First Expedition to Probe Deepest Sea Vent on Earth

Eat your heart out, Jules Verne: This week, a ship packed with scientists is setting out for a three-week Caribbean cruise to one of the most extreme and least explored places on Earth. It's a real-life trip that might have been ripped from the pages of the imaginative novelist's fantastical fiction.

The 23 scientists aboard the research vessel Atlantis are embarking on a first-of-its-kind mission; their quarry lies in the perpetual night of the deep ocean, in a mysterious world powered only by the furious heat of the planet's inner workings.

Their destination appears in Google Earth as a shadowy gash in the Earth just south of the Cayman Islands.

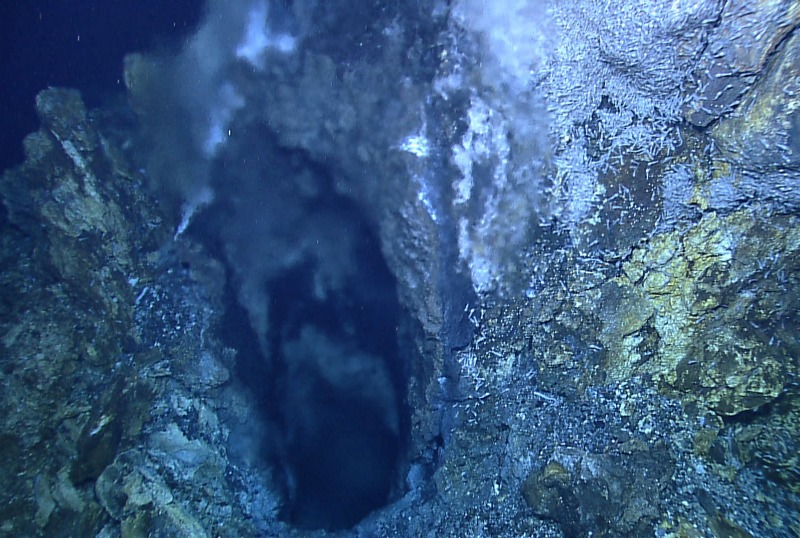

It is the Mid-Cayman spreading ridge, a rift in the seafloor some 70 miles (110 kilometers) long and more than 9 miles (15 km) across, where geologic forces are shoving two tectonic plates apart and birthing new oceanic crust — and fueling what may be two of the most remarkable hydrothermal vent sites on Earth.

Until recently, it was thought that hydrothermal vents — essentially, seafloor chimneys that spew forth a scalding soup of chemically altered seawater — couldn't exist along the Mid-Cayman spreading ridge, also called the Mid-Cayman Rise. It is the deepest spreading ridge on Earth, plunging to nearly 20,000 feet (6,000 meters) in places, and also among the slowest moving, creeping apart at just 0.6 inches (15 millimeters) per year. Scientists thought that, at such a snail's pace, the system lacked the volcanic heat required to sustain a hydrothermal vent.

But in 2009, scientists discovered two.

One vent, the Von Damm, may offer clues to how life first arose on our planet. The other, dubbed the Piccard, lies 16,400 feet (5,000 meters) below the surface — the deepest vent ever discovered on Earth — and may prove to be the hottest. [Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Yet despite the tantalizing possibilities of scientific riches offered by each vent, logistics have prevented scientists from taking direct temperature data and certain specimens from either site — until now.

Into the unknown

This month, with the help of a deep-diving robot, scientists will gather some of the first samples from these oases of strange life on the seafloor.

"We're guaranteed to find dozens of new species — that's a no-brainer," said marine scientist and expedition member Cindy Lee Van Dover, director of the marine laboratory at Duke University's Nicholas School of the Environment.

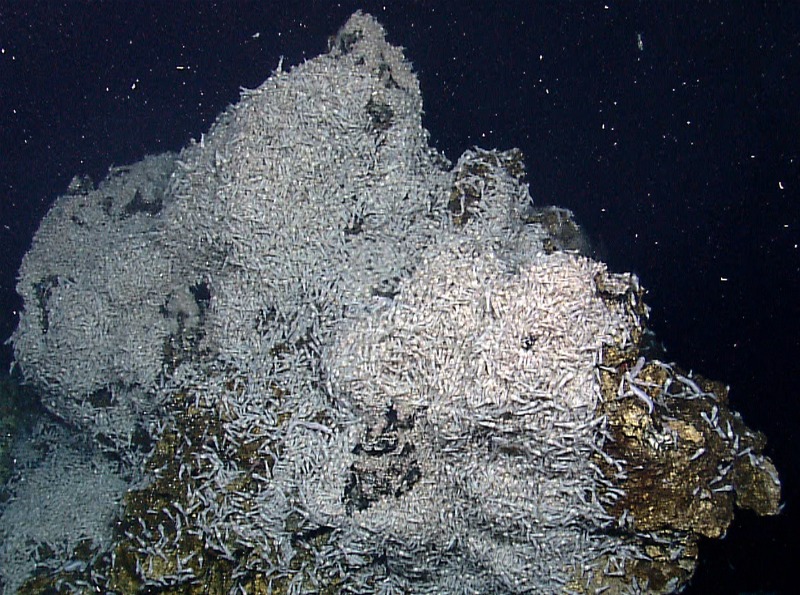

Bizarre menageries of creatures have been discovered living near vents in oceans around the world, from newfound yeti crabs at vents in the Antarctic to large tube worms in the Pacific. The animals survive on the chemical compounds that are formed when seawater interacts with deep, superheated rocks, exposed by fissures and cracks in the seafloor.

