Up the Backbone: Yellowstone to Yukon

Yellowstone to Yukon

The wind hits me in gusts so hard I must brace myself and scramble to take shelter behind nearby boulders. Dazed and numb, I'm amazed to see tiny blips of color all around me. Strangely beautiful wildflowers grasp the talus rock slopes wringing life from the most harsh of environments.

I've been hiking for almost a month along the spine of the Rockies through the Yellowstone to Yukon region of North America, affectionately dubbed the Y2Y. Stretching over 1,988 miles (3,200 kilometers) from Yellowstone to the Yukon and bordered by five U.S. states and two Canadian provinces and territories, the Y2Y landscape is one of the world's last great bastions of wilderness and a refuge to wild creatures.

The intact geographic and biological diversity of this landscape is also a buffer for species to migrate across in response to climate change. This makes conservation of the Y2Y our best hope for healthy North American wildlife populations in the future.

Native America

The booming grows louder and the throb of dancers pouring into the hall seems to swell with the deep tempo of the drums. Suddenly, pealing calls and deep chants electrify the air as the dancers begin to whirl and sway in patterns of color and motion, both fierce and beautiful.

I'm here at the annual pow-wow in Arlee, Mont., hosted every year by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation. Gatherings, or pow-wows, like these have been a part of indigenous culture in the Rockies since ancient times. Today pow-wows are still gathering grounds to converse and trade, learn and share between tribal groups that share deep ties to this landscape. The arrival of Europeans irrevocably altered Native America, but in some places, like here at the Flathead, native culture is being revitalized through language schools and youth organizations passing on pride and traditions to the next generation.

The Y2Y region of the Rockies is the traditional homeland to many indigenous peoples including the Arapaho, Blackfoot, Crow, Flathead, Shoshone and many more. The art and culture of Native America can be seen on rock walls in the Rockies dating back 5,400 to 5,800 years, as well as in the elaborate living dances and traditions throughout the Rockies today.

Up in the Backbone

The Blackfoot Tribes referred to the Rockies as "the great backbone of the world." Pushing over yet another high pass in the Y2Y, I can't help but agree as I gaze at the vast slabs of rock that jut out like vertebrate over this immense landscape, like the giant columnar backbone of the continent.

The geologic forces that created this masterpiece of rocky cordilleras are both ancient and complex. The U-shaped valleys I hike through are the imprint of the last ice ages when vast glaciers expanded and receded across North America about 1.8 million to 70,000 years ago. Still later around 80 million to 55 million years ago, geologic uplift pushed up the Canadian Rockies, almost like pushing a rug on a hardwood floor forming giant wrinkled mountain chains.

In some places the rocks are jutted up haphazardly and almost violently in serrated ridges festooned with hardy orange lichens. Some of these ridges come from limestone and sedimentary rock formed from shallow seas that once existed here over 300 million years ago! From ancient sea floor to snow capped peaks, wandering over these mountains is to wander through a story written in a foreign and ancient tongue.

Water Towers

Even with my boots on, I give my feet about a minute before they go completely numb in these waters. Backpacking through the Y2Y stream crossings are a common necessity. Some roar past in violent rushing currents and others meander and pool in braided valleys.

These waterways are ephemeral though, changing depending on the season and the snowpack. Snowfall influences everything here, but varies from year to year. Indeed, with a few exceptions, snowpack reconstructions over time show that the northern Rocky Mountains experience large snowpacks when the southern Rockies experience meager ones, and vice versa.

This variability in snowmelt has huge implications not just for the Y2Y ecosystem from year to year but for millions of people downstream whose water supplies are fed by the Colorado, Colombia and Missouri river systems all originating in the Rockies. Since water in the West is reliant and interwoven with mountain's ability to capture moisture-laden clouds and store water in snow, the Rockies are sometimes referred to as "water towers" releasing water to the land from the top down.

