Microscopic Creatures Win Ocean Diversity Game

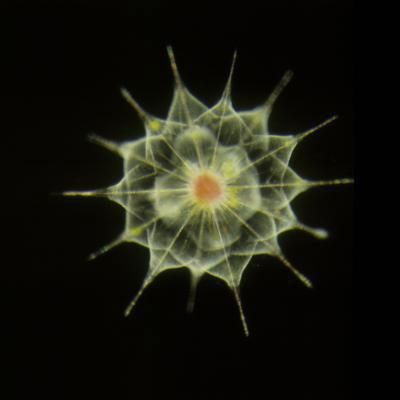

The seas are teeming with a rich diversity of life, much of which is invisible to the naked eye, according to the first worldwide marine census ever conducted.

As many as a billion types of microbes live in the world's ocean , the census found, meaning these microscopic beasties are 100 times more diverse than marine plants and animals. About 38,000 varieties of microbes inhabit just one liter of sea water.

The findings were announced this week at the formal conclusion of the Census of Marine Life , a decade-long, $650 million project involving scientists from 80 different countries.

Most of the Earth's biodiversity is microbial in nature, particularly in the oceans. For more than three billion years, these creatures have mediated critical processes that shape the planet's habitability.

Over the last six years, the International Census of Marine Microbes (ICoMM), a research project of the larger Census of Marine Life , amassed more than 25 million genetic sequences from microbes that swim in 1,200 sites around the Earth.

Researchers gathered samples from polar bays to tropical seas; from estuaries to offshore ; from corals, sponges and whale carcasses; from surface waters to deep-sea smokers.

In 2006, ICoMM scientists made the startling discovery that while a few microbial species dominate the oceans, most species are very low in abundance.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Early on, ICoMM scientists made the crucial decision to collect not just genetic data on the microbes (which would separate them by type), but also contextual information on where they were found latitude and longitude, ocean depth, water pH, salinity, and other conditions.

What they found is that all microbes are not everywhere. Despite an ability to disperse widely in the oceans, the scientists discovered that characteristic microbial communities can define different water masses in the ocean and can tell us about the health of different ecosystems.

"Believe it or not, this is unique, this coupling of (genetic) diversity data and contextual data," said Linda Amaral Zettler, an assistant scientist at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., and an ICoMM program manager.

"The big payoff," Amaral Zettler said, "is it lets the researchers ask ecological questions about microbial populations that otherwise could not be posed."