How Amazon Rainforests Outlast Drought: Maybe It's in the Roots

Thick-canopied swaths of the Amazon forest can tolerate seasonal droughts better than many other types of vegetation thanks to their deep roots, a new study suggests.

Previous studies of the Amazon's drought response offered apparently conflicting findings.

Studying the Amazon during a range of climate conditions is important because drought interferes with how tropical forests grow and make new leaves, and ultimately how they cycle carbon into the atmosphere. The study's authors warned that droughts may become more frequent and severe in the coming decades as greenhouse gases build up in the atmosphere.

Satellite-based studies have suggested that Amazon forests green up during droughts because of increased sunlight. Prolonged sunlight during a drought, however, also can increase tree death.

The new study did not find any evidence for sunlight creating a green boost, said study team member Paulo Brando of the Environmental Research Institute of the Amazon, in Brazil.

The team's work, detailed in the Aug. 2 online edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that these dense patches of Amazon forest instead rely on their long roots to tap what little water remains in the soil during a seasonal drought.

A lack of water in the soil could synchronize the budding of new leaves, offering a possible explanation to why scientists see a spike of green during a drought.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A similar mechanism may help areas withstand drought outside of the central Amazon, where the study took place, the study suggests.

"Our study builds on field studies and remote sensing studies to demonstrate that relatively undisturbed Amazon forests are quite tolerant of seasonal drought, unlike other types of vegetation and severely disturbed forests," Brando said.

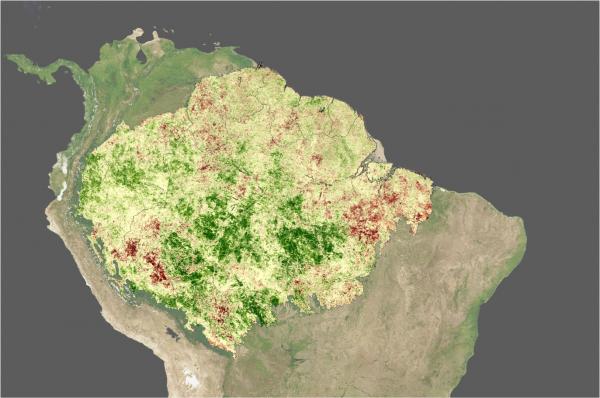

The study used a combination of satellite data from the 2000-08 dry seasons in the Amazon Basin and field data recorded at 280 meteorological stations from 1996 to 2005.

"This analysis is unique in that it captures in great detail how forest productivity varies with meteorological measurements, particularly during drought years," said ecologist Scott Goetz of the Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts. "Our findings build upon earlier work but take those several steps further by actually making the link with climate and examining how forests respond by flushing new leaves."

The study's authors said more work will be required to learn how the Amazon region would respond to longer droughts.

"We see these dense forests are fairly resistant to drought in terms of their greenness, but if drought lasts multiple years, that could change," Goetz said. "The cumulative effects of drought can be much more dramatic."