An August 2011 expedition filmed tube worms living at the Von Damm vent site — the first ever found at a hydrothermal vent in the Atlantic. [Related: Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures]

"We have to collect specimens to know, but just looking at the pictures it looks like it's something we've never seen before," Van Dover told OurAmazingPlanet. "So we're excited about that."

Van Dover and the other scientists aboard will be able to collect a wide variety of samples — animals, rocks, seawater — with the help of Jason, a remotely operated vehicle with two arms equipped with pincers at the end. "They can be very precise and very gentle," Van Dover said.

To capture a tube worm, she said, the ROV gracefully rotates its metal hands, twirling the long creatures like spaghetti on a fork.

It's … alive?

Beyond the intriguing implications for new species discovery, the Von Damm vent may offer scientists a chance to peer back into the origins of life itself. At 7,500 feet (2,300 meters) deep, it's the shallower of the two vents, yet the rock there is a geological throwback to Earth's early years, a couple billion years ago. The site may be one of the few accessible places on the planet where seawater can interact with heated primordial rocks, producing the kind of warm, hydrogen-rich broth scientists suspect gave rise to the world's first organisms.

"The hydrothermal reactions there are probably our closest modern-day analogue for geology in the first half of Earth's existence," said Chris German, chief scientist on the expedition and a geochemist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts.

That means the Von Damm site could provide a glimpse of the mechanisms that, over the ages, transformed lifeless molecules to living, complex beings.

"If you track [life] down to the lowest denominator — the common ancestor— it speaks to a single-celled organism that thrived in high temperatures and low oxygen environments," German told OurAmazingPlanet. "And deep-sea hydrothermal hot springs fit that bill."

Although previous research indicates Von Damm is a very good candidate for this process, called abiogenesis, temperature is a key factor, German said.

"If it's too hot or it's too cold, it's no good," he said. "There's a Goldilocks zone where it's just right. Somewhere around 200 to 300 degrees Celsius [390 to 540 degrees Fahrenheit] would be the sweet spot."

The answer could be revealed in just a few days.

NASA scientists are also taking part in the expedition's work in hopes that data from the Von Damm vent may offer clues to what geological conditions could set the stage for life on other worlds. Europa, one of Jupiter's moons, is of particular interest, German said.

Deep frontiers

Temperature, along with nearly everything else, is also a big unknown for the Piccard vent.

"It's twice as deep, and less well-known," German said. "With the Piccard site we're going to be making it up as we go along, which is what makes it exciting."

The vent, named for Jacques Piccard, one-half of the only team to ever travel to the deepest spot on the planet's surface, the Mariana Trench, is a whopping 3,000 feet (900 m) deeper than the second runner-up.

And with hydrothermal vents, deeper often means hotter.

"The deeper they are, the higher the pressure, so the higher the temperatures can get to," German said.

"Right now, the temperature record for a hydrothermal vent on the seafloor is about 407 degrees Celsius (465 F). This one could be hotter," said Jill McDermott, a Ph.D. candidate at the MIT-WHOI joint program.

Theoretically, nearly 200 degrees F (100 C) hotter— but there's no guarantee.

And although researchers aren't entirely sure what they'll find at Piccard, comparing the deeper vent with Von Damm is a key part of the mission.

"The really cool thing about these two sites is they're really close to each other, but there's a real difference in depth," German said.

The vents are about 14 miles (23 km) apart, but Piccard is 9,000 feet (2,300 m) deeper than Von Damm.

"One of the things we're very keen on looking at is the gene flow from deep to shallow," Van Dover said. "Depth sometimes seems more important than distance — at least that's a hypothesis we're trying to test."

It could be that species living at vents thousands of miles apart have more in common with one another than those closer together, but at different depths, where the immense pressure could affect what animals can survive there.

Where there are shared species, Van Dover said, researchers can hunt through specimens' DNA for genetic markers that indicate family ties — near-relations, distant cousins, to utterly alien — from vent to vent and, with samples gathered from far-flung vent sites, from ocean to ocean.

Eventually, such research could allow scientists to construct an evolutionary map of genetic alliances across the world's oceans.

"We have a code of conduct, and we only take as many samples as we need," Van Dover said. On this mission, that means they will likely collect only two or three tube worms, many dozens of shrimp, but far more of the tiniest animals they find at the vents.

"We try to disturb these communities as little as possible," she said.

As for the community of humans aboard the ship, the disturbances are likely to be largely pleasant ones, particularly when the hydrothermal vents first appear on the ship's video screens.

"Everybody is going to be very, very excited," McDermott said. "We've been waiting a long time to see this."

"There's always a shout when we get to the bottom," Van Dover said. "This is the gem. The plum to sample. It's just taken a long time to get here."

The Mid-Cayman expedition is funded jointly by the National Science Foundation and NASA.

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain.Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.