Beautiful Deceits

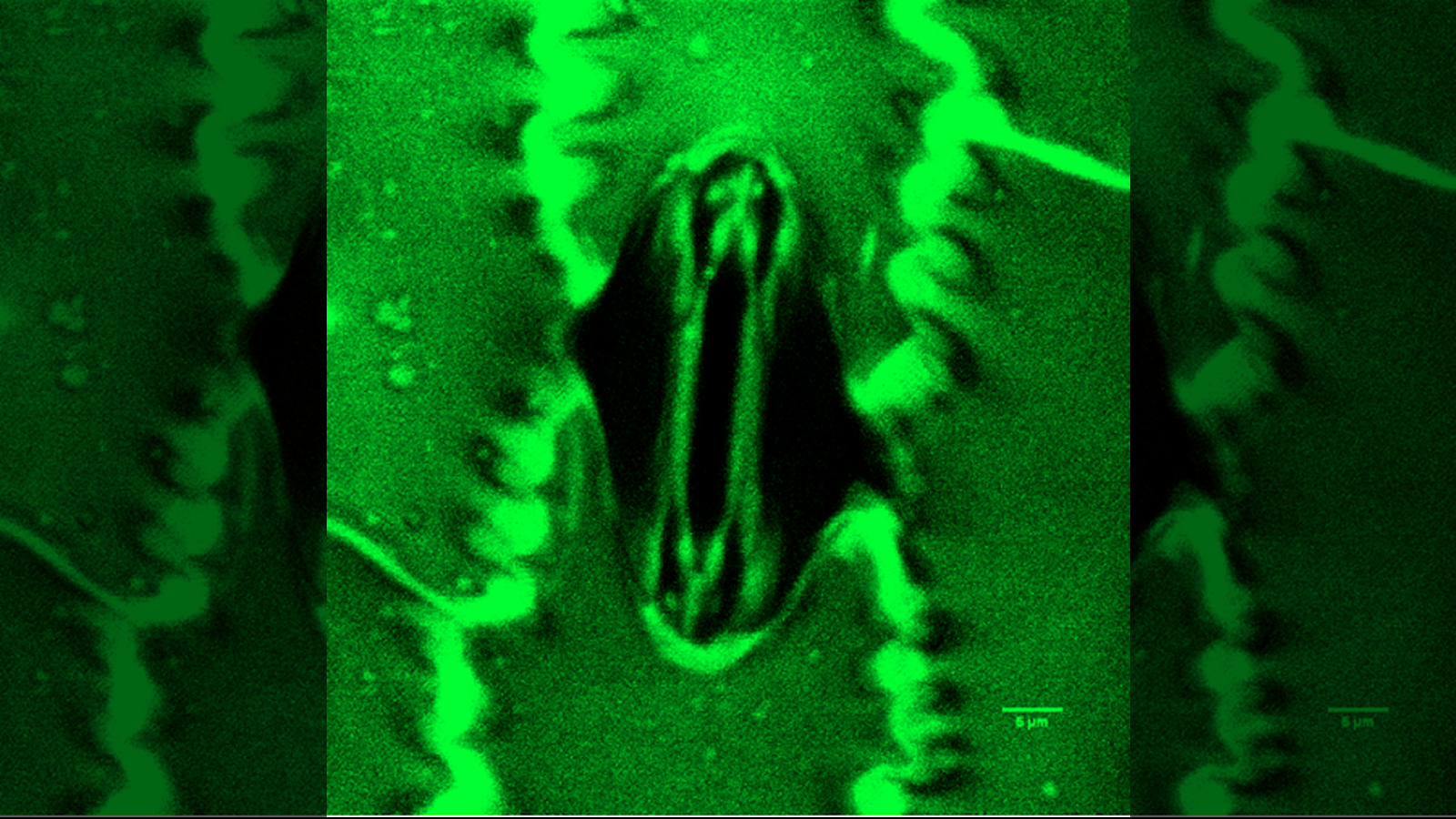

Some days hiking through the Y2Y I find myself looking down more than looking up, searching for treasures like this lady slipper orchid complete with attendant, a perfectly camouflaged crab spider. Any lover of wildflowers will be able to recognize this predicament. During the spring and summer months innumerable blips of color and form radiate from the landscape.

Since the ecosystems of the Rockies vary with topography and latitude, the variety of wildflower species also varies from montane forests to high alpine regions and everything in-between. Some of the most beautiful and bizarre wildflowers are those adapted for the harsh alpine regions above the tree line. [The Most Disgusting and Deadly Flowers]

To survive here wildflowers take on unusual and ingenious evolutionary adaptations. Waxy leaf surfaces retain moisture lost from the winds, hairs guard against harsh UV rays, compact cushion shapes minimize wind exposure, and strong deep roots find limited nutrients. All these adaptations help alpine plants survive and thrive by coaxing beauty out of adversity.

Frightening Truths

Hiking the Y2Y, the imprints of huge muddy paws and steaming dung piles full of berries continually remind me I'm in bear country. Although I know that bear attacks are rare, I whistle and clap my hands passing through dense thickets and hang my food supplies high in tree snags away from camp.

Both black bear and grizzly bear roam the Y2Y wilderness. For the grizzlies this is one of their last refuges in North America and the spine of the Rockies serves as a vital connecting road between their now fragmented populations. An estimated 100,000 grizzly bears once roamed over western North America from Mexico to Canada to the Great Plains.

