.

There has been ongoing debate about the evolution of these and other bacteria that can cause TB. However, the analysis of the DNA in the Atlit-Yam skeletons confirms a theory that bovine TB evolved later than human TB.

The oldest cases of human TB confirmed by ancient DNA include reports from Ancient Egypt (3500 B.C. to 2650 B.C.) and Neolithic Sweden (3200 B.C. to 2300 B.C.).

There are also less reliable reports, based just on lesions on bones, dating back even earlier, including on a Homo erectus fossil from to 490,000 to 510,000 years ago in Turkey.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One of the earliest cases of TB in Britain, dating to A.D. 302 was reported last month.

The new research is detailed Oct. 15 in the online journal PLoS ONE.

Bone lesions

The remains, found along with tools and bones from goats, cattle, pigs, gazelles, deer and other humans, were submerged for thousands of years. The people who lived at Atlit-Yam were some of the first to make the transition from being hunter-gatherers to being more settled farmers, and the settlement is one of the earliest with evidence of domesticated cattle.

When researcher Israel Hershkovitz of Tel-Aviv University examined the infant and adult woman skeletons (presumed to be the baby’s mother), he noticed the characteristic bone lesions that are signs of TB. The mother and child probably both died of TB.

Helen Donoghue and Mark Spigelman of University College London then analyzed the bones’ DNA as well as fats in the cell walls from M. tuberculosis. The DNA was sufficiently well preserved for molecular typing to be carried out and, combined with the fat findings, confirm infection with the human strain of tuberculosis.

“What is fascinating is that the infecting organism is definitely the human strain of tuberculosis, in contrast to the original theory that human TB evolved from bovine TB after animal domestication,” Donoghue said.

“This gives us the best evidence yet that in a community with domesticated animals but before dairying, the infecting strain was actually the human pathogen,” she said.

The animal bones found at the site show that animals were an important food source, and this probably led to an increase in the human population that helped the TB to be maintained and spread, she said.

Deleted DNA

The DNA for the strain of TB found in the skeletons had lost a particular piece which is characteristic of a common family of strains present in the world today, Donoghue said. “The fact that this deletion had occurred 9,000 years ago gives us a much better idea of the rate of change of the bacterium over time, and indicates an extremely long association with humans,” she said.

The finding also could help improve scientists’ understanding of modern TB and thus allow the development of more effective treatments, Spigelman said.

Colleagues at the University of Birmingham, University of Salford, Israel Antiquities Authority and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem also assisted in the research, which was funded by CARE, MAFCAF, the Dan David Foundation, Leverhulme Trust and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

- Top 10 Mysterious Diseases

- Top 10 Ancient Capitals

- Quiz: Artifact Wars

Robin Lloyd was a senior editor at Space.com and Live Science from 2007 to 2009. She holds a B.A. degree in sociology from Smith College and a Ph.D. and M.A. degree in sociology from the University of California at Santa Barbara. She is currently a freelance science writer based in New York City and a contributing editor at Scientific American, as well as an adjunct professor at New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.