9 Craziest Ocean Voyages

Crazy sailing

Humans have been exploring the sea for thousands of years. In primitive rafts and leaky sailing ships, our ancestors faced down waves, wind and ice, often with no guarantee that they'd ever see land again.

While all of these voyages carried their fair share of peril, some were more ambitious ? and dangerous ? than others. Here, OurAmazingPlanet looks at some of the craziest sailing expeditions ever taken.

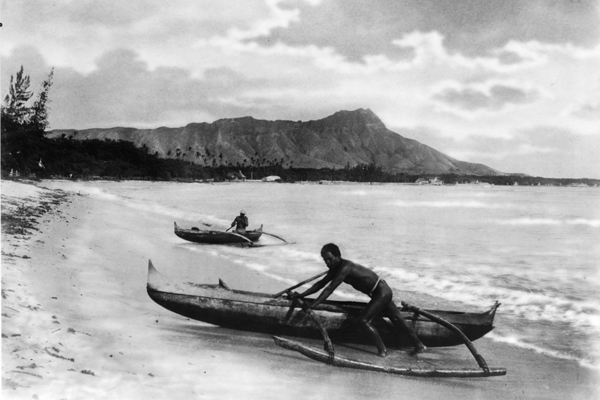

The Pacific migration

Hundreds of thousands of years ago, our first ancestors took to the sea on wooden rafts and in dugout canoes. Little is known about these first ocean explorers. They may not have even been Homo sapiens: Research presented in January 2010 at the American Institute of Archaeology annual meeting suggested that human ancestors like Homo erectus may have sailed the Mediterranean at least 130,000 years ago.

By 50,000 years ago, humans had sailed to Australia and were beginning to spread out across the Pacific. According to Te Ara, an online resource of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage, these primitive mariners began riskier journeys around 1200 B.C., colonizing the remote atolls and isles of Polynesia. They may have made it farther than that: A 2007 analysis of fossil chicken bones, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggested that Polynesian sailors reached the shores of Chile by the 1300s at least 100 years before the Spaniards "discovered" South America.

Leif Ericson discovers North America

While the Polynesians were exploring the South Pacific, Vikings roamed the North Atlantic. According to the Saga of Erik the Red, explorer Leif Ericson set his course for the west around the year 1000, chasing rumors that there was land west of Greenland.

Fortunately for Ericson and his 35-man crew, the rumors were true. The sailors landed on a rocky stretch of coast now thought to be Labrador. Unimpressed with the bare land, the crew pushed on, landing a second time on sandy beaches in what may have been Newfoundland. The third time proved a charm for Ericson and his men; they landed again at a place they called Vinland, where the salmon were plentiful and grapes grew wild.

Despite the bounty, Ericson and his men stayed only one winter and then returned to Greenland loaded down with timber. The Vikings made a few return voyages to North America, but clashes with "skraelings" (the Norse word for the natives of Vinland) prevented permanent settlement.

Zheng He's Southeast Asia expeditions

Captured and castrated by Ming Dynasty soldiers in the late 1300s, Zheng He rose from court eunuch to commander of the Chinese Navy. His reign was the golden era of Chinese sea exploration.

Zheng He's first voyage, in 1405, took him and his fleet of giant "treasure ships" to Southeast Asia, where they traded and demanded tribute for the Chinese court. At up to 400 feet (122 meters) long, Zheng He's ships made Christopher Columbus' 90-foot (27 meters) Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria look like bath toys.

Over the next 28 years, Zheng He launched six more expeditions, each with hundreds of ships and up to 28,000 crewmen. He travelled as far as East Africa, returning to China loaded down with spices, ivory and even giraffes.

Christopher Columbus' fourth New World voyage

In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue and found a side of the world that his contemporaries in Europe didn't know existed. But it was his fourth and final voyage that almost did him in.

In 1502, the aging explorer sailed from Spain to the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. He wasn't welcome; despite his pleas and warnings of an impending hurricane, the island's governor refused him port. Columbus took his fleet of four rickety ships around the island to weather the storm. Meanwhile, the governor unknowingly sent a fleet of 30 treasure ships directly into the gale. Only one made it to Spain.

All four of Columbus' ships survived, but the sailors' trials weren't over. Shipworms ? clams that eat away at wood ? plagued the fleet. One ship had to be abandoned. Another sunk. The men piled into the two remaining vessels and ran aground on Jamaica, where they would live among increasingly hostile natives for more than a year before finally securing rescue.

Magellan circumnavigates the globe

Ferdinand Magellan left Spain in 1519 with five ships and 277 men, hoping to blaze a western route to India in service of the spice trade.

Storms forced the fleet to winter in Patagonia, where mutiny broke out. Magellan beheaded a ringleader. A storm destroyed one ship; another ship either mutinied or sank. In November, the remaining three ships pushed into the Pacific, where they would go weeks without sighting land. Provisions ran scarce and scurvy crippled the crew.

Eventually, the sailors reached the Philippines, where Magellan decided to perform a little extracurricular evangelism. When one chief resisted, Magellan attempted to clinch the conversion by force. A battled ensued, and Magellan was killed. By the time the fleet limped back into Spanish waters, three years had passed and all but 18 of the original crew were dead.

