30 Years Later: Eruption of Mexico's El Chichón

Thirty years ago this week, the seemingly dormant El Chichón in Chiapas, Mexico, erupted unexpectedly and spectacularly, wiping out nine villages and killing an estimated 1,900 people.

The volcano had been slumbering for nearly 600 years, but in 1982, it erupted three times in less than a week, on March 29, April 3 and April 4. It is the largest volcanic disaster in modern Mexican history.

El Chichón is a lava dome complex that was heavily forested before the eruption, but the landscape was wiped out for about 5 miles (8 kilometers) around by ash falls, fires and superheated flood waters, according to a NASA statement. The flood waters were the result of a dam that was breached on a nearby river because of the eruption.

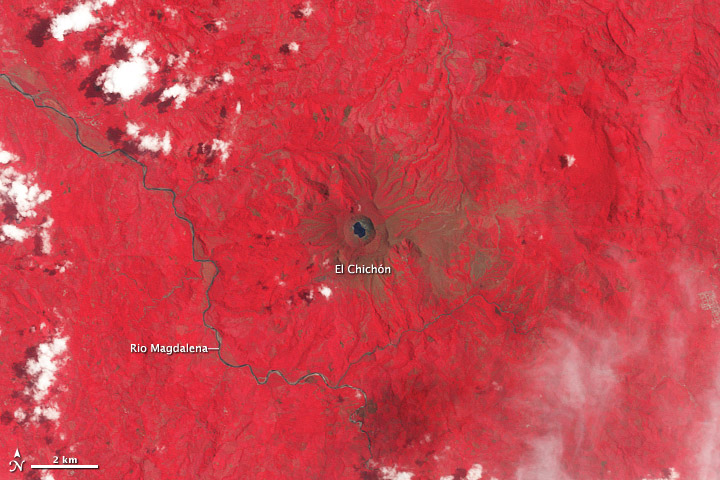

Landsat satellite images of the complex taken on March 11, 1986, and June 4, 2011, show the devastation wrought by the eruption and the recovery that has happened since. In the images, vegetation is red, bare rock and volcanic debris are gray and tan, and water is blue or black. The large amount of gray and tan in the 1986 images shows the extent of the damage to the surrounding region, as well as the new caldera situated in the old caldera and the new, acidic crater lake. The new crater is about 1 km (0.6 miles) wide and 300 meters (980 feet) deep, according to the Smithsonian Institution's Global Volcanism Program.

By 2011, the satellite image shows that vegetation has reclaimed much of the landscape, but gray ash and debris still hugs the shorelines of the river, the crater lake, and the summit.

The impact of the eruptions extended beyond the immediate surrounding though, as they spewed large amounts of sulfur dioxide and aerosols into the atmosphere near the equator, climbing as high as 17 miles (27 km) into the atmosphere. Scientists estimate that the volcanic emissions warmed the stratosphere by about 7.2 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius) and cooled the Northern Hemisphere by 0.72 F (0.4 C), according to NASA. The eruption literally darkened the skies, reducing the transmission of sunlight to Earth's surface. By comparison, the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo lowered global temperatures by 1 degree Fahrenheit (0.5 degree Celsius) over the year after it's eruption.

The total eruption released about the same amount of as the much more well-known eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980, said Erik Klemetti, author of Wired's Eruptions blog and an assistant professor of geosciences at Denison University in Ohio.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.