Why the Recent Sumatra Quake Was So Strange

The unexpectedly large earthquake that hit Sumatra last month is forcing scientists to rethink common assumptions about earthquake physics, researchers say.

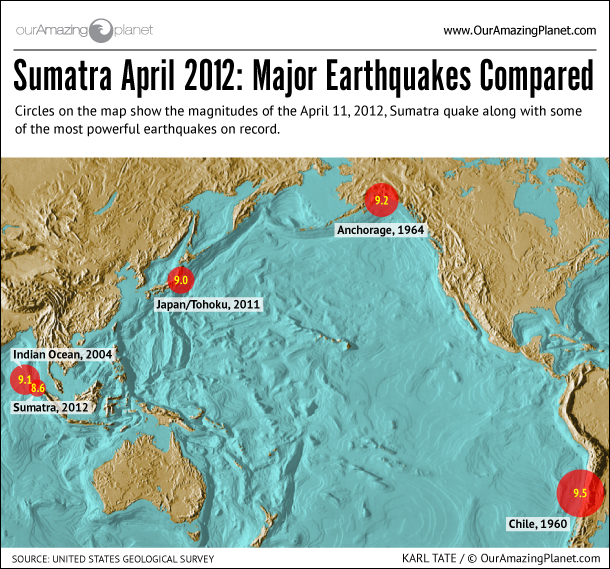

The magnitude 8.6 earthquake that struck in the Indian Oceanoff the western coast of Sumatra on April 11was one of the 10 largest earthquakesever recorded, and was felt as far away as Bangladesh and India. However, no quake-related fatalities were reported.

Seismologists have done preliminary studies on the earthquake and found that it had some unusual aspects, ones that could help them better understand earthquakes that happen away from the boundaries between tectonic plates and better appreciate how powerful those quakes could potentially be.

Odd earthquake

Unusually, this quake apparently occurred in the middle of an oceanic plate. All the other top 10 quakes happened at subduction zones, where one of the tectonic plates making up the Earth's surface is diving beneath another. [13 Crazy Earthquake Facts]

Also oddly, the Sumatra temblor was a strike-slip earthquake, where two parts of Earth's crust slide past each other. Strike-slip quakes are not typically so powerful — the Sumatra event was "far and away the largest strike-slip earthquake ever recorded," said researcher Gregory Beroza, a seismologist at Stanford University. Its magnitude 8.2 aftershock was also among the largest recorded strike-slip earthquakes.

The reason why this quake was surprisingly powerful might lie in how deep the faults that triggered it ran, scientists now suggest.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Seismology readings suggest the Sumatra quake and its aftershock originated at depths between 25 to 33 miles (40 to 54 kilometers). At those depths, rock is blazingly hot, about 1,110 to 1,470 degrees Fahrenheit (600 to 800 degrees Celsius). At such temperatures, rock can become viscous at certain points, and in extreme cases, fault zones may even melt, enabling large amounts of energy to be released as parts of the Earth slide past each other.

Mid-plate quakes

Although the Sumatra quake is the only time a temblor in the middle of an oceanic plate was powerful enough to make the top 10 largest known earthquakes, major earthquakes do regularly occur in the middle of oceanic plates.

"Oceanic plates cover the majority of the earth, and a lot of magnitude 8 earthquakes have occurred within the interiors of oceanic plates in the last few years," said researcher Jeffrey McGuire, a seismologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. "So while the probabilities are extremely low in any one spot, essentially the majority of the Earth's surface can experience a magnitude 8 earthquake."

Still, large earthquakes in the middle of ocean plates likely do not pose much hazard to life or property, since they are well away from populated areas. They also usually only generate small tsunamis, although "there is always a chance that they might set off a submarine landslide — such landslides have the potential to generate large tsunamis," Beroza said.

However, these mid-ocean quakes could shed light on the potential power that quakes in the middle of continental platescan achieve.

"The very largest earthquakes that a fault system or plate boundary is capable of might be larger than was previously appreciated," Beroza told OurAmazingPlanet. "That's not to say this is necessarily normal behavior, but it has to be considered as possible."

Understanding earthquakes that occur within the interior of oceanic plates is challenging "because we do not have long-term monitoring networks on the seafloor," McGuiretold OurAmazingPlanet. "I think one future direction that will be very interesting is that the National Science Foundation's Cascadia Initiative is in the midst of a multiyear monitoring effort of the Juan de Fuca and Gorda plates, which have significant internal strain. This initiative has the chance to capture a moderate intra-plate earthquake with nearby instruments which might really help us understand the processes that lead to the magnitude 8s that have occurred in more remote locations."

McGuire and Beroza detailed their findings online May 10 in the journal Science.