Ocean's Color Can Re-Route Hurricanes

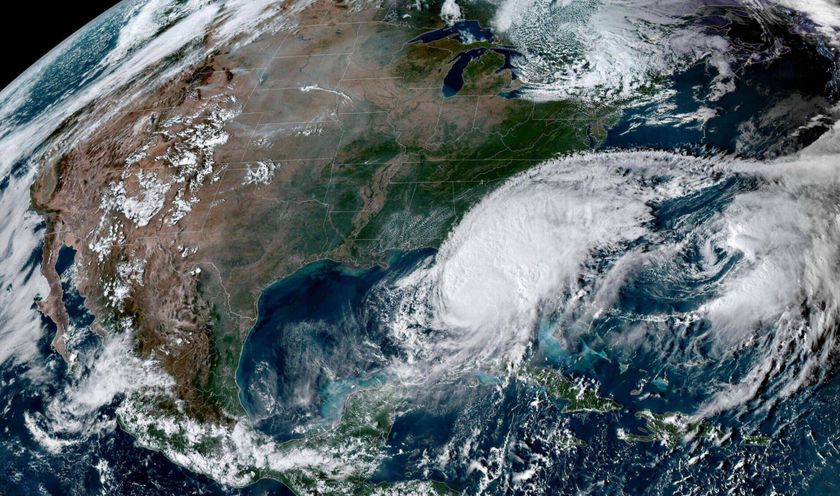

The color of the ocean affects the formation of hurricanes, according to new research. Data indicate that if the waters of the northern Pacific become more blue, tropical cyclone patterns will make a dramatic shift southward.

The new study focused on a vast, relatively empty region of ocean called the North Pacific gyre, which produces about 40 percent of the planet's tropical cyclones. ("Tropical cyclones" are the generic name for typhoons, hurricanes and tropical storms.)

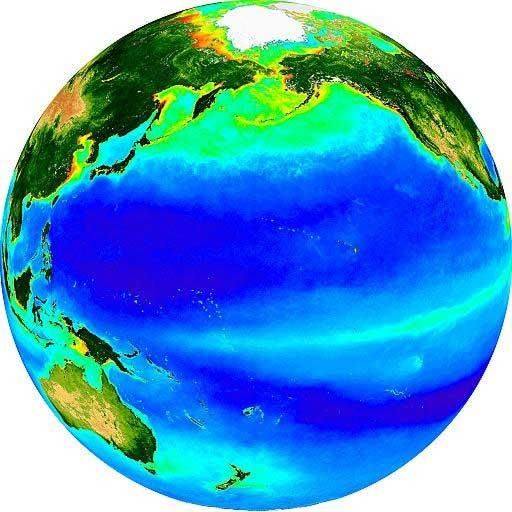

Anand Gnanadesikan, lead researcher in the study, said the dramatic change would stem from a rather un-dramatic source: phytoplankton, the microscopic plants that blanket the Earth's oceans. These ubiquitous, chlorophyll-producing organisms lend the seas a greenish hue, explained Gnanadesikan, an oceanographer with Princeton University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The layer of green acts as a heat sink, trapping the sun's rays and raising the temperature of phytoplankton-filled waters. "Changing ocean color would change the distribution of solar heating," Gnanadesikan said.

A loss of the green means lower surface water temperatures, and a reduction in water temperature affects storm formation .

Gnanadesikan and his team employed complex computer models to reach their conclusions, which he said were certainly unexpected. In one scenario, researchers looked at what would happen if all phytoplankton disappeared from the region. In that case, hurricanes dropped by 70 percent in the area's subtropical regions, but increased by 20 percent closer to the equator.

Hurricanes form primarily over warm tropical waters, which fuel the fledgling storms.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Such extreme changes in phytoplankton levels may not be far-fetched. Some recent research indicates global populations of the tiny green plants have declined over the past century and continue to drop.

Gnanadesikan said that while no model is perfect, theirs performed impressively with the data. "When you look at the patterns that emerge, they're quite realistic in most places," Gnanadesikan told OurAmazingPlanet. "If you put a picture of the winds produced in these models next to a picture of observed winds and stood at the back of the room, you probably wouldn't be able to tell the difference."

Gnanadesikan said scientists have long known that physics affects living things but have wondered if it works the other way if biology affected physics. This new study would seem to indicate nature is capable of working in both directions.

"We are constantly discovering in recent decades how biological activity interacts with climate much more strongly than we thought," said study co-author Kerry Emanuel, a professor of atmospheric science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "This is just another way that we've discovered a link between biology and climate."

Emanuel cautioned that it's too soon to draw conclusions from the data. "It's very interesting that climate seems to respond to this," he said. "What it means for us is very secondary, and we're very far from being able to answer that practical question yet."

Gnanadesikan said that although these projected weather effects are most likely to occur only after about a decade of phytoplankton reduction, the main message of the study remains the same, regardless of the time scale.

"The fact that the oceans are alive helps determine the number of hurricanes," Gnanadesikan said, "and this is not a small effect, this is a big effect."

The study is to be published in a forthcoming issue of the journal Geophysical Research Letters.