Magnetic Signposts Trace Wanderings of Ancient Continents

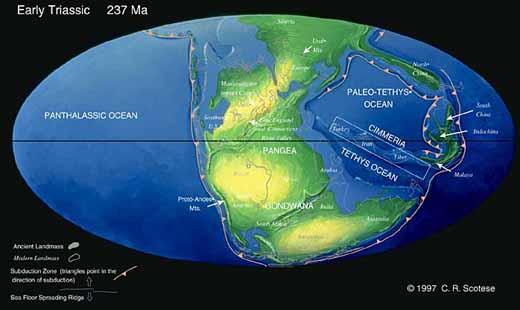

Some 250 million years ago, the Earth's only landmass was a giant continent called Pangaea.

The southern half of this massive chunk of land was called Gondwana, which eventually split into what are today most of the continents in the Southern Hemisphere, as well as a few in the northern half of the globe. Understanding how these bits of land once fit together helps us better understand how the Earth has changed in the past, impacting the life that dwells on it, and how it might change in the future.

But there's one problem in fitting together this paleo-puzzle: The magnetic record, captured in rocks in the Southern Hemisphere, doesn't seem to fit with the magnetic records found in the Northern Hemisphere. All the records should match, as they were once part of the same giant Pangaea landmass.

"Paleomagnetically, the story didn't seem to work," said Mathew Domeier, a geology graduate student at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and an author of a new study looking into this mismatch.

"We guessed that part of the problem was with the earlier data sets from Gondwana, so we wanted to go back and collect some new samples," Domeier told OurAmazingPlanet.

Old vs. new

Double-checking the reliability of this old data was key, because if it was right, maps of the ancient supercontinents would have to be redrawn.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"If you take the older data at face value, you will come up with a drastically different paleogeographic model, and a major continental reconfiguration event becomes necessary in the evolution of the supercontinent," Domeier said.

The team started their sleuthing into the magnetic mystery by drilling out samples from the Sierra Chica, a band of ancient volcanic rocks in central Argentina. Within the tiny cores were magnetic minerals that the scientists used to calculate the location of the magnetic pole 263 million years ago.

"We know how these cores were oriented in the rock, and they act like weak fossil magnets, so we can use them to understand what the magnetic field looked like at that place and time," Domeier explained.

Because the Earth's magnetic poles drift only slightly over time and have well-known reversal episodes (where the north and south poles switch positions), deviations in the location of the calculated pole from the present show how the rocks have moved since the lava cooled. Changes in the paleopole drawn from samples of different ages from the same plate give a map for the plate's movement.

What Domeier and his colleagues found was a picture much closer to the conventional view of the wanderings of Gondwana . The new paleomagnetic pole from Gondwana was found to be in closer accord with those from the Northern Hemisphere, supporting the argument that the apparent difference is perhaps a long-lived data artifact. This means that the conventional model of Pangaea probably doesn't need to be scrapped for a new model of the data.

Clearing up confusion

So why the apparent scientific confusion? Some of the older studies were carried out 30 to 40 years ago, when technology was not as advanced. One problem with rocks is that they aren't ideal magnetic record-keepers, Domeier said.

"You actually can have a record of today's magnetic field superimposed over the older magnetization," he explained. Some of the older studies didn't have the technology to demagnetize or erase the newer impressions, leaving only the oldest recordings.

For now, Domeier says the team is excited that their data lines up with the expectations of the conventional continental reconstruction. "Most of the time people get press for doing something revolutionary, but in this case we're saving the traditional model," he said.

The team plans to continue working to reconcile the differences between Northern and Southern Hemisphere data to create a clearer picture of the paleogeography of Pangaea.