Serengeti of the Sea: Ocean Predator Study Reveals Surprises

Whither do the great animals of the ocean wander? And when? Thanks to high-tech gadgetry and a decade of work, an answer has begun to emerge one that has revealed two vast "grasslands" of the Pacific Ocean that rival the Serengeti in the riotous diversity of species that converge there, scientists say.

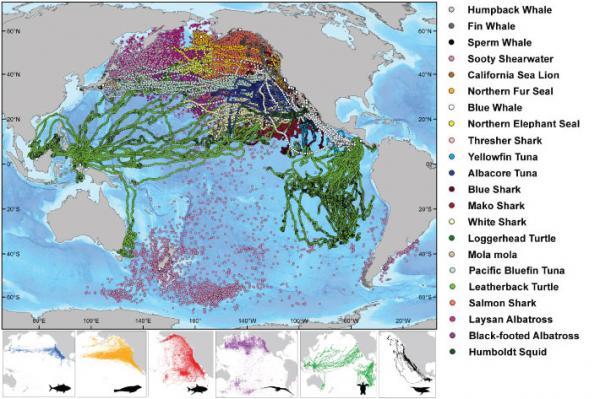

In the largest study of its kind ever attempted, scientists affixed tracking tags to 23 of the ocean's top predators and spied on their whereabouts sometimes within a few meters accuracy and in real time over the course of 10 years.

The Tagging of Pacific Predators Project (TOPP) kicked off in 2000, and published its findings this week in the journal Nature. The project is part of the Census of Marine Life, an ambitious 10-year, multinational effort to assess the state of the planet's oceans, which contain more than 90 percent of the living space on Earth and are still largely unexplored. [Gallery: Amazing Creatures from the Census of Marine Life ]

Sea lions and tunas and birds, oh my!

Though the name "predator" may call to mind toothy monsters several shark species were certainly included the project tracked predators large and small, gentle and ferocious, from tiny birds to elephant seals to blue whales. Any animal that eats another animal.

What emerged was a symphonic portrait of how animals use the ocean, one that revealed a sometimes day-to-day snapshot of where Humboldt squid converged in the deep, where albatross wheeled through the air and where massive leatherback turtles stood in their trans-ocean journeys.

"There have been a number of, 'Oh, wow,' moments," said Dan Costa, a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and one of the study's co-founders. One such moment came five years ago, when the researchers plotted all the species' tracking data together in one spot for the first time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It was like, 'Oh my god, this is incredible. This is working,'" Costa said.

Tag team

Over the course of the project, biologists deployed 4,306 tags upon 1,791 animals, and recorded data from 2000 to 2009. Researchers tracked most animals for under a year, but some salmon sharks provided data for up to 3.5 years.

The scientists used several different kinds of tags that deliver data in different ways. A species' tag was dictated by habits and habitat. Birds and sharks, for example, require different sorts of tag technology. [In Images: Tagging and Tracking Sea Turtles ]

Some tags regularly converse with a satellite, and provide data in real time, allowing researchers to literally check in on an animal day or night. However, for such tags to work, they must occasionally break the surface of the water. Mako sharks, salmon sharks and blue sharks wore these sorts of tags on their dorsal fins, said Randy Kochevar, one of the principle investigators on the project.

Other real-time tags were literally epoxied onto elephant seals. Once the seals shed their fur which they do all at once, in what is termed a "catastrophic molt" they left behind the tags as well, allowing researchers to simply walk along the coast and pick up the discarded tags.

"When we get the tags back, we can get a whole bunch more data back than is relayed to the satellite," Kochevar said.

Other tags detach from an animal at an appointed time and float to the surface of the ocean, delivering months of data to a satellite in one fell swoop. Those were used on great white sharks.

Still other tags were retrieved from animals and sent back to labs, where scientists could download six months of data. This class of tags was surgically implanted into albacore, yellowfin and bluefin tunas, all carefully labeled with "If found, return to TOPP," information. An enclosed promise of a check for $1,000 provided a healthy incentive to fishermen who caught the tracked fish to drop the tags in the mail.

Similar tags were attached to birds tiny shearwaters and huge albatross. Researchers simply recaptured the birds and retrieved the tags, since the animals returned to the same places year after year.

"What we found that was pretty striking is that many of these animals home right back to where we tagged them," said Barbara Block, co-founder of the study and a professor at Stanford University. "They literally live in our neighborhood."

Ocean safari

In fact, Block said, tracking data revealed that most of the 23 species studied in the project converge just off the west coast of North America in a massive swath of ocean called the California Current , which stretches from Canada all the way down to Mexico. The current begins about 3 miles (5 kilometers) offshore and stretches as far as 100 miles (160 km) out to sea.

"It's almost like a giant Yellowstone Park, a place that's full of top predators, everything from blue whales to salmon sharks to white sharks," Block said.

Researchers were able to link animal movements to sea surface temperatures, and found that predators large and small headed to the California Current when waters warmed, likely drawn by rich blooms of phytoplankton, the microscopic plants that form the base of the ocean food chain .

"These are the areas of the ocean that are most productive," Costa said. The movement of the water kicks up nutrients from the cold ocean depths.

In addition to the California Current, the project uncovered a trans-ocean highway between Japan and the vicinity of San Francisco: the North Pacific Transition Zone, another hotspot for iconic ocean creatures. Researchers compared these ocean highways to Africa's lush Serengeti plain, across which thousands of land animals migrate each year one of the greatest migrations on Earth .

"These currents create the grasslands the verdant valleys of the oceans," Costa said.

Block said that it was the advent of new technology that allowed for the research, and said there is still much to be learned about how animals traverse the planet's oceans.

"We've come into the largest ecosystem on Earth , and we've begun to make sense of how animals use it," Block said. "How animals use the space together, where there might be a watering hole and what areas need to be protected."

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain.