Quakes Along Section of San Andreas More Frequent Than Thought

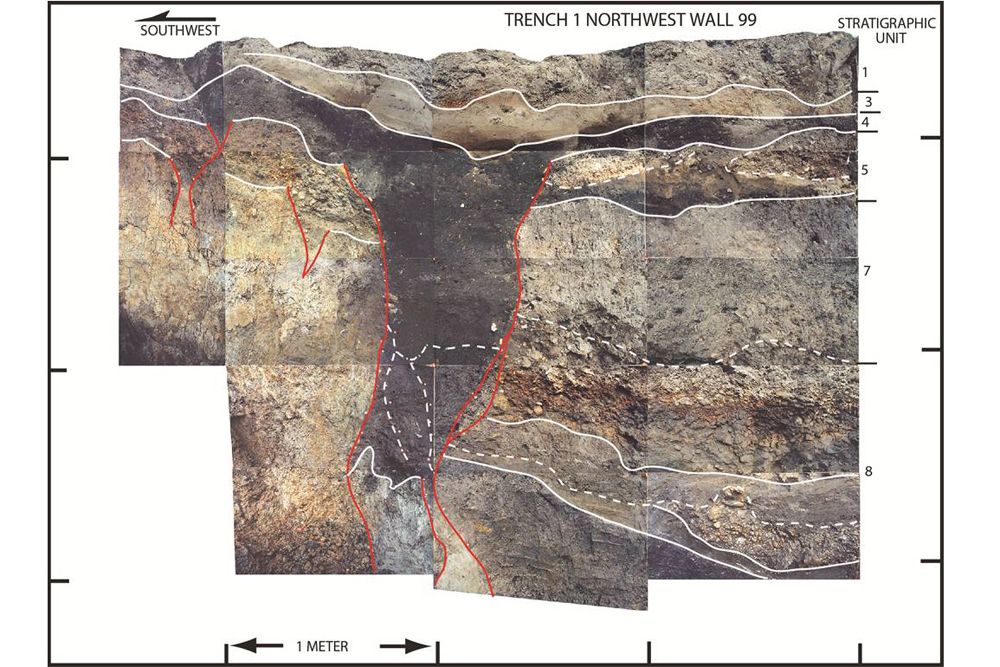

Contorted layers of clay and gravel show a segment of the San Andreas Fault that devastated San Francisco with a huge earthquake in 1906 may be more hazardous than previously thought.

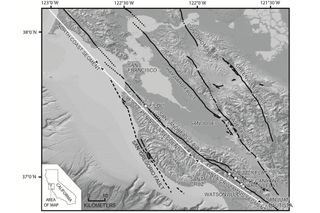

The San Andreas Fault divides California for more than 800 miles (1,300 kilometers) from Cape Mendocino to the Salton Sea. The fault marks the boundary between two plates of the Earth's crust: the Pacific Plate on the west side of the fault is sliding slowly northwest past the North American plate on the east.

Geologists Thomas Fumal and Timothy Dawson dug trenches across the San Andreas Fault in the Santa Cruz Mountains, about 5 miles (8 km) northwest of Watsonville and discovered traces of four large past earthquakes. Broken sediment revealed quakes occur more often than prior estimates, and two historic earthquakes reached further south than found before.

Big earthquakes more common?

In the trenches, Dawson and Fumal found a clear record of the great San Francisco quake of 1906. The three additional earthquakes hit in 1522, 1686 and either 1748 or 1838, give or take a few decades, which means this segment of the San Andreas Fault averages a big shaker every 125 years. That's twice as often as estimates calculated by the Working Group On California Earthquake Probabilities, the group responsible for official earthquake forecasts.

But the uptick in earthquake frequency is unlikely to significantly increase the seismic hazard for the Bay Area, Dawson told OurAmazingPlanet.com. "All types of data feed into the seismic hazard model, and the results of our study are just one type of data," Dawson said, an engineering geologist with the California Geological Survey and member of the earthquake forecast group. "It's kind of like cooking. Adding salt may not radically change the taste of a dish, it just adds to the complexity."

A new seismic hazard model, which includes their research, will be released in early 2013, Dawson said. "Then we will know whether it has affected the seismic hazard in this region," he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Where more risk could come in

However, for Dawson, the discrepancy in frequency is a tantalizing hint to the San Andreas Fault's typical behavior. If only the short Santa Cruz Mountains section shakes every 125 years, then the region's quakes would be smaller, but still quite destructive, like the 6.9-magnitude Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989.

But what if the 7.8-magnitude 1906 quake, which ruptured a much longer length (including the Santa Cruz Mountains), is more typical? "Any new data is important to our understanding of how the fault behaves," Dawson said. "We are really living in a data-poor world in our understanding of how often these large earthquakes occur."

One new clue to the fault's behavior lies in the trenches, where Dawson found evidence of an 1838 earthquake. Known from diaries and mission records to have severely shaken the San Francisco peninsula, geologists hope to pin down the quake's rupture length because it will tell them the magnitude. [13 Crazy Earthquake Facts]

Radiocarbon dating put the year at either around 1748 or 1838, so Dawson sought out other evidence. A wide, quake-caused fissure was filled with pollen grains from the weed Redstem filaree (Erodium cicutarium), introduced by Spanish settlers in the 1800s, as well as an iron nail from the property's first fence, built in 1854. "This study is perhaps the first direct evidence that 1838 ruptured the Santa Cruz Mountains," Dawson said.

If the earthquake ruptured as far away as the Santa Cruz Mountains, it could point to an increased seismic risk in the area.

But geologist David Schwartz, who has worked at a nearby site and visited Fumal and Dawson's trench, believes the evidence isn't yet strong enough to conclude the 1838 quake tore through the Santa Cruz Mountains.

"This is a solid study, it's state-of-the-art and it presents alternative interpretations of issues," said Schwartz, a senior geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, Calif. "One of the real questions we have is where was 1838, and how large was it. It's up to us as a community to develop more data and decide which of these interpretations is actually the right one."

Dawson said he will begin work this summer on two new trench sites to look for further evidence of the 1838 quake in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Dawson and Fumal's research was published in the June 2012 issue of the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. Thomas Fumal died in 2010.

Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.