Today only one percent of North America's remaining grizzlies occupy only two percent of the remaining habitat available in the lower 48. This is almost exclusively in the Y2Y region. By focusing conservation efforts towards connecting those habitats that remain means more could thrive here. Indeed, it is estimated that with proper connectivity between habitats, the Y2Y region could support between 17,000 to 20,000 grizzlies.

Protectors and Stewards

Any visitor to famous national parks like Yellowstone or Banff are often surprised at the masses of people in the summer months, almost loving the wilderness to death! Really though, only a few miles deep into the backcountry the crowds diminish and die off completely. Hiking through a combination of national, state, provincial parks and wilderness areas in the Y2Y, I encountered only a few people, like this backcountry ranger in Montana's Bob Marshall Wilderness. Often I saw no-one else for days. [Top 10 Least Visited National Parks]

Both the beauty and genius of the parks and protected areas that connect the Y2Y region are that they serve multiple needs at multiple levels for wildlife and people. First, and foremost parks like Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park straddling the U.S.- Canada border serve as vital refuges for wildlife species like grizzly, wolf and elk that have since been eliminated in other parts of North America, while engendering cooperation for common cause between people and governments.

Secondly, these wild places are important to many people as integral parts of the ecosystem ourselves. We are drawn to the spectacular scenery and ruggedness of these landscapes. Perhaps lying dormant inside all of us is the hunger to re-engage with our own origins and kinship to the land, which in the modern era so many of us have become alienated from. The protected areas of the Y2Y draw us in to engage to hike, ski, canoe, fish and simply commune with nature.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Connect the Dots

For over an hour I bushwhacked an eroded half-lost trail ever upward. Alder thickets blanket the way and smack me in the face mockingly as I push on, gaining 2,000 feet in elevation. As I stumble out above the tree line onto a bare rocky slope I looked backwards from whence I've come to Alberta's Caste-Crown Wilderness. From here the wilderness looks unending, impossibly vast and inexhaustible. It is hard to believe that this is not so this region is ground zero for conservation.

Despite considerable federal and provincial protection throughout many parts of the Y2Y, many more areas remain outside of protected areas or though protected, sit exposed and vulnerable to shifting political and economic winds. This is the case along Alberta's front range where natural gas exploration drives much of the local economy. Oil wells and compressor stations hover on the edge of these lands, while exploration teams push roads into the wilderness areas that bring in people and human-wildlife conflicts.

These incremental pressures that chip away at the wilderness in small parts and measures are perhaps the greatest overall threat to the integrity of the Y2Y ecoregion. Over time this "chipping away" fragments the Y2Y wilderness, creating significant barriers to dispersal and survival for all number of creatures.

Following the Grizzly Trail

When we saw the isolated speck on the topographic map marked "lost lake" we just had to explore it. Hiking a few miles distant we meandered through larch forests and tiptoed around snow banks freckled with delicate yellow glacier lillies poking through the snowmelt. Though it is mid-July, summer has yet to fully arrive up here, but we braved the icy, still waters for a swim anyway. It took some self-determination to dive in, but for the entire day that cool fresh feeling never left me pure refreshment.

Experiencing the Y2Y intimately by foot, reliant upon my own simple ingenuity and self-reliance is like a pilgrimage. A test to follow the grizzlies' trail the corridors of parks, protected areas and vital habitats that form the sinews of the Y2Y ecoregion. Conservation biologists have found this connectivity is vital in preserving the long-term health of this ecoregion.

It is not good enough just to create protected habitats that are isolated, like islands surrounded by a human-dominated landscape. This is just not how most species have evolved. Their habitats must be connected to other habitats through corridors if they are to be robust and thriving in the long term for wildlife, and human generations to come.

I Heart the Y2Y

Hiking for over a month across parts of Montana, Alberta and British Colombia, I've only just glimpsed a small section of the Y2Y. If I had the time and inclination (and some dough!) I could keep on hiking north along the spine of the Rockies all the way to the Yukon territories. It is enough to make me pause and wonder as I gaze out on a sea of mountains marching off into the distance. In spite of the wild grandeur and immenseness this landscape radiates, it is the small things that I notice most, like tiny wildflowers reaching towards the sun and bright orange jewel lichen oddly grown into the shape of a heart.

The Y2Y region is one of the world's few remaining areas with the geographic and biological diversity to accommodate the wide-ranging adaptive responses that might allow whole plant and animal populations to survive our rapidly changing world. In light of climate change predictions by scientists, safeguarding the ecological integrity and interconnectivity of the Y2Y is our best shot to insure a healthy future for wildlife and people through ongoing public dedication, activity and involvement.

As the most intact mountain ecosystem remaining on Earth, the Y2Y offers some of the best types of resilient landscapes that species and ecological processes will need to survive the coming changes and give hope for a wild future.Read more: Walk Through the Wilderness of the Porcupine Mountains

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus