Weird Moth Genitals Reveal 3 New Species

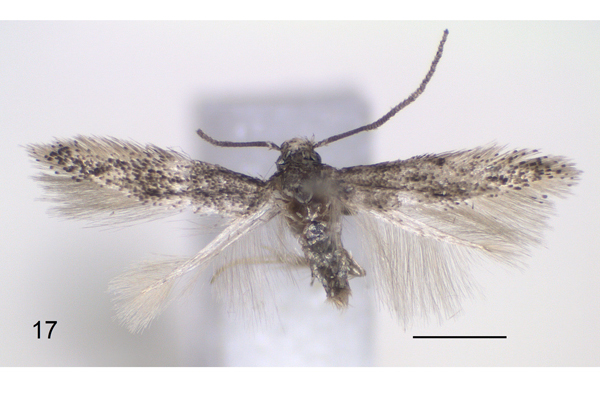

Three new species of "micro" moths have been identified in South Africa's Tswaing Reserve through, in part, a thorough exam of the their genitalia.

Insect species, and even species from other animal groups, can look remarkably similar, making it tricky to accurately identify separate species. This means that scientists have to look for sometimes-minute differences.

Especially when looking at moths with wingspans no bigger than a few millimeters with similar wing patterns, insect genitalia are "the best indicator to diagnose a species," said Jurate de Prins, of Belgium's Royal Museum for Central Africa and the discoverer of the new species.

De Prins also uses more modern methods like DNA barcoding, but moth genitalia can be so varied that sometimes a quick check down there is all it takes to verify a new species. [Images: New Moth Species' Genitalia ]

Leaf miner moths

The three newly identified moths are part of the Urodeta genus, a group of moths that has not been very well-studied. What is known is that they are leaf miners — a type of moth whose larvae hollow out chambers inside leaves.

"They don't eat the leaves, but they live inside. This evolutionary adaptation is really unique," de Prins told OurAmazingPlanet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Typically, de Prins said, she and her team collect moth larvae from the wild, looking for damaged leaves on trees and bushes, and rear them to adulthood under laboratory conditions. But with Urodeta, nobody knows which plants the larvae live in.

"It's very hard to find [an Urodeta mine] the size of 2 millimeters (0.07 inches) in the savanna," she said. So instead, de Prins brought a car battery to the nature preserve, which is near Pretoria, and powered an ultraviolet light to attract adult moths. "I am standing half the night, or even the whole night," she said.

The trick worked: The moths, drawn by the light, landed on a screen de Prins had set up. Then she trapped them in tiny boxes to bring them to the lab.

It was there that she mounted the insects and prepared microscope slides of the tiny insects’ genitalia, staining them with dye to make them more visible. This also makes them look, to the untrained eye, like bizarre flowers or alien creatures. Some male species have "hooks and grasps and spines and claspers" on their reproductive organs, said Chris Grinter, an entomologist at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

Lock and key

The differences in the insects' private parts allows scientists to distinguish between species as well as match up males with females, as their bits often fit together like "lock and key," de Prins said.

Some males are willing to mate with just about anything, Grinter added, so matching genital shapes are actually an important adaptation.

As forUrodetamoths, they may not be the flashiest, but studying them is an important part of documenting the biodiversity of sub-Saharan Africa, de Prins said.

"I firmly believe that in 200 years, people will come to the museum and say, 'Aha. That's what Urodeta looked like,'" she said.

Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Rachel is a writer and editor based in Washington, D.C., who covers a range of topics for Live Science, from animals and global warming to technology and human behavior. Rachel also contributes to National Geographic News, Smithsonian Magazine and Scientific American, and she is currently a senior editor at Next City, a national urban affairs magazine. She has an English degree with a journalism concentration from Adelphi University in New York.