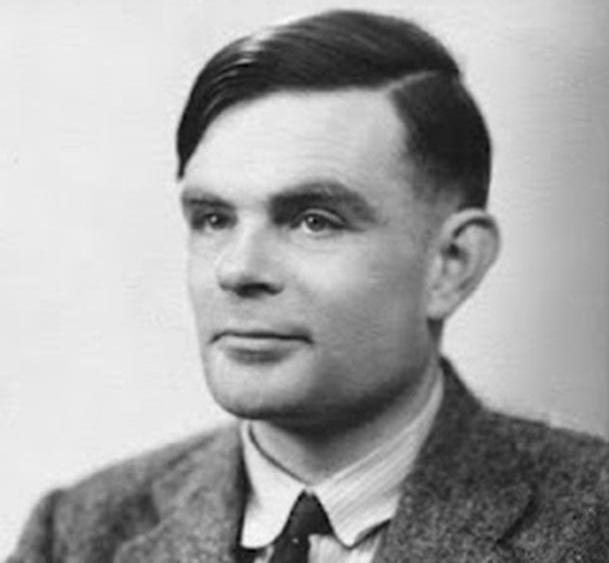

Alan Turing Biography: Computer Pioneer, Gay Icon

Alan Turing was a British scientist and a pioneer in computer science. During World War II, he developed a machine that helped break the German Enigma code. He also laid the groundwork for modern computing and theorized about artificial intelligence.

An openly gay man during a time when homosexual acts were illegal in Britain, Turing committed suicide after begin convicted of "gross indecency" and sentenced to a procedure some call "chemical castration." He has since become a martyred hero of the gay community. In late 2013, nearly 60 years after his death, Queen Elizabeth II formally pardoned him.

Related: History of computers: A brief timeline

Early life

Born on June 23, 1912, Turing was part of an upper-middle-class British family involved in colonial India. Science was a passion for young Turing, who often took part in primitive chemistry experiments. Before applying to schools, Turing was already theorizing on relativity and quantum mechanics.

While attending King's College, Cambridge, Turing focused on his studies, and his passion for probability theory and mathematical logic propelled his career. At the same time, he was also becoming more aware of his identity as a gay man, and his philosophy was becoming closely aligned with the liberal left.

Turing machine

In the years after college, Turing began to consider whether a method or process could be devised that could decide whether a given mathematical assertion was provable. Turing analyzed the methodical process, focusing on logical instructions, the action of the mind, and a machine that could be embodied as a physical form. Turing developed the proof that automatic computation cannot solve all mathematical problems. This concept became known as the Turing machine, which has become the foundation of the modern theory of computation and computability.

Turing took this idea and imagined the possibility of multiple Turing machines, each corresponding to a different method or algorithm. Each algorithm would be written out as a set of instructions in a standard form, and the actual interpretation work would be considered a mechanical process. Thus, each particular Turing machine embodied the algorithm, and a universal Turing machine could do all possible tasks. Essentially, through this theorizing, Turing created the computer: a single machine that can be turned to any well-defined task by being supplied with an algorithm, or a program.

Turing moved to the United States to continue his graduate studies at Princeton. He worked on algebra and number theory, as well as a cipher machine based on electromagnetic relays to multiply binary numbers. He took this research back to England with him, where he secretly worked part time for the British cryptanalytic department. After the British declared war in 1939, Turing took up full-time cryptanalytic work at Bletchley Park.

