Mysterious Lightning Caught in High-Speed, 3D Video

Mysterious "sprites" and "elves" dance high in the Earth's atmosphere — but these aren't mythical creatures, they're disks, globes and tendrils of light caused by lightning.

Now scientists for the first time have 3D images of these enigmas, which could shed light on their origins and whether they influence the planet's climate.

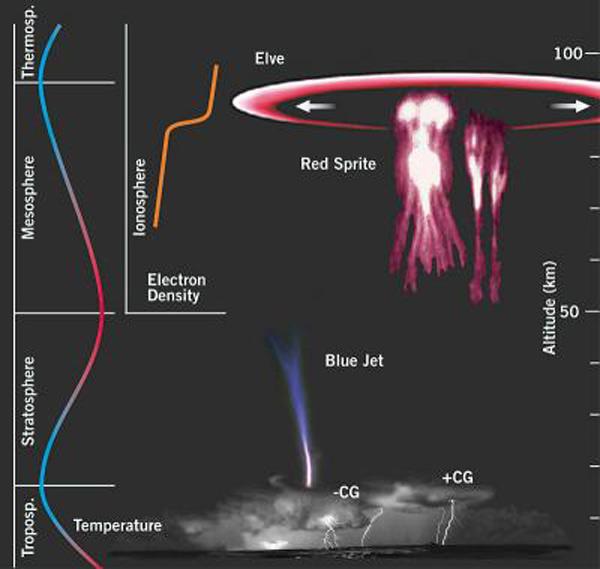

Sprites and elves are both reddish, ultra-fast bursts of electricity bright enough to see during the daytime. Sprites are jellyfish-shaped, starting as balls of light that stream downward, while elves are ring-shaped halos. They are born near the edge of space, high above clouds at altitudes of about 50 miles (80 kilometers).

Scientists first captured images of sprites and elves dancing above thunderstorms in the late '80s and early '90s. Pilots actually saw them decades earlier, but since they flicker in and out of existence so quickly, "no pilot was willing to acknowledge seeing them up there until then, since they thought it'd cast doubt on their mental state," said researcher Hans Stenbaek-Nielsen of the University of Alaska at Fairbanks. "If you blink, you don't see them... they last on the order of 10 milliseconds."

Now, with a pair of jet airplanes, scientists have recorded high-speed, 3D images of sprites and elves. [See the video here.]

"We have one of the best shots of sprites in the world," said researcher Yukihiro Takahashi, of Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan, who presented the research yesterday (Dec. 5) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Up in the sky

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The planes flew out of Colorado from June 27 to July 10, ranging over the western United States at altitudes of about 45,000 feet (13,700 meters). Collaborators on the ground let them know where thunderstorms might be popping up across the country.

The aircraft were separated by a distance of about 12 miles (20 km), recording the enigmas from a distance of about 180 miles (300 km) at high-speed video rates of 10,000 frames per second. The aim was to watch them from two different angles to create 3D images, just as we see the world in three dimensions using two eyes. The resulting pictures make the lights "look like they are at arm's length," Stenbaek-Nielsen said.

The scientists hope a better understanding of the three-dimensional structure of these enigmas could shed light on how they form.

"We still don't know why sprites have so many streamer structures," Takahashi said.

Lightning connection

The leading culprit thought to cause elves and sprites is positively charged lightning, which accounts for about 10 percent of all lightning striking the ground. Since this lightning drains the clouds of positive charge, "the clouds end up negatively charged," said researcher Matthew McHarg, director of the Space Physics and Atmospheric Research Center at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado.

This negative charge in the clouds leads an electric field to build up between them and the upper atmospheric layer above them known as the ionosphere. When this electric field gets strong enough, sprites and elves apparently occur. Images reveal that elves come first, then a ring-like halo structure, followed by sprites, although sprites were also seen forming without either haloes or elves.

It remains uncertain what the importance of sprites is, Stenbaek-Nielsen said. "Are they just like the rainbow — pretty to look at, but no further significance?"

Heated debate

There is much heated debate as to whether sprites and elves connect space weather impacting the upper atmosphere with the lower atmosphere we are most familiar with. For instance, sprites and elves might have chemical effects, influencing climate by generating compounds such as nitrous oxides. "In that case, they would have an effect on the ozone layer, and then directly on the climate and the environment," Stenbaek-Nielsen said.

In the future, the researchers would like to record sprites with even higher-speed video of about 35,000 frames per second. "That way we can see the streamer tips divide and perhaps learn what makes them divide," McHarg said. "We could see new physics."

The ends of the streamers of sprites can divide into up-to-eight-to-10 branches, Stenbaek-Nielsen said. In comparison, lab experiments mimicking such electric bursts only get two or three splittings. Power companies are especially curious about electric discharges, he added — these outbursts can affect their equipment and personnel.

"At high altitudes of 75-to-80 kilometers (45-to-50 miles), the pressure is much reduced," McHarg told OurAmazingPlanet. "The question is, when you change the pressure from what it is on the ground to what it is up there, what happens with how lightning splits? We're still trying to find out."