Typhoons Bury Carbon in Oceans

The torrential rains of a single typhoon can bury tons of carbon in the ocean, two new studies suggest.

It's Nature's way of healing itself.

The findings help determine how much carbon that big storms have historically taken from the atmosphere and buried for thousands of years beneath the sea. And more carbon could be buried by these storms if global warming increases their intensity and frequency, as some scientists have predicted. Scientists have been looking at ways to store carbon to lower the levels of carbon dioxide building up in Earth's atmosphere.

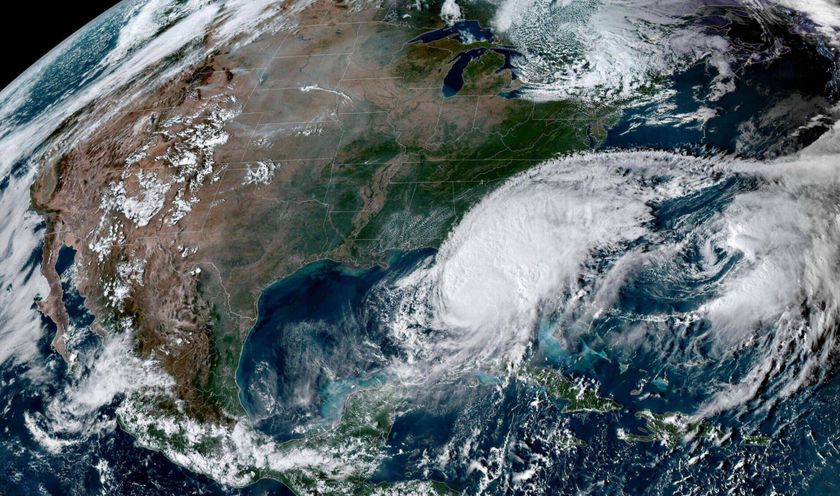

Scientists have long suspected that hurricanes and typhoons (along with cyclones and tropical depressions, these are all versions of storm systems called tropical cyclones) can cleanse the environment of a lot of carbon, because their rains sweep soil and plant material into rivers and then out to sea. This effect is particularly significant for mountainous islands prone to frequent hits from tropical cyclones.

Two different groups of researchers took samples of the sediment in rushing river waters on Taiwan during Typhoon Mindulle, which hit the island in July 2004. One group, whose findings are detailed in the Oct. 19 issue of the journal Nature Geoscience, took sediment samples from the LiWu River, while the other group, whose work is detailed in the June 2008 issue of the journal Geology, sampled the Chosui River.

The Nature Geoscience study, funded by The Cambridge Trusts and the UK National Environmental Research Council, found that 80 to 90 percent of the organic carbon (in the form of soil and plants) eroded by the storms around the LiWu were transported along the river to the ocean.

By dangling one-liter plastic bottles over the Chosui River during the typhoon, the researchers of the Geology study found that 61 million tons of sediment washed out to sea from the river. The amount of carbon contained in that sediment is about 95 percent as much as the river transports during normal rains over the entire year. That works out to more than 400 tons of carbon washing away during the storm for each square mile of the watershed, the researchers reported. Their work was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The carbon in the soil and plants came from carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. When the storm washes the sediment out to sea, it can sink down to the deep ocean, where it will eventually compact and form rocks that can store that carbon for millions of years.

And if typhoons and hurricanes do become more intense or frequent, as some models have indicated, the burial of carbon in the ocean from storm runoff could counteract some part of the warming, by locking the carbon away in the deep ocean, the researchers of the Nature Geoscience study said.

But typhoon runoff is not a cure-all for the carbon dioxide that's been building up in the Earth's atmosphere. Not enough carbon is washed down either as plant material and soil or by chemical weathering of rocks (where carbon dioxide and water disintegrate rock) to get rid of all the extra carbon dioxide that has built up in the atmosphere.

"You'd have to weather [and erode] all the volcanic rocks in the world to reduce the CO2 back to pre-industrial times," said Anne Carey of Ohio State University and a member of the Geology study team.

Understanding how typhoon runoff fits into the Earth's carbon cycle could help sharpen climate change models, though.

- The World's Weirdest Weather

- Top 10 Surprising Results of Global Warming

- What is a Carbon Sink?

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.