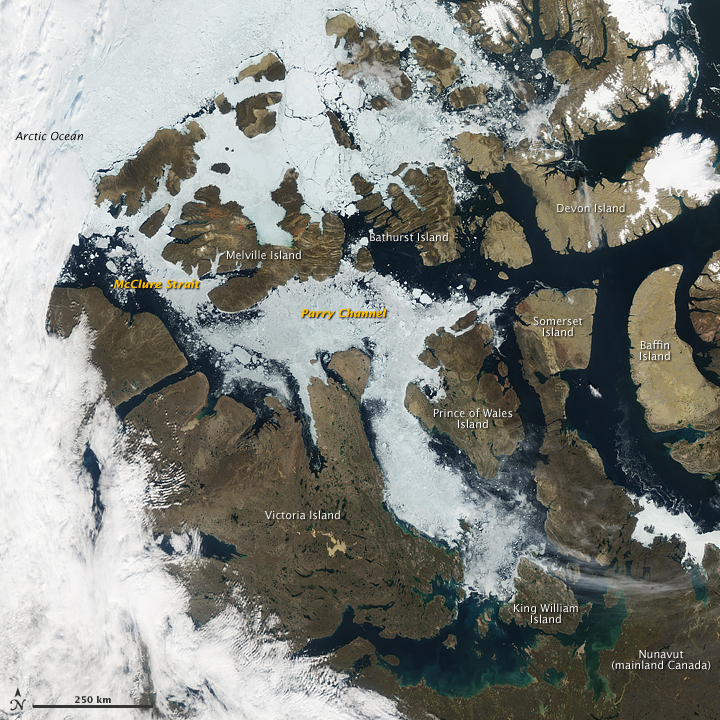

James Cook's search for the Northwest Passage

British explorer James Cook made his name exploring the Pacific, mapping the coastline of New Zealand, and circumnavigating the globe in 1768. In 1776, however, Cook was on a mission to find a sea route through the Arctic the fabled Northwest Passage.

Cook and his crew sailed up the western coast of what is now Canada, but ice made any attempt to traverse the Arctic futile. Nonetheless, Cook managed to produce the first maps of the west coast of North America.

The ships returned south, landing in Hawaii. The island's inhabitants, who may have seen the ships' arrival during a religious ceremony as a sign that the sailors were gods, warmly welcomed Cook's men. But the mood turned sour a few days later when a broken mast sent Cook's fleet back to Hawaii for repairs. A skirmish over a stolen boat turned deadly, and the islanders stabbed Cook to death on the beach.

The voyage of the Hunley

In the waning days of the American Civil War, eight Confederate soldiers submerged themselves in the Atlantic in a 40-foot-long (12 m) iron tube and set out to blow up a Union ship.

The tube was the Hunley, the world's first operational submarine. It was a dangerous piece of equipment: Even before it saw combat, the Hunley sank twice, taking 13 lives. The Confederate military raised it both times.

On the night of Feb. 17, 1864, the Hunley made her move, embedding a torpedo in the USS Housatonic and sinking the massive warship in mere minutes. Fortunately for the sailors on the Housatonic, the ship was anchored in shallow water. Only five Union soldiers died; the rest perched on the rigging, waiting for rescue.

The crew of the Hunley wasn't so lucky. The submarine never returned from its mission. In 2000, 136 years later, archeologists raised the Hunley from the sea. The remains of its eight crewmembers were still inside.

Ernest Shackleton and the voyage of tne Endurance

In December 1914, the ship Endurance set sail carrying explorer Ernest Shackleton and a 27-man crew. The goal was to anchor off Antarctica and complete the first crossing of the continent.

But the Endurance would never reach Antarctica proper. After weeks of battering through the ice floes of the Wedell Sea, the Endurance was trapped by the ice pack.

The crew hunkered down in the suspended ship for the winter, but it was only a matter of time before the spring ice breakup crushed the Endurance like balsa wood. On Nov. 21, 1915, the Endurance sank beneath the sea.

Shackleton and his men spent the next months camped on the ice, surviving on penguins, seals and their own sled dogs. In April, they set off on another grueling ocean voyage, this time in lifeboats salvaged from the Endurance. Racing their way through floating ice, the men faced storms, seasickness and passing killer whales before managing to land on nearby Elephant Island. From there, Shackleton and five men launched an 800-mile (1,300 km) lifeboat journey to the island of South Georgia to find a rescue ship.

Twenty-two months after the Endurance first set sail, Shackleton returned to Elephant Island to rescue his men. Miraculously, the entire crew survived.

Roz Savage rows the Pacific

In 2005, Roz Savage became the first woman to row solo across the Atlantic Ocean. In 2007, she set out to repeat the accomplishment on the Pacific.

The journey had to be aborted after Savage's rowboat capsized three times in 24 hours. In 2008, she tried again, fighting strong winds from California to Hawaii. A few weeks in, her water filtration system rusted out. Fortunately, she ran into a ship full of environmental activists, who helped replenish her water supplies.

Savage hit trouble again on the second leg of her journey in 2009. The winds were against her, and provisions ran short, forcing her to change her goal from the South Pacific isle of Tuvalu to nearby Kiribati. From there, Savage made one more 45-day push to Papua New Guinea. On June 3, 2010, after 249 total days at sea, Savage became the first woman to row solo across the Pacific Ocean.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.