Man-made Quakes Increasing, But May Not Pose Threat

SAN DIEGO — Human activity is likely causing a dramatic increase in the number of earthquakes striking around the United States, scientists have found, but they aren't sounding the alarm yet. That was the message from researchers gathered here this week for the annual meeting of the Seismological Society of America (SSA).

A broad survey of earthquake activity in the eastern United States from 1970 to 2011 revealed a sharp uptick in the number of earthquakes beginning in 2009. In 2010, the numbers continued to climb, and by 2011, the rate was six times higher than quake numbers for the 20th century.

What was responsible for this sudden increase? Probably the oil and gas industry, scientists said — however, it's not what the industry is taking out of the ground, but what they're putting into it that's triggering the rise in seismic activity.

"It appears likely that these extra earthquakes are related to the disposal of waste fluids," said William Ellsworth, a geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey and one of the scientists behind the large-scale assessment. [13 Crazy Earthquake Facts]

Geological garbage dump

The fluids — mostly brine, a by-product of oil and gas extraction — are injected about a mile underground to sequester the extremely salty liquid away from drinking water, or to force oil deposits to more accessible areas.

Scientists emphasized that deep fluid injection is not the same thing as fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, a technique used to retrieve natural gas from deep rocks.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

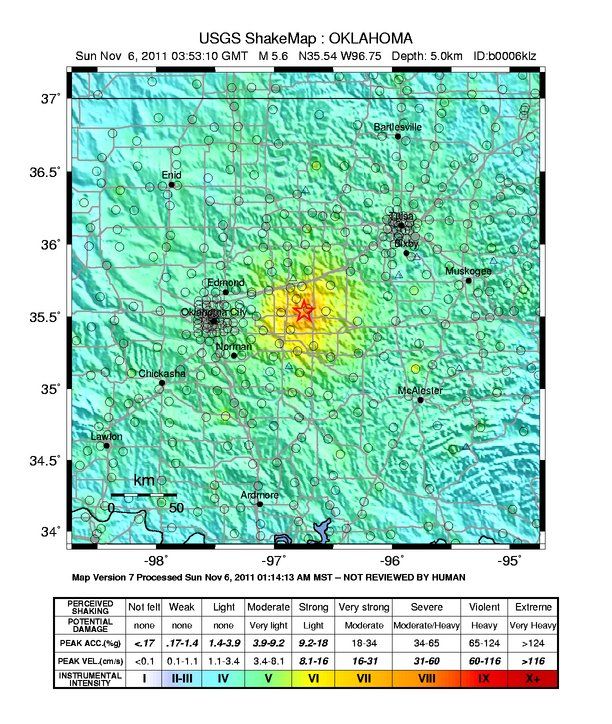

There are roughly 144,000 fluid injection wells around the country, with the lion's share in Texas, California, Kansas and Oklahoma. In November, Oklahoma was the site of a 5.6-magnitude earthquake that research presented at the SSA meeting has linked to injection wells.

"Damage occurred 84 miles away," said Steve Horton, a research scientist at the University of Memphis's Center for Earthquake Research and Information and the author of the study that found that the quake — the largest recorded in Oklahoma history — and fluid injection wells could be correlated.

The quake, which struck on Nov. 5, 2011, sent crockery crashing from kitchen shelves, damaged a local highway and destroyed 14 homes.

Ellsworth said the newly unveiled research on the Oklahoma quake, with which he was not involved, "is new information. It's a very significant study in terms of the quality of the work they've done," he told OurAmazingPlanet.

However, Ellsworth said, the earthquakes triggered by fluid injection wells, typically around magnitude-3, have been largely benign.

"The earthquakes were by and large small, and while they could be felt by people, few if any were large enough to do any damage — so they don't represent a major seismic hazard," he said.

Jerky history

Since the construction of the Hoover Dam set off small earthquakes in the first half of the 20th century, researchers have known that human activity can trigger earthquakes.

The most infamous example of human construction setting off geological upheaval is a reservoir in Koyna, India. It caused a magnitude 6.3 earthquake in 1967 that killed 177 people, injured 2,000 and left more than 50,000 people homeless. It has been causing earthquakes ever since.

In the case of reservoir- and dam-induced quakes, water percolates down through cracks in the Earth to faults deep beneath the vast lakes. Once connected by these avenues of water, the pressure of all that water above can cause a fault below to rupture.

Although the mechanism is slightly different, water is still the likely culprit in fluid injection-induced quakes. Water introduced to the deep subsurface finds a way to trickle down into faults that would otherwise stay locked together, rocky wall against rocky wall. The water gradually wedges the fault walls apart, and, freed from their stiff embrace, the rock walls suddenly lurch sideways — and, presto — an earthquake.

No threat

Fluid injection wells have been operating around the United States for years, and it's not clear what has sparked the sudden increase in the earthquakes.

Some of the wells are new, but that doesn't explain all the quakes. "One possibility is that we're injecting more waste water in some wells than we were before," Ellsworth said.

Details of what goes on at injection wells — the volume and rate of material injected, fluid pressure and other factors that could affect seismic activity — aren't well-tracked, nor is what sparse data are gathered readily available to scientists. Ellsworth said that better monitoring would be a good thing.

However, he said, very few wells appear to spark earthquakes. "It's a small number of the wells. It's certainly less than one well in 100."

As for the November 2011 Oklahoma earthquake that may be linked to injection wells, "a magnitude 5.6 earthquake has really very limited potential to do damage," Ellsworth said.

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.