Tsunami Survivors: We Didn't Understand the Threat

By talking with survivors of the devastating tsunami that hit Japan earlier this year, scientists may now have a better idea as to how to help prevent fatalities from such events in the future.

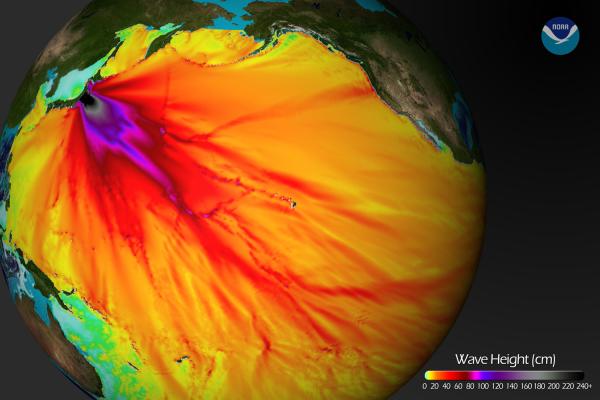

The catastrophic magnitude 9.0 quake that hit Japan in March killed 19,508 people. The resulting tsunami reached heights of up to 100 feet (30 meters) along the coast of northeastern Japan.

In the 115 years before the disaster, a trio of tsunamis hit the region, with one causing 22,000 deaths. In response, many efforts were undertaken to protect against further tsunamis, such as numerous breakwaters — that is, coastal barriers — as well as annual tsunami evacuation drills. Still, the March tsunami claimed many lives, causing up to about 20 percent of deaths from the quake in some areas, said researcher Masataka Ando, a seismologist at Academia Sinica in Taipei, Taiwan.

To understand why the waves killed so many people despite the precautions, researchers interviewed 112 survivors at public evacuation shelters in six cities in Japan in April and June. The aim was to see why many did not immediately evacuate areas endangered by the tsunami.

Underestimated risks, inaccurate warnings

One major problem facing the local population was that scientists underestimated the earthquake and tsunami hazards that northeastern Japan faced. As such, many evacuation shelters lay within areas endangered by the tsunami, and some people were swept away with the shelters.

In addition, many residents did not receive accurate tsunami warnings. The quake destroyed power networks, meaning that many in northeastern Japan did not receive updates telling them of higher waves.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Also, officials issued 16 tsunami alerts in the previous four years before the March quake, but interviewees had only experienced small or negligible tsunamis. The combination of frequent warnings with overestimated waves led to complacency. Complacency "is one of the most difficult issues with infrequent super disasters," Ando told OurAmazingPlanet. All in all, perhaps 10 percent of interviewees did not even think a tsunami would come.

Half of local residents above 55 years of age also experienced the tsunami generated by the 9.5-magnitude 1960 Chile earthquake, the largest earthquake ever recorded. Though that tsunami swept all the way across the Pacific to Japan and killed several people, it was significantly smaller and less deadly than the one this year. This led to a sense that the March tsunami would also be small, the researchers found.

Moreover, some inhabitants assumed the breakwaters would be high enough at 8 to 20 feet (2.5 to 6 m) to protect them. Some thought that with breakwaters only slight flooding would occur, and that moving to the second floor at home was enough.

Improvement needed

Many interviewees did not understand how tsunamis are generated, nor did they understand the need to evacuate to safer areas immediately after hearing about the tsunami. Had they known, they might have evacuated to safer highlands right after feeling strong shaking, researchers noted.

"About two-thirds of the interviewees did not realize that a large tsunami would have struck them 30 to 40 minutes after the strong shaking stopped," Ando said.

Still, the aftermath wasn't as bad as it might've been given different timing. [Images: Japan Earthquake & Tsunami]

"The earthquake was devastating, but it was still very lucky that it occurred during the day," Ando noted. The night after the earthquake, snow and sleet fell on impacted areas — given the power blackout, navigating the streets and hills at night would have been extremely difficult.

Altogether, these findings suggest that current technology and earthquake science need to improve to better estimate tsunami effects and create better safeguards and warning systems. However, teaching residents more about how tsunamis work might help save lives as well, Ando said.

Ando and his colleagues detailed their findings in the Nov. 15 issue of the journal Eos.