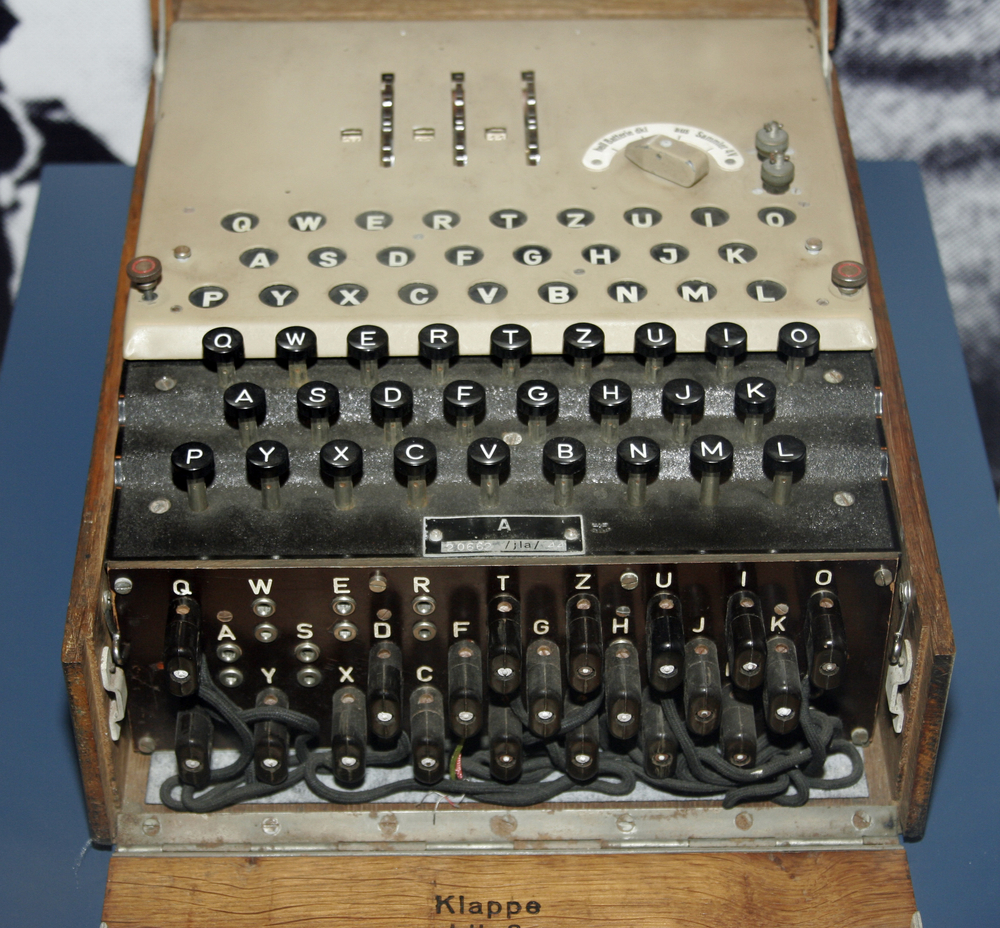

Enigma code

Turing made it his goal to crack the complex Enigma code used in German naval communications, which were generally regarded as unbreakable. Turing cracked the system and regular decryption of German messages began in mid-1941. To maintain progress on code-breaking, Turing introduced the use of electronic technology to gain higher speeds of mechanical working. Turing became an invaluable asset to the Allies, successfully decoding many German messages. [Video: Decoding the Mysterious World of Code-Breakers]

By the end of the war, Turing was the only scientist working on the idea of a universal machine that could plug into the potential speed and reliability of electronic technology. This led to the development of early hardware and the implementation of arithmetical functions by programming, and thus, computer science was born. Turing became well-regarded by the scientific community, as the director of the computing laboratory at Manchester University and an elected fellow of the Royal Society.

Turing test

Turing was also involved in philosophical debates over whether machines could think like a human brain. He devised a test to answer the question. He reasoned that if a computer acted, reacted and interacted like a sentient being, then it was sentient. [Related: What is The Singularity?]

In this simple test, an interrogator in isolation asks questions of another person and a computer. The questioner then must distinguish between the human and the computer based on their replies to his questions. If the computer can "fool" the interrogator, it is intelligent. Today, the Turing Test is at the heart of discussions about artificial intelligence.

Gross indecency

Turing had never been secretive about his homosexuality. He was outspoken and exuberant about his lifestyle, openly taking male lovers. When police discovered his sexual relationship with a young man, he was arrested and came to trial in 1952. Turing never denied or defended his actions, instead asserting that there was nothing wrong with what he did. The courts disagreed, and Turing was convicted of gross indecency. In order to avoid prison, Turing had to agree to undergo a series of estrogen injections. [Countdown: 10 Milestones in Gay Rights History]

He continued his work in quantum physics and in cryptanalytics, but known homosexuals were ineligible for security clearance. Bitter over being turned away from the field he had revolutionized, Turing committed suicide in 1954 by ingesting cyanide.

In 2009, Prime Minister Gordon Brown publicly apologized for how the scientist was treated. And in December 2013, Queen Elizabeth II formally pardoned Turing. A British government statement said, "Turing was an exceptional man with a brilliant mind" who "deserves to be remembered and recognized for his fantastic contribution to the war effort and his legacy to science."

Alan Turing quotes

"We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done."

"I believe that at the end of the century the use of words and general educated opinion will have altered so much that one will be able to speak of machines thinking without expecting to be contradicted."

"Mathematical reasoning may be regarded rather schematically as the exercise of a combination of two facilities, which we may call intuition and ingenuity."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.