The 7 Harshest Environments on Earth

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Intro

Summer heat waves have you clinging to your air conditioner and guzzling ice water? Count your blessings the climate could always be worse.

Here are some of the hottest, coldest and all-around harshest places on Earth.

Greenland

All but the rocky coastline of this island nation is covered in an ice sheet up to 1.8 miles (3 kilometers) thick. If that's not enough of a tip-off that Greenland's name doesn't represent truth in advertising, consider that the northernmost edge of the country is a mere 460 miles (740 km) from the North Pole.

The ice sheet keeps Greenland's population of 57,000 confined to the coastline, where ice gives way to fjords and barren mountains. The northeast quarter of the island, known simply as The National Park, is populated only by polar bears, walruses and other Arctic wildlife. Other than whalers, seal-hunters and the occasional scientist, few humans travel into the Park. The nearest village, Ittoqqortoormiit, sees three months without a sunset every summer, which may help make up for mid-November to mid-January, when the sun never rises over the horizon.

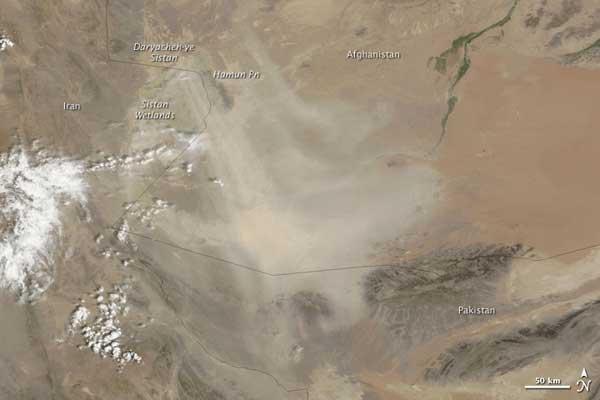

Sistan Basin, Afghanistan

This region along the southern border of Afghanistan is one of the driest in the world, and recent events have made it worse.

Despite its arid climate, the Sistan Basin used to be home to the Hamoun wetlands, an 800-square-mile (2,000-square-km) oasis fed by the Helmand River. The wetlands supported wildlife and human agriculture until the 1990s, when they began to disappear.

The reason was decades of damming and irrigation combined with an unprecedented drought. In 2001, according to NASA's Earth Observatory, precipitation in the Sistan Basin dropped 78 percent. The wetlands dried up and became a dustbowl.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The United Nations is part of an effort to reverse the damage, but war and instability are complicating efforts to return water to the desert.

The Changtang region of the Tibetan Plateau

If the Tibetan Plateau is the Roof of the World, the northern Changtang region is its apex. With an average elevation of 16,400 feet (5,000 meters), this high, dry steppe is punctuated by brackish wetlands. Despite short summers, arctic winters and precipitation that falls mostly as hail, birds, Tibetan gazelle and wild sheep survive in the Changtang.

So do a few hundred thousand people called the Changpa. These nomads move from camp to camp, herding goats and other livestock. But in Changtang and throughout the Tibetan Plateau, grasslands are dying as a result of overgrazing and climate change. The result, according to an April 2010 National Geographic article, is that nomads are forced to move to government resettlement camps, where they face unemployment and water shortages.

Siberia

This vast swath of northern Asia extends from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Arctic Ocean in the north and to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It's perhaps best known for being a place of exile, where Soviet gulags dotted the landscape in the 20th century and political prisoners and religious outcasts were banished in the centuries before.

Today, parts of Siberia boom thanks to oil, gas and mineral discoveries, but the area is as harsh as ever. Temperatures can soar above 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius) in the summer and plummet into double-digit negatives in the winter. The town of Oymyakon in Siberia is the coldest permanently inhabited village in the world, with a record low temperature of minus 90 F (minus 67.7 C) in 1933.

The Australian Outback

Spiders and snakes and crocodiles, oh my! The Australian Outback is home to lots of hostile-sounding wildlife and little else. Arid weather, fierce sun and infertile soil keep the population low in this desert, which spans most of the continent of Australia.

Although the Outback is home to the Inland Taipan, the most venomous land snake in the world (which has never been known to kill humans), and the saltwater crocodile (which has), the greatest danger in the desert is heat. In Alice Springs, a town almost perfectly centered on the continent, summer temperatures reach 113 degrees Fahrenheit (45 degrees Celsius). In this climate, engine trouble or a bogged-down vehicle can turn deadly, which is why travelers are advised to carry spare parts, an emergency radio beacon and lots and lots of water.

The Sahara Desert

With less than 3 inches (7.6 cm) of precipitation each year, the Sahara Desert is one of the driest places on earth. And the temperature is beyond sweltering: The mercury regularly tops out around 122 degrees Fahrenheit (50 degrees Celsius) in summer. The hottest temperature on record, 136 F (58 C), was recorded in the desert town of El Azizia, Libya.

Few humans make the Sahara desert their home. Nomads such as the Tuareg people survive on the Sahara's margins, trading, hunting and raising livestock on sparse vegetation. The central, drier parts of the desert are almost entirely unpopulated.

Antarctica

When it comes to harsh spots, Antarctica sweeps the superlatives: According to the CIA World Factbook, this southern land mass is the coldest, driest, highest and windiest continent. The coldest temperature on Earth was recorded in Antarctica in 1983, when the outside air hit minus 129 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 89 degrees Celsius) at Vostok Research Station, which sits at the center of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, about 800 miles (1,300 km) from the Geographic South Pole.

Antarctica's terrain is 98 percent ice, with the rest made up by barren rock. And while the seas around Antarctica teem with krill, squid, fish and seals, the land is less hospitable. According to the British Antarctic Survey, there are no native reptiles, amphibians or mammals on the continent.

Antarctica isn't completely deserted, though. By the CIA's count, the human population of the fifth-largest continent swells to over 4,000 in the summer as researchers and support crews launch missions from Antarctic research stations. In the winter, about 1,000 people remain to brave temperatures as low as minus 94 F (minus 70 C).

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus